I started hunting Fulton County, Illinois, when I was five years old. I hunted with my father, who passed away from a heart attack when he was only 34. I was 10. After he died, I squirrel and rabbit hunted a bit with my uncle, but didn’t duck hunt again until I was in my 20s. When I returned, it was near the same place I’d grown up duck hunting.

Canton, the closest town to the fields and strip-mine lakes we hunt, was once known for giant Canada geese. There was a power plant that used one of the old coal mines as a discharge lake, and that kept water open all season long. Tens of thousands of honkers would roost there and run a gauntlet of hunters waiting in cut corn and beans each morning and afternoon of the season.

It’s not like that anymore. The power plant shut down and the geese have shifted west and short-stopped us. But if you pick the right weather days to hunt, you can kill a few ducks and geese. And that was our plan. My brother and I looked at the forecasts and set our dates. We planned to hunt in late December, just after Christmas.

COVID Tries to Cancel Christmas

This time last year, I wrote about the trials of parenting in the COVID-19 era, and how I used hunting to escape—if only for a time—the constant stress of the pandemic. Like many of you, I presumed 2021 would be better for everyone. And in some ways, it was. I was able to reconvene with my extended family and see friends I hadn’t been able to in over a year. I took my 8-year-old son to a Chicago Cubs game this summer. Our family went on vacation for the first time since the pandemic hit. Life was returning to normal.

But then the pandemic surged again, and 2021 began to feel an awful lot like 2020 as new COVID variants emerged. The uptick in COVID cases the last two months made me feel even more panicked. I’m not all that concerned with the pandemic itself anymore, as it’s become less deadly, but the restrictions, mandates, and political fodder that come with each new strain are mentally taxing. And that was on top of life’s usual stressors. Both my wife and son had surgeries this year. I worried about them before, during, and after their procedures. I didn’t hunt as much at home here in Illinois, because I needed to take care of my family. That caused more stress because getting into the woods with my squirrel dog or sitting in a duck blind is important to my mental health. Without as much of it, I felt slightly off.

This holiday season has not been the uplifting, happy gathering I wanted. My wife’s family Christmas was canceled because several relatives tested positive or were at home sick awaiting results. A few days later, we found out our son had COVID.

He had been looking forward to having a friend over for weeks, and now it couldn’t happen because he was sick. He cried for a long time and kept repeating, “I just want to wake up from this bad dream.” It’s hard to make your kid feel better when there’s nothing for him to look forward to but another week inside, closed off from everyone except his mom and dad. It’s even more difficult when you don’t feel all that hopeful yourself.

When that mood sets in, I must disconnect before I get overwhelmed. And to do that, I go hunting. Thankfully, my brother and I decided we would end duck season together, hunting the last few days before ducks were out. We were still able to go the day after Christmas and again on the final day of the season before I found out my boy had tested positive.

A Familiar Waterfowl Feeling

On that first afternoon hunting near Canton, my brother Carl and I watched specklebellies and flocks of Canadas trading between two roosts. They lifted off the water, flew sky-high, and then descended into another pool. Smart birds. In this part of the country, if a goose flies over a blind or pit, it’s likely getting shot at. Doesn’t matter if it’s 25 yards off the deck or 150—hunters come out here to shoot, even if it’s not always the best shot.

My brother and I knew that the last 30 minutes of shooting light would be our best chance to kill a bird. We just needed the right flock to fly in our direction. A string of honkers came off the water a few hundred yards in front of us. They were big. We call them Canton geese because they’re locals that never migrate, programmed to go where they know they will be safe. But this flock screwed up.

They were flying fast, but not high enough, and when they skirted the edge of our small wetland, I rose, pulled the trigger twice, and the lead bird crashed into a thicket of Russian olive.

I ran up the hillside to look for the bird. My brother stayed below on the levee and spotted it first. So, I worked my way toward his voice and found the goose.

“Oh Carl,” I sad.

He knew immediately what that meant. “You shot a band? Nice!”

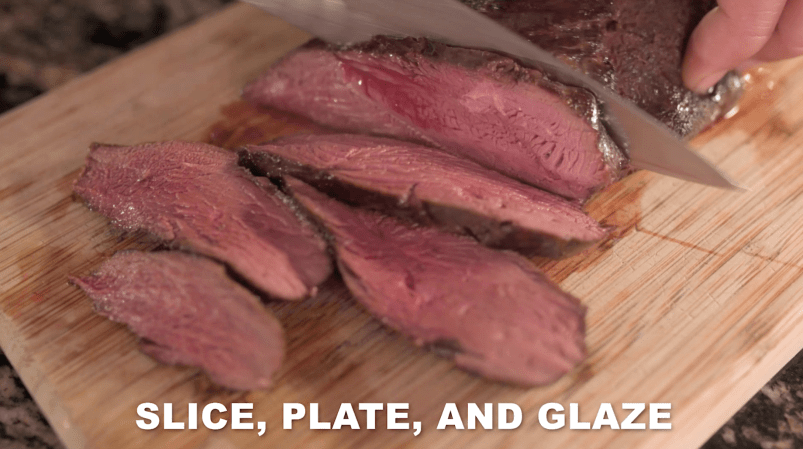

We both also knew the bird was a local, and later found out the goose had been banded only two miles from where I shot it. It was massive, weighing over 14 pounds. When I cut the breasts out at home on the tailgate of my truck, they were the size of two Easter hams.

It had been years since I shot a Canton band, and reminded me of my dad and all the fun we’d had around here. While he brushed in goose blinds in the summer I would play in the standing corn. When the season came, I built sandcastles on the banks of the Illinois River in the early mornings. Later, we’d sit together in small-town taverns, eating foot-long hot dogs and frozen Snickers bars. I needed that band more than I knew.

Two days later, Carl and I spent one last afternoon in a Canton duck blind. We were hunting flooded corn, the spot where all the mallards would come into as shooting light set on another Illinois season. A few ducks did fly into the decoys before time was up. We shot four hens: three mallards, and one wigeon—an ugly but classic central Illinois lanyard of ducks. We take what we can get here.

The two of us picked up decoys and watched the mallards drop into the corn like they were falling down an elevator shaft. I love how ducks backpedal over the tops of cornstalks, sticking their necks out just before they cannonball into the water. One moment they are majestic in flight, their wings cupped; the next they are like a fat kid jumping off the diving board into the swimming pool. I wanted to grab my phone and record the moment to watch over and again until next season, but my hands were full of cased shotguns and Mojo poles. No matter—I’ll remember that scene in my mind for years to come.