We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

The .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire, commonly known as the “Twenty-Two Win Mag,” was hatched back in 1959. At the time, “Gunsmoke,” “Bonanza,” “The Rifleman,” and dozens of Western films were celebrating horses, lever-actions, and revolvers. Every farm kid had a .22 LR (or wanted one). And once they started shooting, squirrels, rabbits, and coyotes, they wanted a faster one; a harder hitting one. So, Winchester gave them the .22 WMR, which shoots the same weight bullets as the .22 LR, only 650 fps faster.

“Magnum” is the perfect name for this cartridge because it does for the .22 rimfire what the .30-378 Weatherby Magnum did for the .308 Winchester: makes it shoot faster, flatter, and hit harder. And that’s been the trajectory of .22 rimfire cartridges since 1845.

.22 Rimfire History

The first rimfire was the Flobert BB Cap, essentially a muzzleloader cap (primer) with a BB (Bullet Breech) stuck atop it. Smith & Wesson expanded on the idea by lengthening the cap, adding about 4 grains of fine black powder and a 29-grain conical bullet to make the .22 Short. A slightly longer version in 1871 was the .22 Long. In 1887 Stevens Arm Co. raised the Long’s powder level to 5 grains, popped on a 40-grain round nose, and created the most popular rimfire cartridge in history, the .22 LR. But most popular is not the same as most powerful.

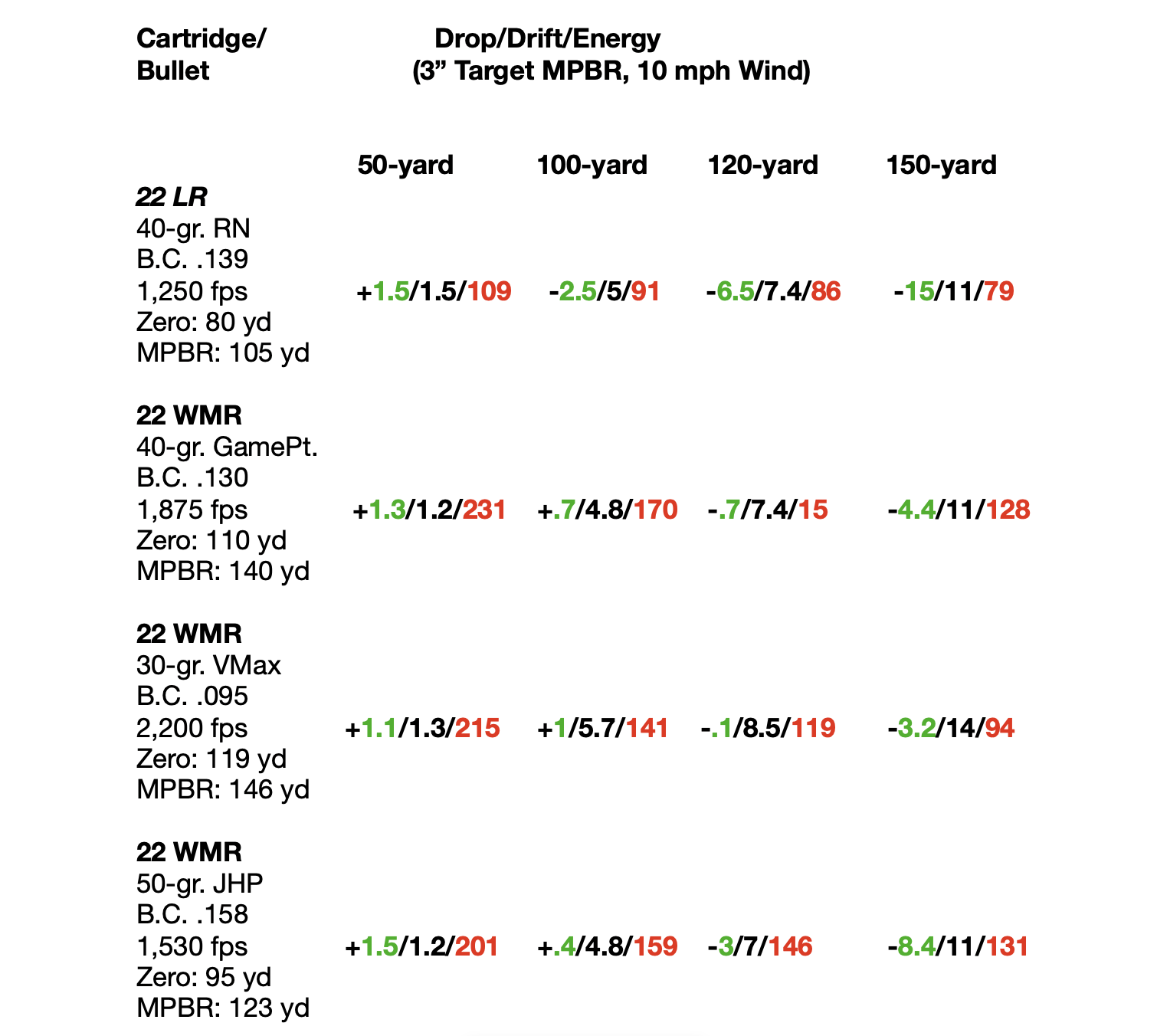

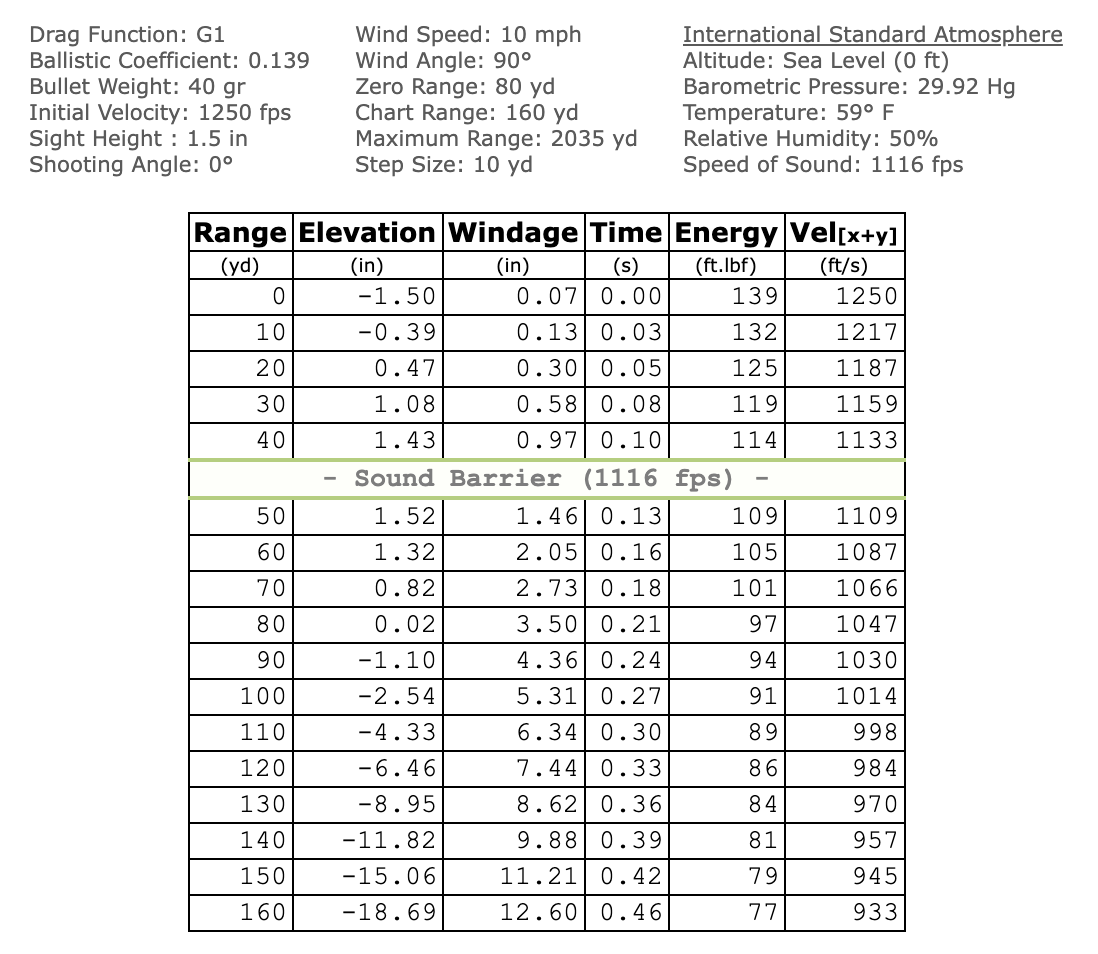

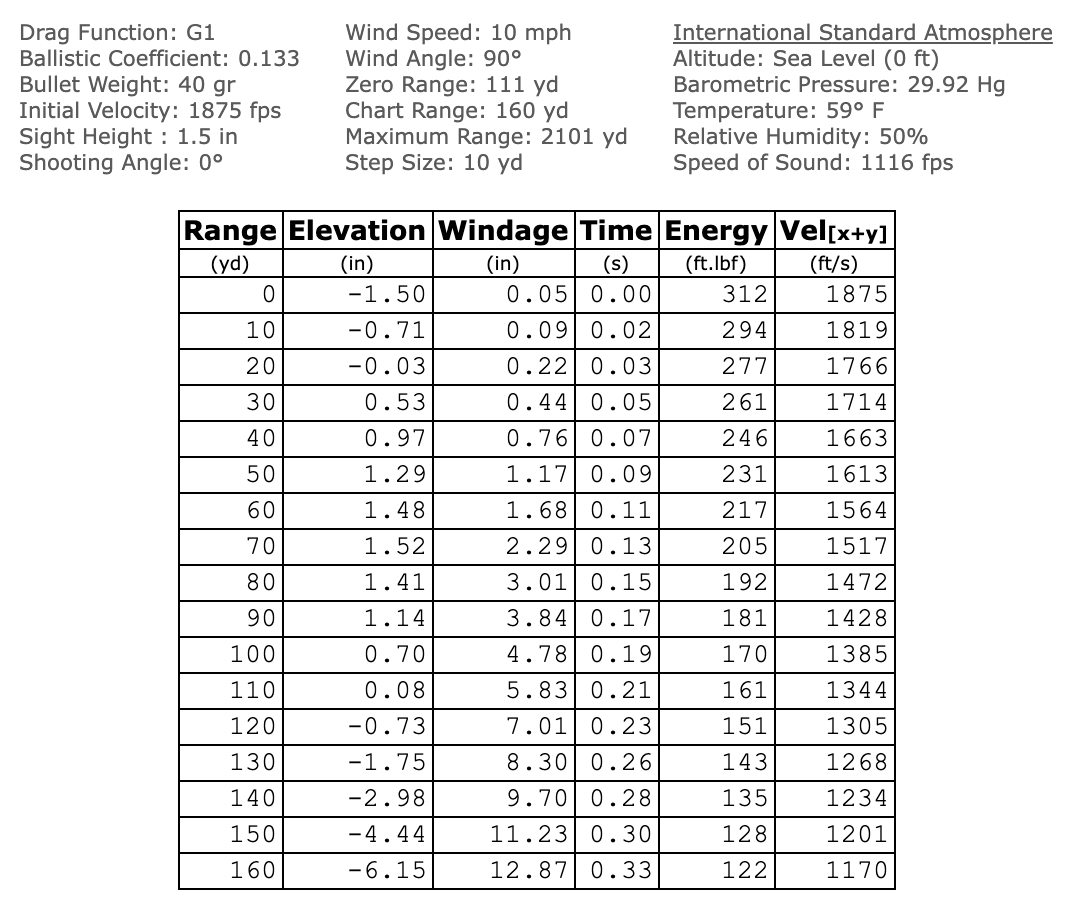

By the 1930s, high velocity .22 LR cartridges using smokeless powder were spitting 40-grain bullets about 1,250 fps. Winchester’s .22 Win Mag boosted that by 50 percent, pushing a 40-grain bullet 1,910 fps. That velocity increase adds 35 yards to the maximum point-blank range of the .22 LR when set up for a 3-inch diameter target. Bullet energy is 80 foot-pounds more at 100 yards.

Dramatic though that advance was, shooters still ask why .22 rimfires can’t shoot even faster. If .22 centerfires can push 40-grain bullets 3,000- to 4,000 fps, why can’t rimfires? The answer is pressure. Or too little of it.

Rimfire Pressure Limits

Rimfires function when the firing pin crushes the cartridge rim in which the sensitive priming mix sits. To accommodate this crush, the rim must be thin. Ignite too much powder to raise chamber pressures and you risk a case rupture with high velocity gases squirting back toward the shooter’s face and hands. SAAMI maximum average pressure (MAP) levels for both the .22 LR and WMR are 24,000 psi. MAP for the .22-250 Remington is 65,000 psi.

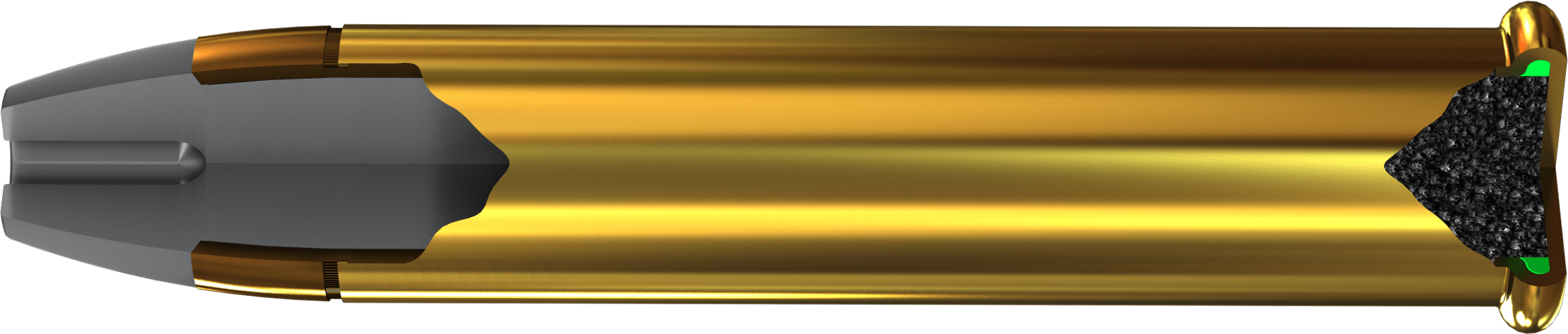

The .22 WMR achieves its velocity gain over the .22 LR via a case .457 inches longer, but also a body 0.024 inches wider. Roughly 5 to perhaps 7 grains of extremely fine smokeless ball powder are loaded in the .22 Mag. This compares to about 3 grains in the .22 LR. That means .22 WMRs will not fit in any .22 LR chamber, but .22 LRs will fit into .22 WMR chambers. This is not safe. Usually they won’t fire, but if they do the cases often split.

The .22 WMR Holds Velocity Longer

Another major difference between these two .22s is their bullets. Because the .22 LR’s case is as wide as its .223-inch bullet, the bullet’s heel must be stepped down in diameter to squeeze into the mouth of the case. The .22 WMR’s wider case allows a full diameter .224 bullet to be seated. The LR bullet has a slightly higher B.C. rating because it’s longer and narrower with more of its surface hiding in the slip stream of its nose. But the higher B.C. is not sufficient to match the increased muzzle velocity of the .22 WMR.

The quickest way to appreciate the .22 WMR is to consult ballistic trajectory charts. Not only does the 40-grain .22 WMR bullet shoot flatter than the 40-grain .22 LR, but at 130 yards it carries more energy (143 foot-pounds) than the 40-grain .22 LR bullet packs at the muzzle (139 foot-pounds). The 50-grain Federal JHP load holds onto 131 f-p clear out to 150 yards.

More .22 WMR Bullet Options

Just as the .22 LR can be found carrying several bullet weights, so can its magnum cousin. You’ll find .22 WMR ammo with 25- to 50-grain projectiles, even some non-toxic options. The lighter bullets step out faster, some hitting 2,200 fps. This means they shoot the flattest, but because they are less aerodynamically efficient, they lose energy more quickly to atmospheric drag.

What’s the .22 WMR Good For?

Too much and too little. This is a criticism often leveled against the .22 WMR. It hits with enough violence to ruin edible meat on small game (unless it’s a head shot) yet doesn’t hit quite hard enough for dramatic kills on coyotes. So why bother?

Pests are one reason. The ground squirrels, wood chucks, rock chucks, pigeons, and crows that loiter just a bit too far for the .22 LR are sitting ducks for a .22 WMR. Its 135-yard point-blank reach makes it easier to score at longer distances. On arrival, the bullets retain considerably more punch for a clean kill. This proves surprisingly effective on coyotes that tend to hang up between 100 and 150 yards. The .22 WMR’s remaining 150 or so foot-pounds of energy might not drop coyotes with the authority of a .243 Winchester, but it won’t demolish the valuable pelt when fur prices are high either. Chest-shot coyotes, red fox, and bobcats often dash 20 to 50 yards before giving up the ghost, but they will die if you shoot accurately. Often overlooked is the minimal recoil of the .22 WMR. Shooters should be able to keep targets in the scope through impact so they can call hits and misses, then compensate for subsequent shots.

Economy is another benefit. While .22 WMR ammo (currently about 50 cents per shot if you can find it) is pricier than .22 LR (about 20 cents per shot), it’s one-third the going rate of its nearest .22 centerfire competition ($1.50 per-shot .22 Hornet.) Many a farmer and rancher keep a .22 WMR in the truck for handling pests and varmints economically, appreciating the lower muzzle blast as well. But that is only relative. A .22 LR fired from a rifle barks at about 140 decibels, enough to cause permanent nerve damage. The larger powder capacity of the .22 WMR increases that impulse blast significantly, some think as much as four times more. But even if only two times more, it’s nothing to ignore. The safest, smartest option is hearing protection for all shots.

Don’t Confuse the .22 WRF with the .22 WMR

A confusing oddity in the .22 rimfire world is the .22 Winchester Rim Fire (WRF). The name and initials are so similar to the .22 WMR that it’s easy to get confused. These are different cartridges. The WRF was an 1890 creation that predated the WMR that wouldn’t appear until 69 years later. It drove a 45-grain flat-nose bullet about 1,400 fps. Winchester, Stevens, and Remington rifles were chambered for it and Remington even loaded it with a round nose bullet, calling it the .22 Remington Special.

Like the .22 WMR, the old WRF is wider and longer than the LR. It is not, however, the same width or length as the WMR, yet it will fit and fire safely in WMR chambers. Standard .22 LR cartridges will fit a .22 WRF, but loosely. They may or may not fire, will likely rupture if they do, and may not extract. In short, it is neither recommended nor safe to fire .22 LR ammo in an old .22 WRF rifle.

The .22 WRF is considered obsolete, but ammo companies will occasionally load it. CCI generally has it in inventory, so if you inherit an old rifle chambered in this cartridge, you should be able to put it to use.

Here’s a quick look at the ballistic differences between the .22 WMR, LR, and WRF:

.22 Win Mag

- MAP: 24,000 psi

- Case length: 1.055 in.

- COAL: 1.35 in.

- Rim: .294 in.

- Body: .242 in.

- Bullet .224 in.

- Twist: 1:16

.22 LR

- MAP: 24,000 psi

- Case Length: .613 in.

- COAL: 1 in.

- Rim: .278 in.

- Body: .226 in.

- Bullet: rebated heel

- Twist: 1:16

.22 WRF

- MAP: 24,000 psi

- Case Length: .965 in.

- COAL: 1.18 in.

- Rim: .300 in.

- Body: .243 in.

- Bullet: .2285 in.

- Twist: 1:14

Read Next: Classic .22 Rimfires That Still Make Great Squirrel Hunting Rifles

Two Final .22 Rimfires

As if I haven’t confused you enough with all these .22 rimfires there are two more worth noting: the obsolete .22 Winchester Auto and .22 Remington Auto. Both were uniquely sized cartridges meant to fire only in respective autoloaders from each company. They are roughly the ballistic equal of the .22 LR, but were designed so that black powder .22 LR cartridges of the era could not be fired in the autoloaders and foul them.

Given the pressure limitations of rimfires, the .22 WMR is likely the end of the line for .22 rimfire development. If you’re pining for more reach and punch than your .22 LR provides, the .22 WMR is your best bet.