We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

The verb “ricochet” is defined as the occurrence of a bullet rebounding off a surface. As a noun, the term ricochet describes a projectile that has rebounded off a surface. In other words, a bullet can ricochet, and a bullet can be a ricochet. And ricochets are much more common than you think. They happen frequently on shooting ranges, while hunting, and when you’re plinking at the farm. But what causes ricochets, and how can you avoid them?

Bullets Want to Keep Moving

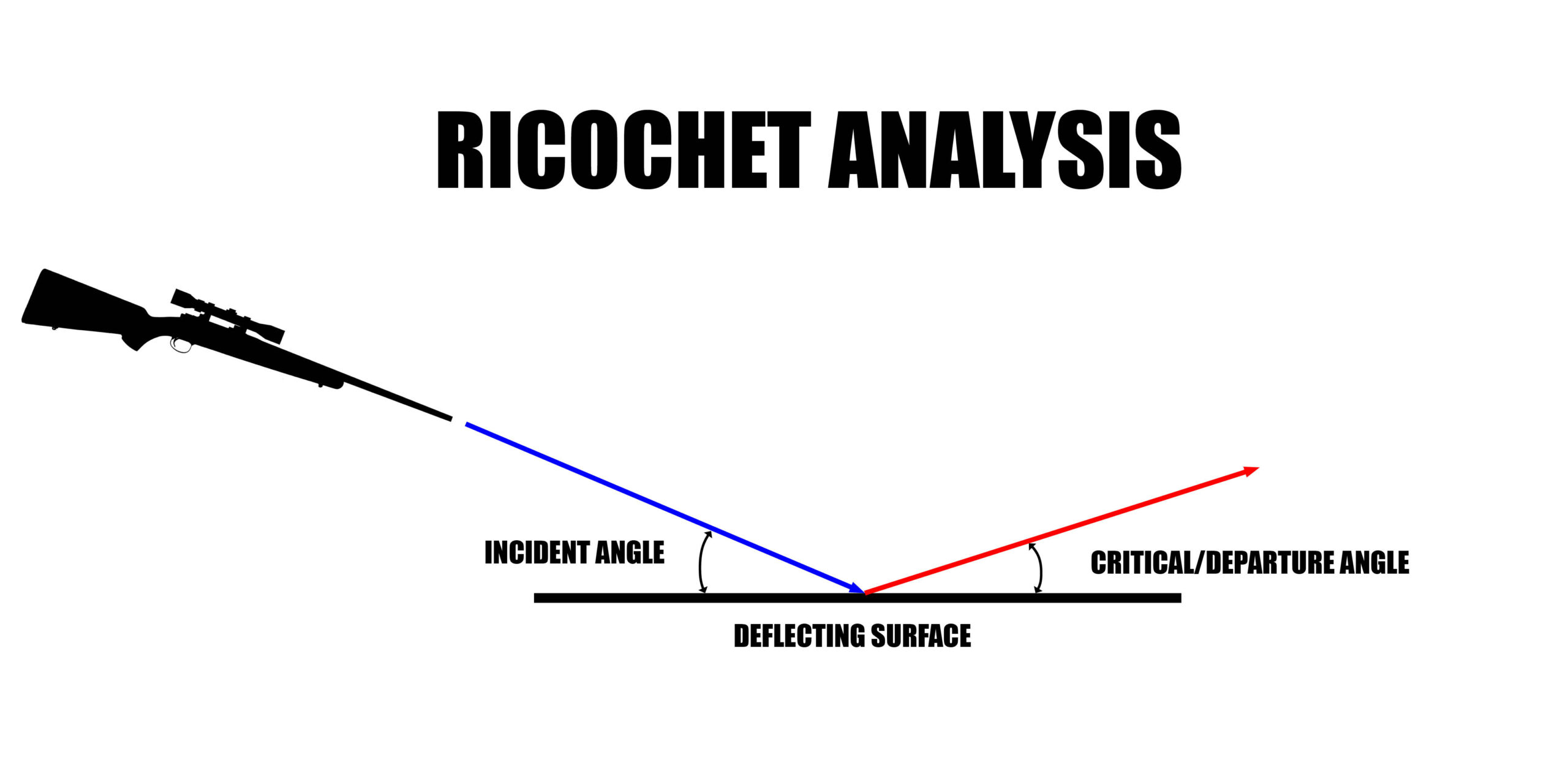

Because of their high velocity, and because of Newton’s First Law—a body in motion tends to remain in motion—bullets want to keep moving even after hitting something. Maybe the best illustration of a ricochet is a bounce pass in basketball. The ball strikes the gym floor or driveway at an angle and is deflected away from that hard surface in a very similar angle. Though some people believe a ricochet can travel further than a bullet fired at maximum elevation for range, this is a myth; impact substantially reduces bullet velocity.

Also, the surface causing the ricochet does not have to be harder than the bullet. For example, depending on the angle of incidence, a tree could cause a ricochet. If the angle is acute enough, and if the tree does not absorb all the bullet’s energy, the bullet will ricochet or deflect.

Unlike with a predictable bounce pass, where the basketball is not damaged or altered due to impact, the angle of ricochet is very difficult to predict with mangled bullets. In most cases however, the angle of departure is less than the incident angle, but that’s not always the case.

While hunting in Newfoundland, I shot at a bull moose at about 65 yards. The bullet first ricocheted off a small limb only a few yards from the bull and altered the point of impact by about 15 inches. I also have a friend in Africa who shot at a baboon in his yard. The bullet hit a rock, arced high for about 300 yards, and then landed in a neighbor’s yard only a few feet from where he and his wife were taking their evening tea. Both shots were essentially bounce passes gone bad.

This is the problem with trying to predict bullet ricochets. You can skip a rock across a concrete parking lot with predictably. But with a bullet traveling at extreme velocity, you have no way of knowing the level of damage the bullet will sustain from impact, or how that damage and loss of gyroscopic stability will influence the resulting ricochet. Where will it land? Nobody knows.

One of the reasons you hear the whining whirl of ricochets is due to the bullet impacting a rock or rocks at or just under the surface; even small rocks can cause the ricochet. That odd sound is the result of the bullet’s loss of stability as it continues to fly through the air.

Steel Doesn’t Always Stop a Ricochet

Steel targets can also cause ricochets, sometimes with the angle of incidence and critical angle near 180 degrees apart and the bullet rebounds back towards the shooter. This happens when the surface of a steel target becomes cratered, and a high-velocity bullet impacts the crater. The steel stops forward motion, but due to the velocity and construction of the bullet, the steel is unable to fully disintegrate the projectile and absorb all its energy. The bullet has to go somewhere, so the cratered steel sends it in the path of least resistance.

Good, well-made, and smooth-faced steel targets actually use ricochet to their advantage by safely deflecting bullets towards the ground. Given the right angle of incidence, the right bullet, and right velocity, almost anything can cause a ricochet. This includes water, an animal’s skull, an Army helmet (which is designed to increase the incidence of ricochet), trees, twigs, concrete, asphalt, hard-packed soil, and rocks. The list is endless.

In fact, ricochets can occur once a bullet enters the body cavity of a game animal. Have you ever field-dressed a deer and found the bullet somewhere way off the track it should have followed? This is because it impacted bone or cartilage, altered its shape and changed direction, and essentially ricocheted inside the animal.

The fourth rule of firearms safety is generally stated as, “Always be sure of your target and what is beyond.” This is really the best guidance available for avoiding ricochets. Don’t shoot anything but a shotgun onto water and don’t shoot at targets resting on concrete or a paved surface. Don’t shoot steel targets in poor condition, and don’t shoot rocks, pieces of steel, or any hard surface at extreme acute angles. Another way to avoid ricochets is to use ammunition loaded with frangible bullets. Though not suitable for hunting, they can add safety to your practice.