I traveled from my home in Minnesota to Nebraska to photograph a young bowyer named Correy Hawk, whom on the internet I’d seen make some beautiful old-school primitive equipment under the moniker of “Organic Archery”. I liked his pictures, which depict longbows and wood arrows, all handmade, old-school style, but I never thought the story would get personal. It did.

Here’s why. The first 29 deer I took with arrows flew from store-bought wooden and fiberglass longbows and recurves. I took some deer at 10, 20, and 30 yards, and a number of them I arrowed at distances closer than that. I shot one deer while wearing all white on a riverbed in western Minnesota during a snowstorm. That deer took my arrow at five yards. Those are memories I’ll never forget.

In years since, through my job as an outdoor photographer, I got enamored with the new technology of carbon, strings, cables and sights, and marveled at my ability to take an animal at 89 yards, which I accomplished along the Cheyenne River in South Dakota.

Then I sat and listened to Correy Hawk talk about why he spends his days splitting staves out of the trunks of big old hardwoods (Osage Orange, Hackberry and others) on nearby Nebraska farm ground. Those staves stay stacked along the north wall of his modest shop. When they dry sufficiently, he pulls his drawknife hundreds of times over a stave until a longbow reveals itself. It’s ancient art.

And once that artistry hit the palm of my hand, I was transported back in time. I felt like a supremely confident 20-year-old, pre-historic archer ready to do battle with a mastodon. Of course, the one available bow in the whole shop fit me perfectly. It was destined to follow me home.

“The wooden bow is the spirit of archery,” Hawk says. “It’s been with us for thousands of years. It’s no doubt that when you hunt with a primitive weapon you have to learn the art of woodsmanship. There’s no way you can shoot an animal from great distances. You have to be able to get very close to that animal. And when you hunt with a primitive bow, that happens often. The first animal I killed with [my own] hand-crafted equipment was a whitetail doe at about ten yards. It was early season, still warm, and I was in light flannel shirt, sitting on ground. My preferred method.”

A Trad Bow Renaissance

Hawk is an old-school kind of guy. He’s a digital minimalist, craftsman, and US Marine Corps combat veteran. He makes his bows, crafts his arrows, teaches survival skills, and shares his knowledge easily and freely.

When he got home from military duty in Afghanistan, he found himself in search of an artistic outlet and was looking for a therapeutic and artistic relief from stress. He bought a recurve bow, and made some arrows. Soon he researched and taught himself to make longbows. He started with dimensional lumber from the hardware store, and then learned to fell trees to make staves, from which his longbows are born.

Hawk makes plenty of bows to order himself, and he brings in small groups of people who want to craft their own bow under his tutelage.

“There seems to be a shifting of the tides, where there’s a reality that modern archery has been tech-ed to death. There’s a new thing every year. The old bows become obsolete the next year, and then there is a new thing the next year making the new product look better in some way.

“It seems to me people are feeling a pull toward the old ways, handcrafted and locally sourced. You also see it in the farm to table movement,” Hawk says.

One Bow at a Time

Hawk’s strong hands clamp a six-foot stave of Osage Orange onto a pedestal that’s firmly anchored to a concrete garage floor. A wicked-sharp draw knife goes rhythmically to work, shaving off outer bark, then thin layers of wood. The shavings lay in a heap on the concrete floor as the ancient tool is rhythmically pulled, and pulled again, toward the artists’ chest.

There’s a longbow residing inside that stave of wood, and Hawk aims to find it. When he’s done, that stave will be transformed from the rough-cut trunk of a tree into an artistic treasure, and a hunting tool that will last a lifetime — or longer.

The first thing he teaches in his bow-making classes is tree identification. He focuses on hardwoods, which grow all over the country. No pines, conifers, or cottonwoods need apply. Hawk teaches students to figure out the trees’ identification, then learn its specific gravity, and they then fell a six-foot section of a lower trunk that is unobstructed by branches. He teaches them to use a wedge to spit it into quarters, or if it’s really big, into eighths. Then his students mill that piece into a bow stave. That stave needs to season for about a year until the wood has a low moisture content, he says. A green bow can’t handle the extreme bending of a bow’s arc without problems.

Hawk knows some seasoning tricks that can hasten the drying process in as little as 30 days. He keeps lots of staves stacked against his garage wall for classes and future orders.

A stave gets the draw-knife treatment in the beginning to form a bow blank. Attention is paid to each trees’ unique character, especially its’ knots and natural grain.

“The grain flows like a river,” Hawk says. “You have to follow that grain faithfully, and if you don’t, your bow might break. If you fail to follow the grain—and violate the grain—you’ll shorten the life of the weapon.”

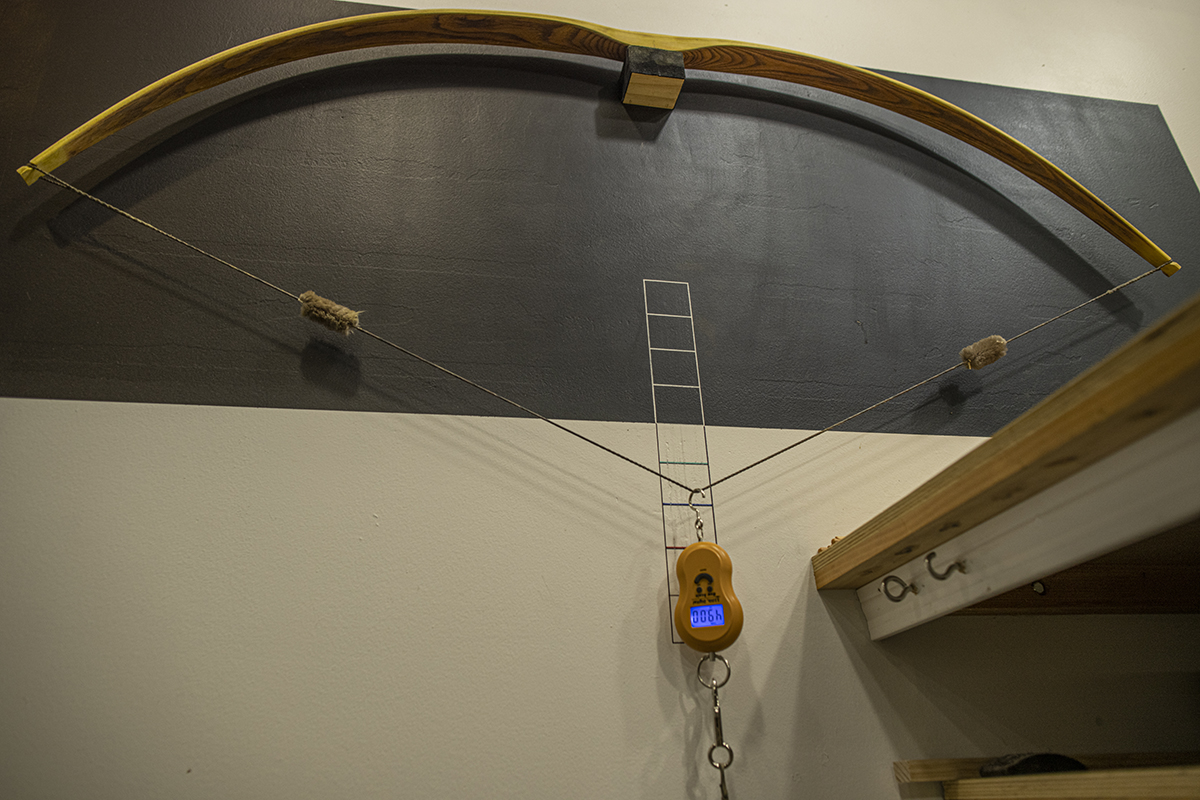

“Tillering is the meat and potatoes of bow making,” he said. “You can make a functional weapon out of almost any tree or sapling with the systematic removal of wood – by leaving wood on weaker areas, removing from strong areas, then exercise the bow with a pulley system to create a beautiful even arc – constantly checking the draw weight. If draw weight is too heavy, you remove wood, too light, you get to start over,” he laughs.

Then the real fun begins. After tillering, Hawk makes a proper bow string and then test shoots the bow.

“We’re looking for a powerful feeling weapon. You’ll know right away if it shoots an arrow in a flat-laser-like trajectory. If so, you have a hunt-worthy bow,” he says.

Hawk noted that a properly built bow can easily rival the power of a modern fiberglass bow.

“I like to see if it’s smooth and fast, then sand down the bow and add to its finish with steel wool,” Hawk says. “I then seal the bow with six coats of penetrating oil, tallow, and a beeswax mixture to finish it off.”

Walking the Walk

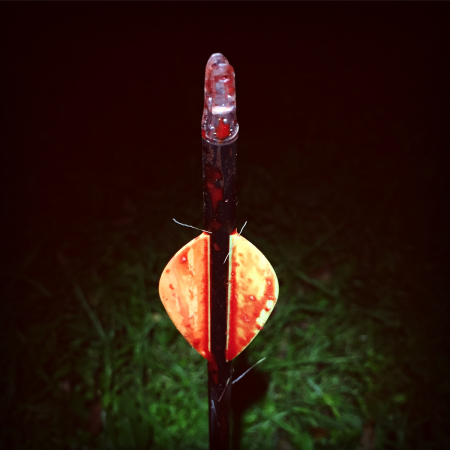

Watching Hawk shoot a primitive longbow made by his own hand looks much different than watching a compound bow shooter. Hawk rapid-fires arrow after arrow into a bullseye that’s 20 yards away on his back yard range. The custom wooden arrows stack up one next to the each other, wild turkey feathers nestling together. He reaches over his back, time and again, pulling arrows from quiver to string, the shafts finding their mark. His rhythm mirroring the speed of a revolver being thumb cocked at each shot. It’s primitive beauty.

When I get home, I hang the Hackberry bow that Hawk made on wood pegs on my wall. I call it, simply, “Hack.” As for my own shooting, it’s getting better every day as my muscles respond to the repetition. Before too long, dandelion heads are being snapped off by my arrows, one after the other on the hill behind my house.

I can’t wait until it’s time for me and “Hack” go make meat.