Although the quote “You can’t know where you’re going if you don’t know where you’ve been” was not written about the wild turkey, it could have been. And there is, perhaps, no one more qualified to know what lies ahead for America’s grandest gamebird than the person who has devoted his life to ensuring its future.

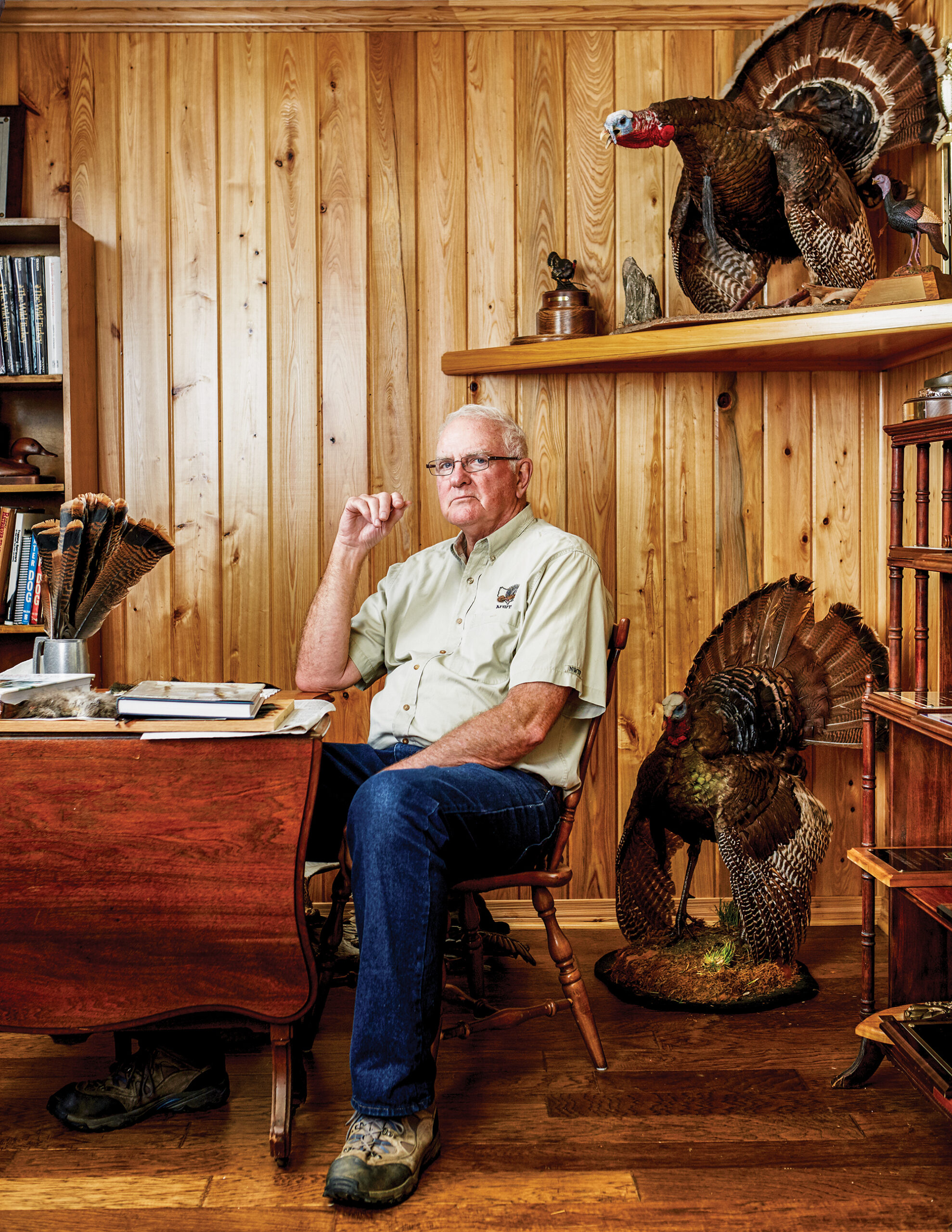

Both as a hunter and as a wildlife biologist, Dr. James Dickson was well in the forefront of turkey research during the golden era of restoration—the 1970s to the 1990s. But even before that, he had lost a small piece of his soul to the American bird.

“I was born a hunter,” Dickson says. A scholarship at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee, following a boyhood spent hunting small game, provided a life-changing epiphany. One of his duties was to keep Sewanee’s Forestry Library open during evenings, and there he discovered Roger Latham’s Complete Book of the Wild Turkey. He read and re-read it, all the while thinking, “Wouldn’t it be great to just hear a gobble or, better still, see a wild turkey?”

Dickson, now 73, went on to be not just a wildlife biologist with a high level of expertise, but someone who savors every sunrise of spring turkey season. He is also a man well worth heeding when it comes to thoughts on the sport’s status today along with what the future holds for America’s big-game bird. Dickson abetted their meteoric rise and has remarkable insight into the current day’s challenges.

EARLY GOBBLING

More than 60 years have passed since a 1948 agreement between the United States Forest Service and the South Carolina Wildlife Resources Department launched trapping and relocation of wild turkeys in the Carolina Low Country. And over the ensuing decades, the program has successfully helped restore the birds nationally. The emergence of the National Wild Turkey Federation (NWTF) in the early 1970s facilitated and expedited the process through provision of transport boxes and the creation of a Technical Committee, which provided input on other relocation sites. The end result of these interacting forces was, early in the 21st century, the completion of one of the greatest of all wildlife restoration success stories, putting turkey populations at an all-time high.

Along with Tom Rodgers, the NWTF’s visionary founder, and Dr. Lovett Williams, a Florida-based biologist whose endeavors bridged the yawning divide between science and the ordinary hunter, Dickson was on the front line of these efforts. Now retired, he spent more than two decades as a research biologist with the U.S. Forest Service before becoming Louisiana Tech University’s Merritt Professor of Forestry. He was always intimately involved in all things turkey.That included multiple terms on NWTF’s board and writing dozens of research papers on wild turkeys. Dickson was a primary contributor to the landmark book Wildlife of Southern Forests, and edited one of the most impressive turkey studies ever, The Wild Turkey: Biology & Management, published in 1998.

We know what has happened, but lingering questions remain about why restoration worked so well and where we are headed. Dickson’s primary concern is about declining turkey numbers, notably in the Southeast, over the last decade or so. Overall, wild-turkey population estimates are between 6 million and 6.2 million birds—down from a record high of 6.7 million. The decline in Alabama has been estimated at 20 percent since 2010. In Georgia, birds are down 25 percent since the 1990s. In South Carolina, the 2015 harvest was down 40 percent since the 2002 record season.

Turning around the population drop, according to Dickson, lies in research.

CAUSE AND EFFECT

“Wildlife populations probably wax and wane much more than we realize,” he says, stressing that turkey population viability focuses on productivity factors such as hen breeding and nesting success, and poult survival. It could well be that population declines are merely part of a natural cycle rather than a result of predation, disease, or other factors. “Often new populations fare well initially but lose some viability over a certain period of time,” he says.

While there’s no question in Dickson’s mind that habitat loss depresses turkey population numbers, he notes that in places like New England, turkeys have shown remarkable adaptability, even thriving in the suburbs. Another part of the habitat conundrum Dickson describes as an “inverse relationship between land management efficiency and wildlife habitat.” Among the negatives he lists in this regard are farmers eking out everything possible from their fields, vast expansion in field size, ruthlessly efficient harvesting techniques, and widespread herbicide use. Add commercial forests grown on short rotations, prolonged drought in some regions, reduction in habitat diversity, and what he interestingly calls a “loss of fire,” and the result is forces, both natural and man-induced, creating vast areas with little cover for feeding and nesting.

While some critics point to these dynamics as indication of the ineffectiveness of the NWTF, Dickson draws the opposite conclusion, saying the conservation group is more vital than ever. Becky Humphries, the NWTF’s chief conservation operations officer, says, “We need to continue to promote and protect turkey populations and habitat,” says Humphries, “and through the Technical Committee all of us can join hands for optimum habitat management.”

The NWTF has just completed a strategic vision document that heralds the wild turkey’s comeback even as it calls for refocusing of the vision going forward. That will involve ongoing coordination of research efforts between state and federal agencies, recognizing and evaluating the effects of habitat changes, and improving hunter access, all the while maintaining respect for the sport’s heritage.

THE ROAD AHEAD

The goal of the NWTF’s 10-year initiative, “Save the Habitat. Save the Hunt,” is ambitious, according to CEO George Thornton.

“The objective is to conserve or enhance 4 million acres of critical habitat, create 1.5 million hunters, and open hunting access to 500,000 additional acres,” he says, pointing to the alarming figure of 5,300 acres of wildlife habitat being lost in the U.S. every day. Good science is also critical.

“Threats to hunting will increase as more land is lost for hunting and as antis prove effective in capturing public support,” says Dickson. But hunters must bear the burden by focusing more on the resource and less on the hunt. “Some hunters are losing contact with the land and wildlife they hunt,” he says. “Technology and gimmicks abound while our relationship with nature has waned.”

There needs to be greater interest and emphasis on science and the work of biologists, who loomed so large in the wild turkey’s comeback in the first place.

“I expect most turkey hunters today would not even know who Henry Mosby and James Lewis were,” says Dickson.

TURKEY TRUTHS

Additional challenges such as limited state budgets, federal agencies that concentrate on endangered species, and to some degree a sense that turkeys are no longer in need of active management have impacted wild-turkey populations, says Dickson. “Without ample game to pursue,” says Thornton, “hunters lose interest. But our future has never been brighter. It’s great to be a turkey hunter.”