Marty Tillard’s pickup crawled up the mud-slick road, the granny gear whining as the truck moved steadily upward. Outside a frigid wind sent tiny ice crystals sandblasting against the windshield. In 24 hours, the blue skies of southern Wyoming had retreated from the clouds of an incoming snowstorm.

Down in the flats the ground had seemed barren and broken, but higher up, the prairie gave way to patches of sage and stunted cedars that were slowly icing over with snow. Off to my right the canyon forked, a sage-covered point separating the two sides.

“Hold it,” I said. Something had caught my eye. Marty hit the brakes. “Back up a hair.” Was that a stick poking out or something else?

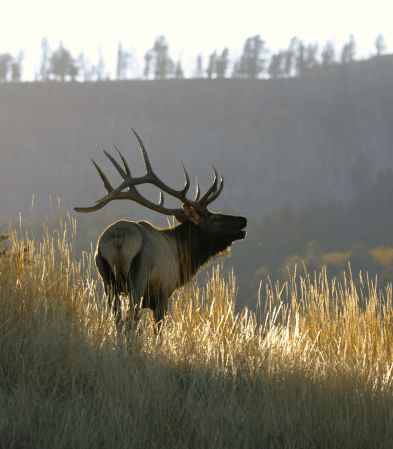

I swung my binocular onto the spot. There was the forked stick and there was another. Now there was movement in the bottom of the binocular’s frame. An ear flickered. Suddenly, as if backing away from a painting until the whole picture comes into focus, I could see it, the white face of a bedded mule deer doe, looking right at me. And just above her, still as stone, was the head of a buck, his antlers just clearing the tops of the sagebrush.

His grayish form blended perfectly with the blue-gray sage. Between the snow building on the sage tops and the overcast skies, it would have been very easy to have passed right by, but the dark, forked tops of his antlers were just the kind of visual clue I’d been looking for.

“It’s a buck,” I said, straining to get a better look at his antlers. I didn’t want to get too excited, but my first impression was that he had good mass. On the side that I could see he was a typical four, but I couldn’t see his other side.

“Let’s keep moving,” I said, not wanting to rouse the buck’s suspicion. He was bedded and calm and I wanted to keep it that way, at least until we could see him a bit better. Marty drove up the road, which topped out at an old well-drilling site. We pulled the truck in behind a small outbuilding, inching the nose out so that we could bring the big 20-60X Swarovski spotting scope to bear from its window mount.

Marty was on him now, eyeing him carefully through the big lens. “He’s a typical four by four, with nice eye guards. If he has any kind of spread, he’s gonna be a real nice buck,” he said. I was already slipping into my camo overpants, in anticipation of a stalk. The wind was fierce, and even wearing several layers of clothes, I felt chilled after leaving the warmth of the cab. Now I was on my binocular, again trying to gauge his spread, but the buck never moved. Studying the ground around him we counted at least four does and figured there were probably a few more tucked away in the sage. Making any kind of stalk from where we were would be impossible without spooking the entire herd.

Just then, the buck swung his mighty head. “He’s out past his ears,” the two of us said at once. This was the first day of our four-day hunt and already we had a really good-looking buck bedded not 400 yards away. “What do you think, Marty?” I asked. “I know it’s only the first day of the hunt, but you know your deer. If you think we should try to take him, we will.”

Marty thought for a long moment. “Well,” he began, his eyes still riveted on the buck through the spotting scope, “the weather’s only going to get worse.” He turned to face me. “I think we could hunt all week and not find a better deer. Let’s go for it.”

I’d come to Wyoming with Rob Fancher, who does all of the PR work for Swarovski U.S.A. Over the years the two of us have hunted grouse and deer at several Eastern locations, but this was the first time we’d chased Western game together. That morning, Rob had headed off with Marty’s son Casey to a different part of the 29,000-acre ranch, while Marty and I hunted the higher country.

The Tillard family has been ranching here for several generations. Cattle and sheep are both revenue-makers for the ranch, but over the years the Tillards have paid close attention to their mule deer numbers, managing the land for quality deer. Every season they take a few mature bucks and cull a deer or two. This has ensured top-notch hunting, despite the fact that mule deer numbers have been adversely affected by drought in many areas of the West [see sidebar below].

The nice part about hunting the October rifle season is that it overlaps with the pronghorn season, so you can hunt two species at once. This part of Wyoming doesn’t produce many record bucks (a good pronghorn here runs 15 inches or so), but there are hundreds of animals roaming the ranch, so finding pronghorns is never a problem. There are lots of mule deer, too, but the wise old bucks are pretty cagey. Just locating them in tens of thousands of acres of land is no easy task. And because the land is so open, getting close enough for a shot is an equal challenge.

This was why I was pleased that I’d taken my old Model 700 in 7mm Rem. Mag. I’ve killed a lot of Western game with this rifle over the years. Shooting Federal’s 175-grain Trophy Bonded Bear Claw loads, this gun will produce 1-inch groups all day. Granted, these bullets are a bit heavy for mule deer and are certainly way more than you need for pronghorns, but my rifle shoots this ammunition so well that I just didn’t want to change anything. If I connected, the animal would certainly never notice the heavier bullet weight.

The bedded deer were on the alert now. We couldn’t stalk them from where we were and we were certainly much too far for a shot, particularly with the vicious crosswind that was now howling down the canyon.

“Let’s get back in the truck,” Marty suggested. “I think we can creep on past without spooking them. Once we’re down below them and out of sight, we can park the truck and hike back up. I doubt they’re going anywhere in this weather.”

As the truck wound its way back down the hill, I never took my eyes off the old buck. He still lay there, rock solid, but the does around him were getting antsy. Several hundred yards down the road we dropped out of sight and the two of us bailed out. I grabbed my old day pack and shooting sticks. I wanted the option of using the backpack for a rest, if I could shoot prone; I’d use the sticks if I were forced to take a sitting shot.

As it turned out, we were able to work our way down a little gully that brought us within range of the deer, but when we popped our heads up for a look-see, they had moved. All of them were now quietly feeding their way out across the sage flats. I couldn’t shoot prone in the thick sage so I quickly got into a sitting position with the rifle on the sticks. The deer hadn’t made us yet, but they were steadily moving away. The sticks helped a lot, but big gusts of wind were making it tough to get steady. I waited until the crosshairs settled on the big buck’s vitals, but just as I touched off, a gust blew me sideways. The 7 Mag. boomed and the buck took off.

“You’re just over the top of him,” Marty said. Now my buck was putting as much real estate as possible between us. All I could do was watch as he headed up the canyon, jumped a stock fence and trotted on. Then he stopped, giving us that over-the-shoulder look that mule deer always do when they know they’re safe. Most times, the glance is just a momentary pause before they bolt into the next county, but to my surprise, the buck dropped his head and began to feed.

A large hill rolled up to his left. If we could circle around, and the buck stayed where he was, we just might get a second chance. Marty and I doubled back up the canyon, keeping the steep hill between the buck and us.

Fifteen minutes later we belly-crawled to the crest of the hill. Was he still there? Yes, there he was, grazing quietly, his does all around him, occasionally shooting a glance back down the canyon to where we had been.

This time I lay down and nestled the rifle into my day pack. With my body laid out flat and the rifle supported, there wasn’t a hint of movement in the crosshairs. I cranked the scope’s power to 6X and took up the slack in the trigger. Now he was turning broadside; now he stopped. The trigger broke cleanly and I felt a little jump of surprise at the shot. I heard the Bear Claw whump home. The buck staggered sideways, ran in a short half-circle and fell over. Then Marty was slapping me on the back and the two of us were war-whooping and slapping high-fives.

Walking up on the buck a few minutes later, we saw a near-perfect four by four with nice eye guards. Best of all, he seemed to grow bigger with each approaching step. We quickly field-dressed him and then headed for town, where the guys at the meat processor’s said he was one of the best bucks they’d seen all year.

The snow continued to fall that night. By the next morning the grassy fields we had seen the day before were completely covered.

“We could never have made it back up to where you and I were yesterday,” Marty exclaimed, which made me feel even better. What’s more, we now had two days to look for a good pronghorn. We found one, too, that gave us a terrific stalk and a 150-yard shot. And Rob got his mule deer, a huge three by three that Marty asked him to cull. The old buck was well past his prime, with gigantic bases and a stiff-legged gait that showed his age. Rob took him at 325 yards with a single shot from his custom .280.

With land that is much the same as it was in Lewis and Clark’s day, you understand why people are drawn to Wyoming to hunt. It’s about the wild places where pronghorns are abundant and great mule deer aren’t just something to dream about.

State of the Mule Deer

According to Al Langston of the Wyoming Game and Fish department, this year should be about average for mule deer hunting. This past winter was relatively mild in most deer wintering areas, and a fairly wet spring in most places has vegetation and forage growing well. Overall, however, the population isn’t as high as it should be because of the severe drought Wyoming has experienced in the past few years. Langston expects it will take several more wet springs to bring the forage and the deer population back up.

A good public-land area where hunters have a reasonable chance of taking a trophy muley is in the Bridger-Teton National Forest. This is rugged country with a low deer density, allowing the few deer that call it home to live to old age. For a better chance for success and easier terrain, look at private lands close to the towns of Casper and Sheridan. Contact: Al Langston/Wyoming Department of Game and Fish: 307-777-4600.–Will Brantley

Essentials

Newcomers to Western hunting will find conditions far different from typical hunting situations in many parts of the U.S. Here are three essentials I never leave home without when I head out West to hunt.

Guns & Loads While hills and gullies generally allow you to get within 150 yards of mule deer and pronghorns (and sometimes much closer), occasionally you will be faced with a shot that is 300 yards or farther. This is not the terrain for marginal cartridges. To me, good pronghorn and mule deer cartridges start with the .270 Win. From there, the .280 Rem., 7mm Remington or Weatherby Magnums and .30/06 are ideal choices, offering flat-shooting capability in relatively light rifles that are easy to carry. At the upper end of the spectrum, I’d add the .300 Win. Mag. Though the .300 is needlessly overgunned for pronghorns, it does provide a good general-purpose round, particularly if you’re going to be hunting higher country where elk are a possibility.

Hunting Optics

One thing to consider when choosing a binocular for use out West is that windy conditions are very common. In a howling wind like the one we hunted in, hand movements are really magnified, which is why I prefer 8X to 10X binoculars. The Swarovski 8×30 SLC binocular I glassed with offered a nice compromise between weight, size and magnification while offering a broader field of view for locating game. If you need to see something way out there, use a spotting scope.

We used Swarovski’s new ATS 65 HD spotting scope on a window mount. The beauty of this scope, aside from its incredible optical quality, is that the angled eyepiece rotates, making it much easier to use when you’re seated in a vehicle. The wide focus ring is also a handy feature when you’re wearing gloves.

High-plains hunts present all kinds of shooting opportunities, which is why I like the flexibility of a variable-power scope. When stalking in close (as we did on our pronghorn) I had my 2.5-10X Habicht cranked all the way down to offer the widest field of view possible. This helped me pick up the animal quickly when we finally popped over the hill in range. Once the target was acquired, I still had plenty of time to crank up the power before making a shot.

Rifle Rests

The late Bob Milek, famed gun writer and Wyoming native, always carried a day pack with him that could quickly be slid under the forend to provide a steady rest for shooting prone. I’ve gotten in the habit of carrying one, too.

If sage brush or other obstacles prevent me from lying down, the next best option is to shoot from a sitting position. This is where a good set of shooting sticks comes in handy. I use Underwood Shooting Sticks, but similar types are available from Cabela’s.