We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

ORDINARILY a man doesn’t have any advance warning when the tight squeezes of his life are coming up. Certainly I had none that day in Alaska.

Maybe the red squirrel had nothing to do with it. Maybe there was some other reason why the brown bear left the moose trail she was following on the mountain a hundred yards above me, and came down to look me over.

She may have spotted me as I came slogging up the slope and mistaken me for a small moose. Or perhaps she knew I was a man but just didn’t want me in the neighborhood.

In any case, I shall always think that if I hadn’t seen the squirrel and stopped to fool around with it the rest wouldn’t have happened. And in that event I’d have missed the closest shave I’ve had in almost twenty years on the game trails of Alaska.

Read Next: The Best Bear Defense Handguns

I was on a pack trip along the Chickaloon River at the time, in a remote section of the Kenai Peninsula. Not a pack-train trip — I was traveling afoot, carrying my grub, sleeping bag, and equipment on a packboard on my back. My object was to get pictures of the big Kenai moose. It was October, their rutting season, and a good time to stalk them with either gun or camera. I’d told my wife when I left our cabin on Kenai Lake that I’d be gone a month, but the moose hunting was exceptionally good and time slipped away fast. I had been out thirty-five days the morning the bear jumped me.

By that time I’d walked better than 200 miles, carrying a pack of about sixty pounds. Hunting big game with a camera is no soft job, but I’d made some good pictures of moose, including close-ups of big bulls and a movie record of a brisk scrap between two rivals. In thirty-five days I had not seen another human.

The weather had turned bad, with a lot of cold rain. Finally the rain changed to snow and a foot of it came down in one night — a powdery fall that started to soften and settle as soon as the sun rose next morning. I decided to make one more trip out from my base camp and then start for home.

A few miles from camp, down a small creek that ran into the Chickaloon, I had located earlier a big bench on the side of a mountain, grown up with willow, quaking aspen, and cottonwood. There was plenty of moose food there, and an unusual concentration of moose. Shortly before the snow came I had spotted one big bull with seven cows in his harem. If they were still together I wanted pictures of them. I left camp right after breakfast and headed that way.

On that trip, for the first time, I was carrying a Colt .38 Special double-action revolver, a Police Positive. Never before had I packed anything heavier than a .22 automatic for picking off ptarmigan, grouse, and rabbits for the pot. But my wife, worried about bears, finally talked me into switching over to the .38. That was the best bill of goods I ever bought! I took good care of the handgun, carrying it in a shoulder holster so it wouldn’t catch in the brush, and keeping it clean and dry.

I followed the creek down toward the bench. When I was almost directly below it I started to climb, picking my way through open stands of spruce and birch as noiselessly as possible and keeping the wind in my face.

I was within 300 feet of the bench when I saw the red squirrel feeding on cones in a thin patch of alder. Just for the heck of it I walked over and talked to him in an undertone until he set up an excited chattering. I realized afterward that between us we made noise enough to reach the ears of the bear up on the bench. The squirrel’s scolding warned her that something out of the ordinary was going on.

Her tracks told me after the affair was over that she had been traveling on a moose trail that followed the bench. Apparently, when I stopped to tease the squirrel, she turned downhill to investigate.

I left the squirrel and went on, looking for the best going up the mountainside. Seventy yards ahead was a thick stand of young spruce, roughly circular and about 100 feet across. I’d have to go around it. I picked out a route along the lower edge and plodded up.

I was twenty feet from the thicket when I heard a commotion on the far side. It sounded like a bull moose breaking brush, and instantly I visualized a chance for pictures. I decided to set my camera up and get ready for him at close range if he came through the thicket toward me.

I leaned forward to ease an arm out of my pack straps, and through the spruce I caught sight of a patch of brown thirty yards away. The moose? No, something about it wasn’t right. I crouched for a better look under the branches and stared at a bear head that looked as big as a washtub!

I took it all in in one quick glimpse, ears, muzzle, color. Then the head vanished in the snow-hung growth and I heard brush crack — the noise of a heavy animal running straight at me.

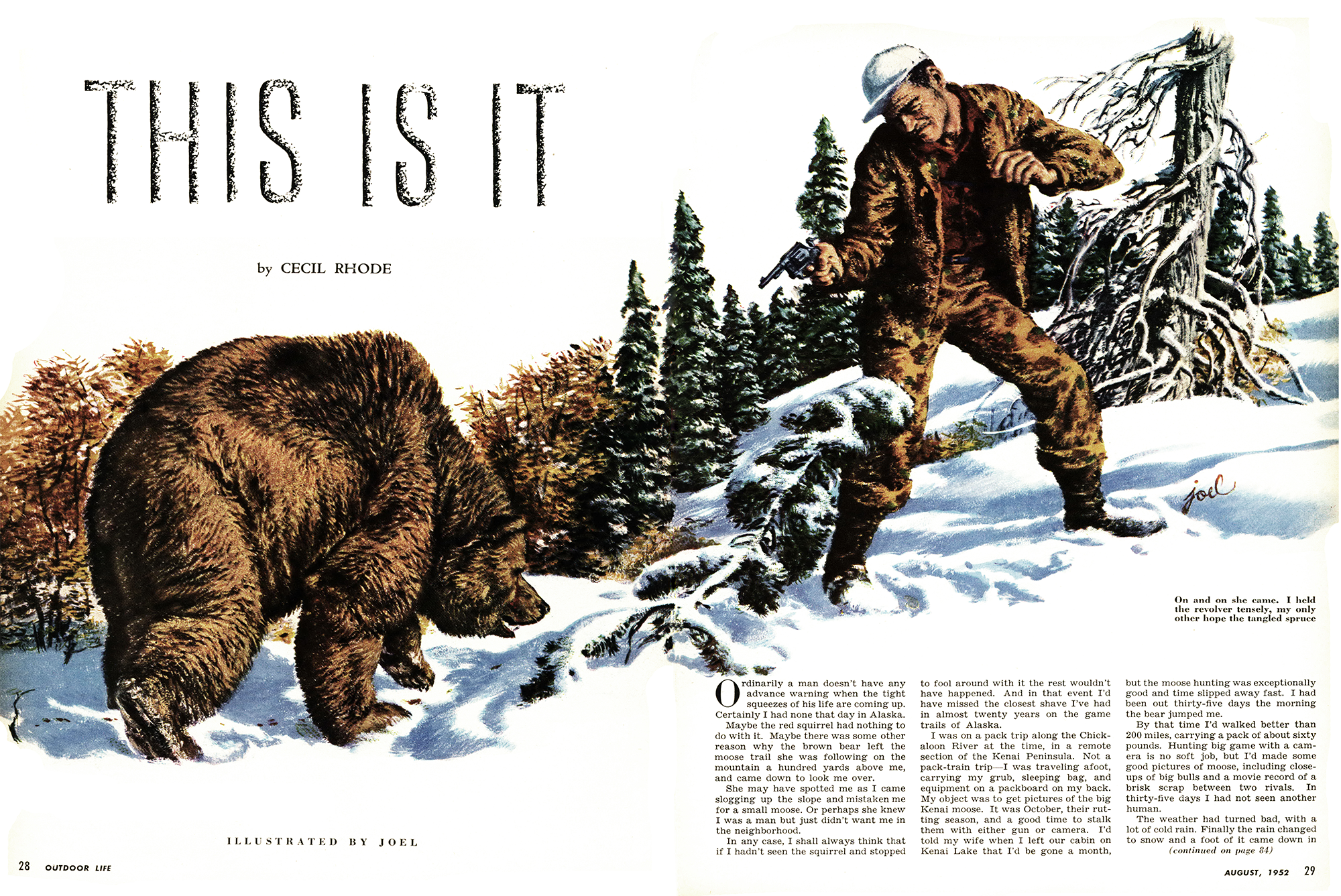

I got out of that packboard like an eel sliding through a greased chute, jerked off my gloves, and whipped the .38 from its holster. I swung the gun up just as the bear’s big brown head broke out of the brush four steps from me and halted there, seeming to float to a stop.

I was forty miles from home and — I now realized — in bear country. I might need those nine shells badly before I got back to the cabin on Kenai Lake.

I’ll never know why she didn’t finish her charge, unless she had believed she was stalking a moose and jerked to a surprised halt when she found herself facing a man instead. Anyway, she gave me the chance I needed.

She stood at the edge of the brush, so close I could have flipped a pebble into her face, acting as if she had lost track of me. She lifted her head and cocked it to one side, and her nose wrinkled as she tested the wind.

I was reluctant to risk a shot from the handgun if I didn’t have to. It was no weapon for the job, and I didn’t want to shoot until I was sure she meant to come on.

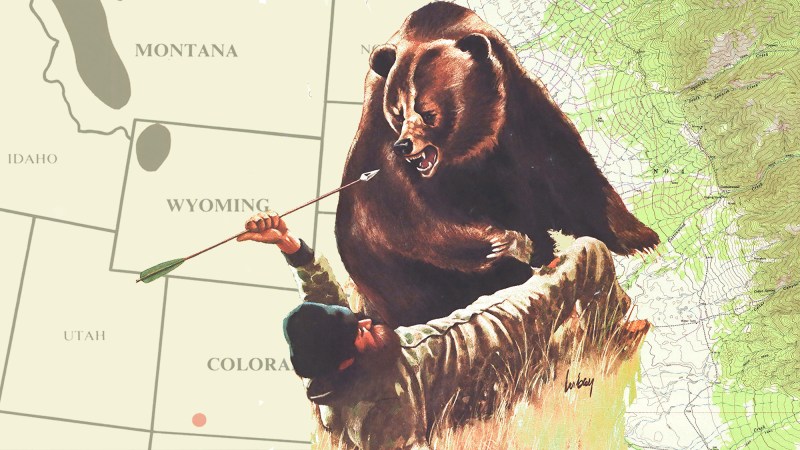

I HAVE BEEN ASKED many times since whether I was scared. Put yourself in my shoes. The bear would have weighed not less than 700 pounds and she had trouble written all over her. And when I paced the distance later it was exactly eleven feet between her tracks and mine. You can bet your last dollar I was scared, and I’m not ashamed to admit it. But luckily I wasn’t rattled. I knew my only chance was to stand still and count on the .38 to do the job if it had to. Somehow I believed it would. Nevertheless, I recall the chill phrase “This is it!” ticking through my brain.

It all happened a lot faster than I can set it down here, of course. After a second or two the bear lowered her head and I decided not to wait any longer. I was sure she had made up her mind to come for me, and with her head down I had a chance to smash the 158-grain bullet flat against her skull, where it wouldn’t be likely to glance off and not ram through to her brain.

At that range I couldn’t miss. I brought the gun down on her head as deliberately as if I had been shooting at a match target. The slug smacked about an inch to one side of center, and I saw blood fly. She slumped like a boxer knocked half off his feet, and I felt pretty good — for a second or two.

Then she straightened up and stood staring at me. I leveled the gun, waiting for her head to drop again. Instead she did the last thing in the world I expected. She turned slowly and calmly, and walked back into the thicket, out of sight.

I thought she moved as if she were a pretty sick bear, but I didn’t count too much on it. For maybe a minute I heard nothing more. I waited, tense and ready, expecting her to come at me again from any one of a dozen places. Then, at the far side of the spruce clump, hell broke loose.

She let go a series of roaring bawls that were enough to turn a man’s hair white. There was a scuffle, then all of a sudden I heard a cub squall. That was my first inkling that there were cubs in the act, and it wasn’t a pleasant thought. It explained a lot of things and it also meant, almost certainly, that the show wasn’t over. I could count on her to be really vindictive now!

I looked around desperately for a tree. The best I could locate was a dead spruce, standing by itself in the open about twenty feet to my left. But it had a tangle of bleached branches all the way to the ground and I saw that I’d have to claw my way into it to reach the trunk. It wasn’t a tree a man could climb in a hurry, even in desperation. All the same, I started to edge toward it, moving very carefully. If the bear had forgotten where I was I didn’t want to remind her.

Her fight with the cubs didn’t last long but it was nasty while it lasted. The old lady seemed to be cuffing the daylights out of her whole family. When the racket stopped, I felt pretty sure she was coming back after me. I stopped sidling toward the tree and braced myself, with the Colt cocked and ready, trying to watch the entire edge of the thicket at one time.

SHE DID EXACTLY what she had done before, except that this time I didn’t hear her coming through the brush. She appeared without warning, twenty feet away, and again she slid to a stop at the edge of the thicket.

Her head was lowered, giving me a good target, and I didn’t wait. I leveled down on her and heard my second bullet thud against her skull. Again she flinched and humped from the impact, sagging without going off her feet. That was the only sign she gave that she was hurt. She didn’t bawl or slap at herself, and almost instantly she pulled herself together, stepped out of the brush, and came on at a rolling walk.

I hope I never live through another minute like that one, as I stood and watched her lumber toward me, step by step. I held the cocked Colt on her head, expecting her to come those last few feet in a sudden roaring rush. But instead she veered slightly and went by me a few paces away.

When she was directly in front of me she gave me the best target I had had. Her head was broadside to me then and I knew I could put a shot into her skull just below the ear. There was a chance of reaching the brain and ending the affair. It was a tempting gamble but the risk was pretty terrible. If I failed to kill her outright she’d be on me in a single lunge.

If she had swung her head to look at me, if she had stopped or even hesitated, I’d have shot. But she didn’t. She walked on as if she no longer knew I was there. My two shots, driven into her skull without actually penetrating the brain, must have dazed her temporarily. Save for my gun arm I didn’t move a muscle while she was in sight, and I can only suppose that she passed me after that second shot because she didn’t know where I was.

Read Next: Grizzly Hunting with a 6.5 Creedmoor

Back in the thicket again, she circled slowly toward the cubs. When she reached them there was another brief argument, with bawling and slapping and squalling. And now for the first time, crouched almost on my belly in the snow, I got a look at her family, which consisted of three good-size cubs.

I still did not dare to try getting into the tree. But after a minute the four bears started to move off up the mountain. They went very slowly. The old girl was having a hard time and the cubs were running around her in circles, puzzled and alarmed. When they got far enough away for me to move without attracting attention, I inched cautiously over to the tree and wormed my way in among the branches. And once I had the trunk in my hands it would have hustled a squirrel to keep out of my way!

Now I felt better. Beyond the spruce thicket the old bear was laboring a step at a time up the steep, snowy slope, with the three cubs in frantic attendance. I could see blood in the trail behind her, and she didn’t look around or pay any more attention to me. I was ready at last to finish her off and end the whole affair.

She was about twenty-five yards off and her broad back was an easy target. I squirmed into a comfortable position in a fork, laid the Colt across a branch, and let her have it between the shoulders. She spun half around, fell over backward, and rolled all the way to the foot of the slope.

That was a jubilant half minute. I had broken her back, killed a brownie with a handgun. Or so I thought. But I didn’t think so for long. She picked herself up and started to climb again, working painfully up the mountain toward the bench.

I had the gun cocked and the sights lined on her once more, when it occurred to me that I was throwing away a lot of ammunition considering my limited supply. A quick mental inventory told me I had nine shells left.

I was forty miles from home and — I now realized — in bear country. I might need those nine shells badly before I got back to the cabin on Kenai Lake. I was sure the bear would die anyway, so I decided I couldn’t afford another shot. But I’m still half sorry I made that decision.

I stayed in the tree for half an hour after the four bears had disappeared up on the bench. Then I climbed down, looked over the tracks and blood sign, and started after them. Probably it wasn’t very smart to trail that wounded brownie, but I still felt certain she was fatally wounded, and the more I thought about it the more I wanted her pelt to remember her by. It was a beauty.

I TOOK plenty of time. I went up on knolls to get a look at the trail ahead and I even climbed trees to scout out the country and make sure I wasn’t walking into an ambush. I followed the bears for a mile and a half, taking most of the afternoon to do it. Then I realized I had just about time enough to get back to my base camp before dark, so I gave up.

I was confident the bear would die in the night. The snow was settling and going fast, but there was enough left the next morning for tracking, so I left camp at daylight and went back to pick up her trail. It showed less and less blood sign and I was down finally to a small clot here and there on the snow or leaves.

Read Next: The Bear Gun Shootout: 10mm vs .44 Mag.

I stayed on the track until noon, following it another mile. By that time the snow was gone, and when the trail led down into an alder patch I gave up. I still believed she was dead and I still wanted her pelt, but not badly enough to follow her into the alders with a Colt!

Looking back on it, I’m not so sure she died after all. The clotted skeins of blood were few and far between where I lost the track at the edge of the alder patch. I hadn’t damaged her brain or she couldn’t have traveled that far. As for the shot that hit her in the back, I doubt it amounted to more than a deep flesh wound. The best guess, it seems likely, is that she had nothing worse than a bad headache for a week or two.

There are a lot of unsolved riddles about the whole affair. Did the bear notice me in the first place because of the commotion the squirrel made? Did she come after me because she was hunting, or because she resented my presence near her cubs — or just because she was looking for trouble? And having found me, when she broke out of the brush twice, why didn’t she keep coming and finish what she had started? And finally, when I hammered those two ineffective shots into her head, what kept her from doing what a wounded brownie is supposed to do?

I’ll never know the answers, of course. And nobody among the Alaska guides and hunters of my acquaintance claims to know them. But a neighbor of mine on Kenai Lake made one statement when I got home that I accepted at face value.

“You just weren’t born to be killed by a brown bear,” he said. “Or if you were, the day ain’t arrived yet!”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: The stirring adventure related by Cecil Rhode in “This Is It” stemmed directly from his work as a professional wildlife photographer in Alaska — and came near ending his career. That career had its beginnings back in 1933. Up to that time Rhode had lived in Oregon, Kansas, and California, spending a great deal of his time in the outdoors. While prospecting for gold one summer in the Sierra Nevadas (and trout fishing on the side) he met an old sourdough who described the glories of Alaska. Rhode decided to have a look at it, via a float trip on the Yukon River. He went, he saw — and he’s lived in Alaska ever since. He makes his headquarters in a cabin near Moose Pass on the Kenai Peninsula. Using it as a base, he has hunted (with rifle or camera) all the big game of the north except the polar bear.

This story first ran under the title “This Is It” in the August 1952 issue of Outdoor Life.