Editor’s note: The two authors decided to put some long-held beliefs about deer movement to the test after hearing their friend, who is a lifelong hunter, talk about how deer react to weather. Both authors are scientists and conducted a field experiment using their expertise, trail cameras, and weather data. Below you can read an overview of their study and their findings, which we think will be interesting to every deer hunter in America, even if it’s not necessarily applicable to your corner of whitetail country.

There have been a few studies conducted on the alleged effects of meteorological and astronomical events on deer movement, but the vast majority of them have been conducted in the southern United States. We used four Victure Mini Gamer Cameras, placed around a two-acre property in the rural village of Effort, Pennsylvania. The study was conducted in a community setting where there is a local estimated population of about 20 deer. There are vast areas of forest and state game lands approximately two miles (3.2 kilometers) away. The cameras were not baited and placed in areas where game trails were present and deer scat was commonly seen. Two of the cameras were placed near occupied homes and two were placed in heavily forested areas. The image below shows the four areas captured by the game cameras.

The cameras collected images of deer movement for 12 months (February 18, 2020 to February 19, 2021). Meteorological conditions, such as temperature, wind, barometric pressure, and precipitation were retrieved from Weather Undergrounds data from the nearest airport, Lehigh Valley International Airport. Astronomical data, such as the percent of the moon illuminated was retrieved from NASA’s Horizon data base. For the purpose of this study, only the percent of the moon illuminated was used and does not factor in waxing and waning conditions.

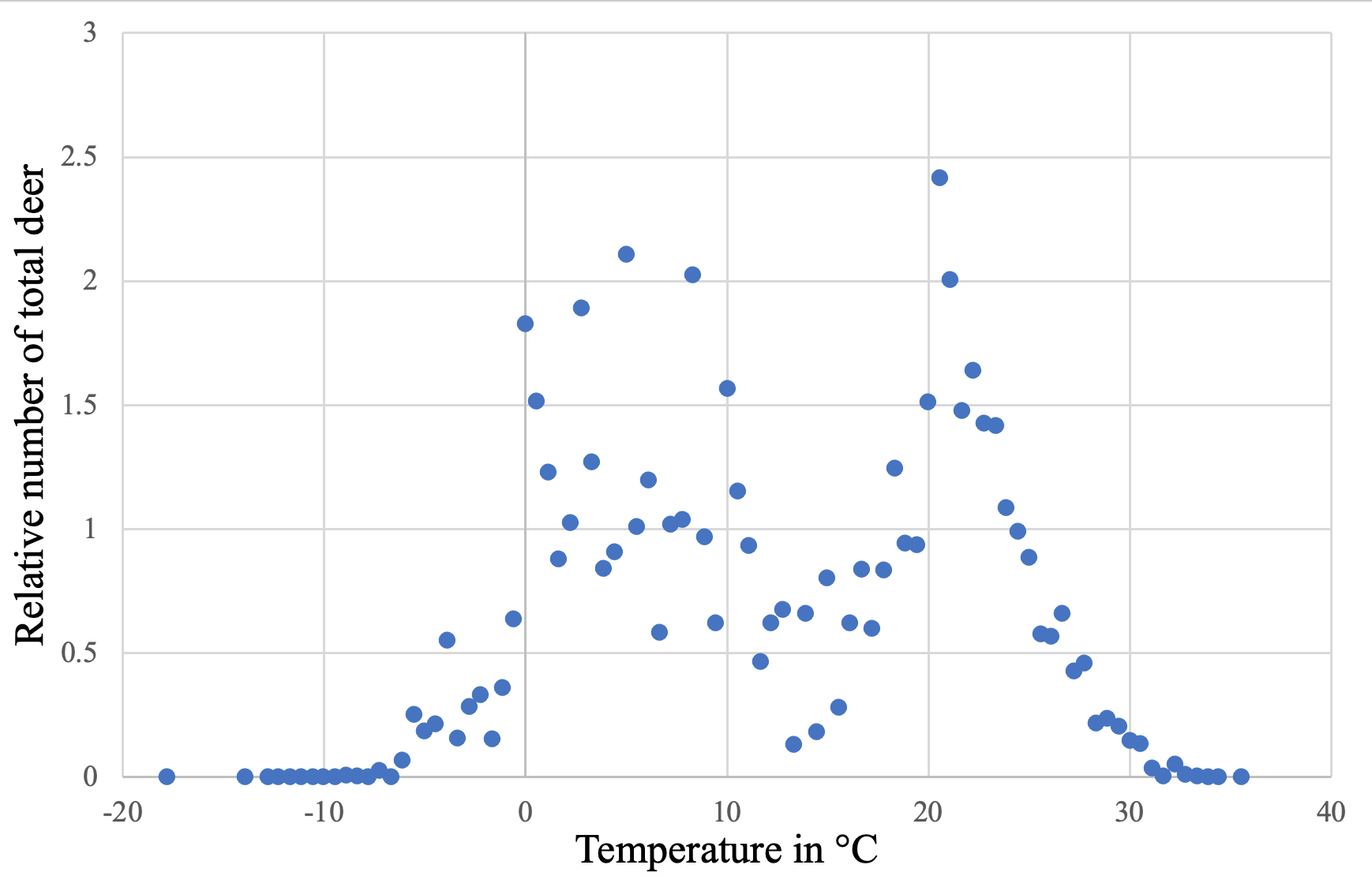

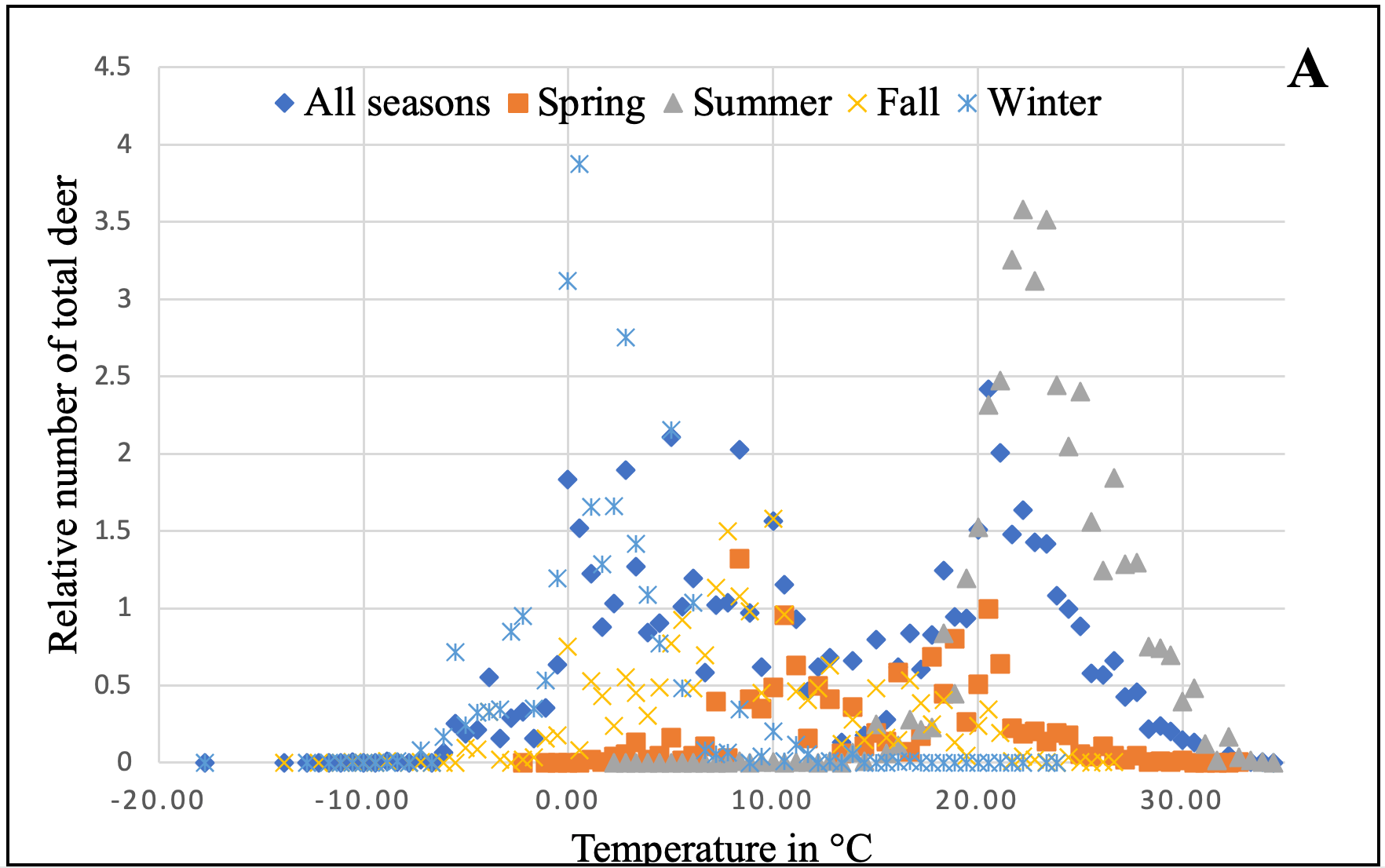

We analyzed each weather variable individually. One of the many myths surrounding deer hunting is that deer do not move during days with warmer temperatures. Our analyses support this myth. We found that two peaks of preferred temperatures seen below.

The first peak is found around colder temperatures (0-10ºC, or 32-50ºF) which corresponds to mostly fall and winter months. The second peak was during milder temperatures (about 20ºC, or 68ºF) and corresponds to summer months (Figure 3A). We also analyzed the movement in relationship to the rut and fawning. We found that the peak of movement at 50ºF (10ºC, or the second peak) coincided with fawning time (below).

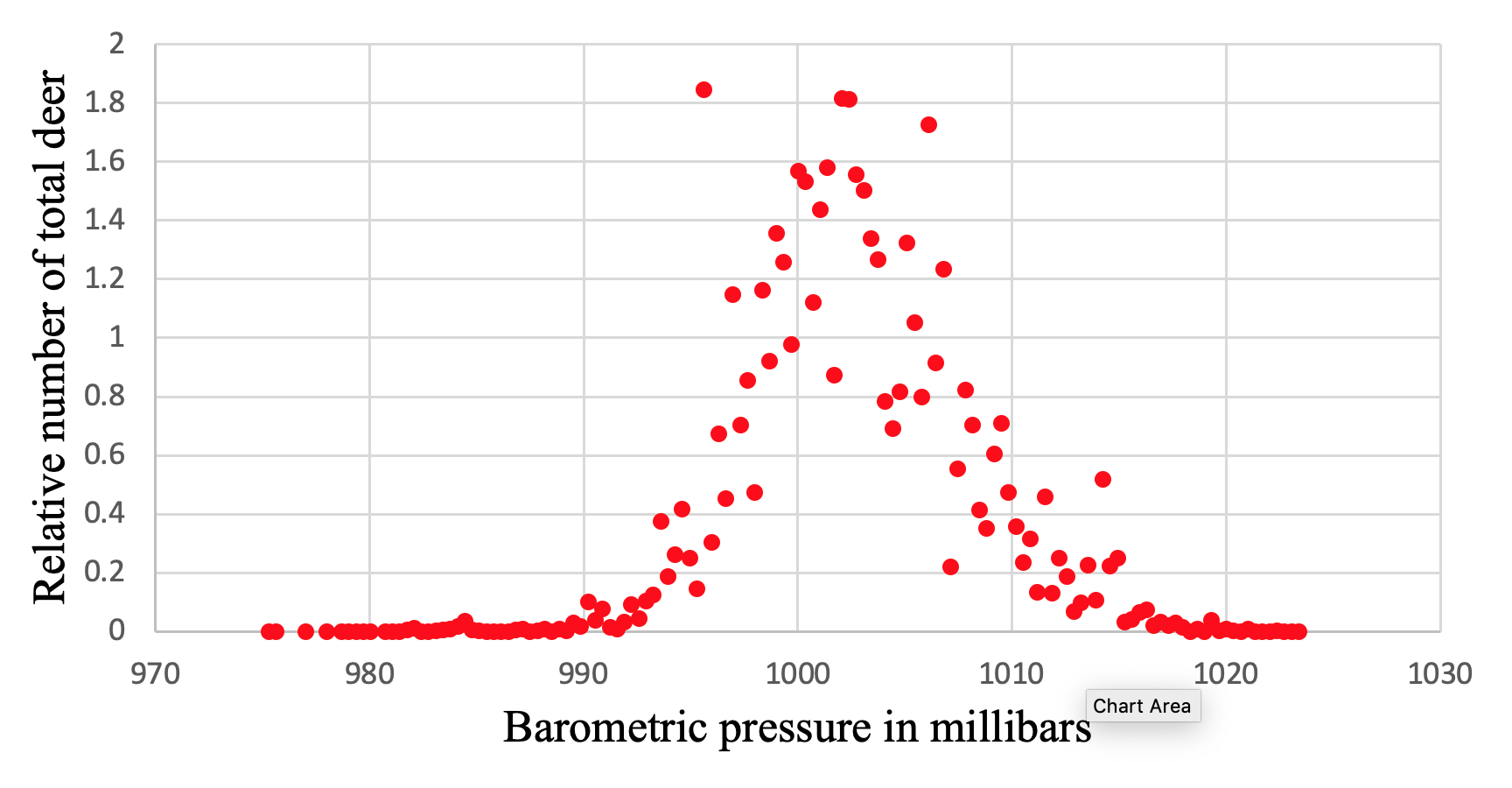

The next weather variable we analyzed was barometric pressure. We found that deer were most likely to move at a barometric pressure of approximately 1001.36 millibars (approximately 29.57 inches of mercury) which is just below average pressure (below).

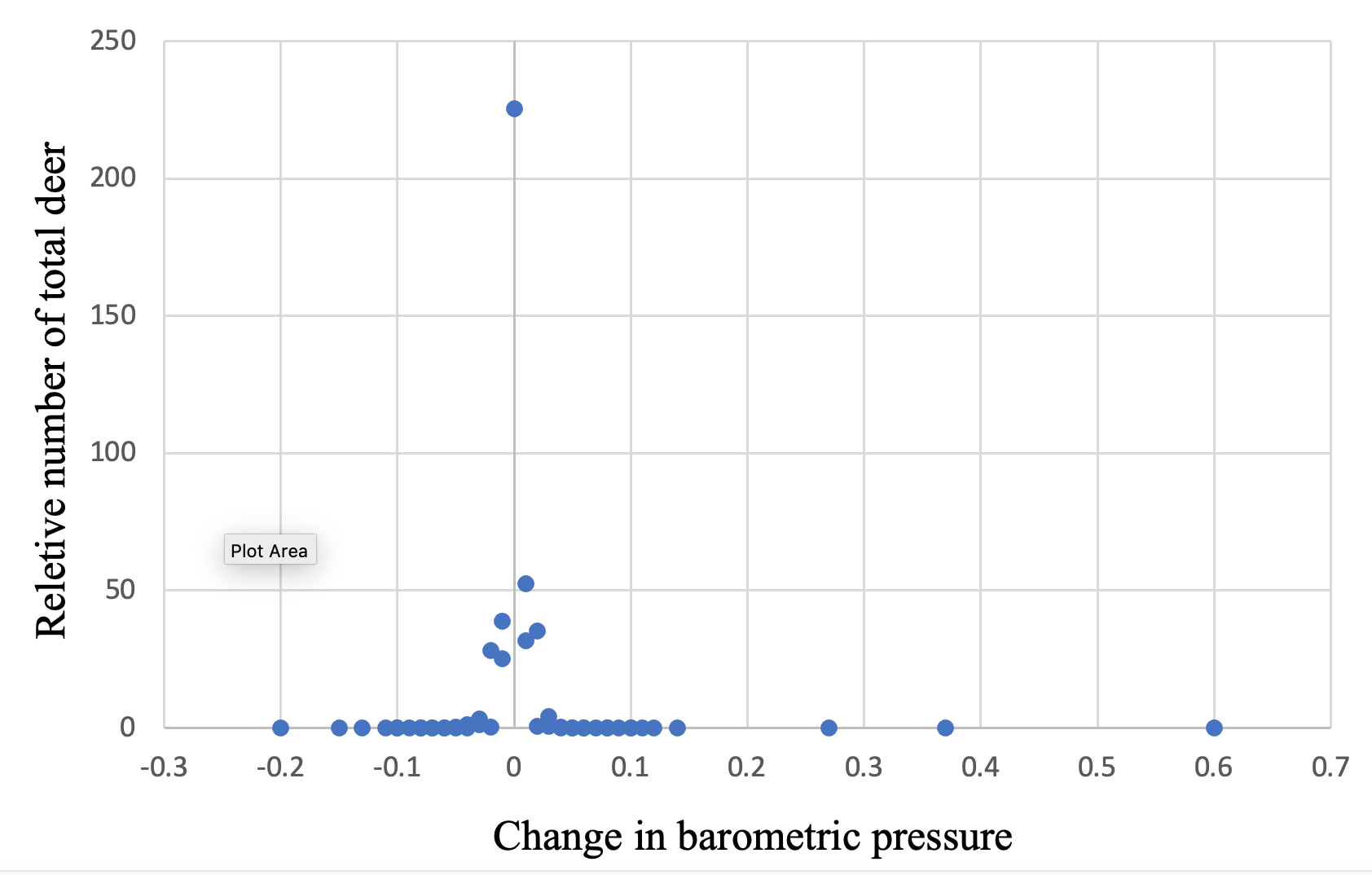

We also analyzed whether deer were affected by changing barometric pressure. We found that deer were more likely to move at lower pressure changes, and contrary to some myths, it did not matter if pressure was increasing or decreasing. The graphical analysis can be seen below.

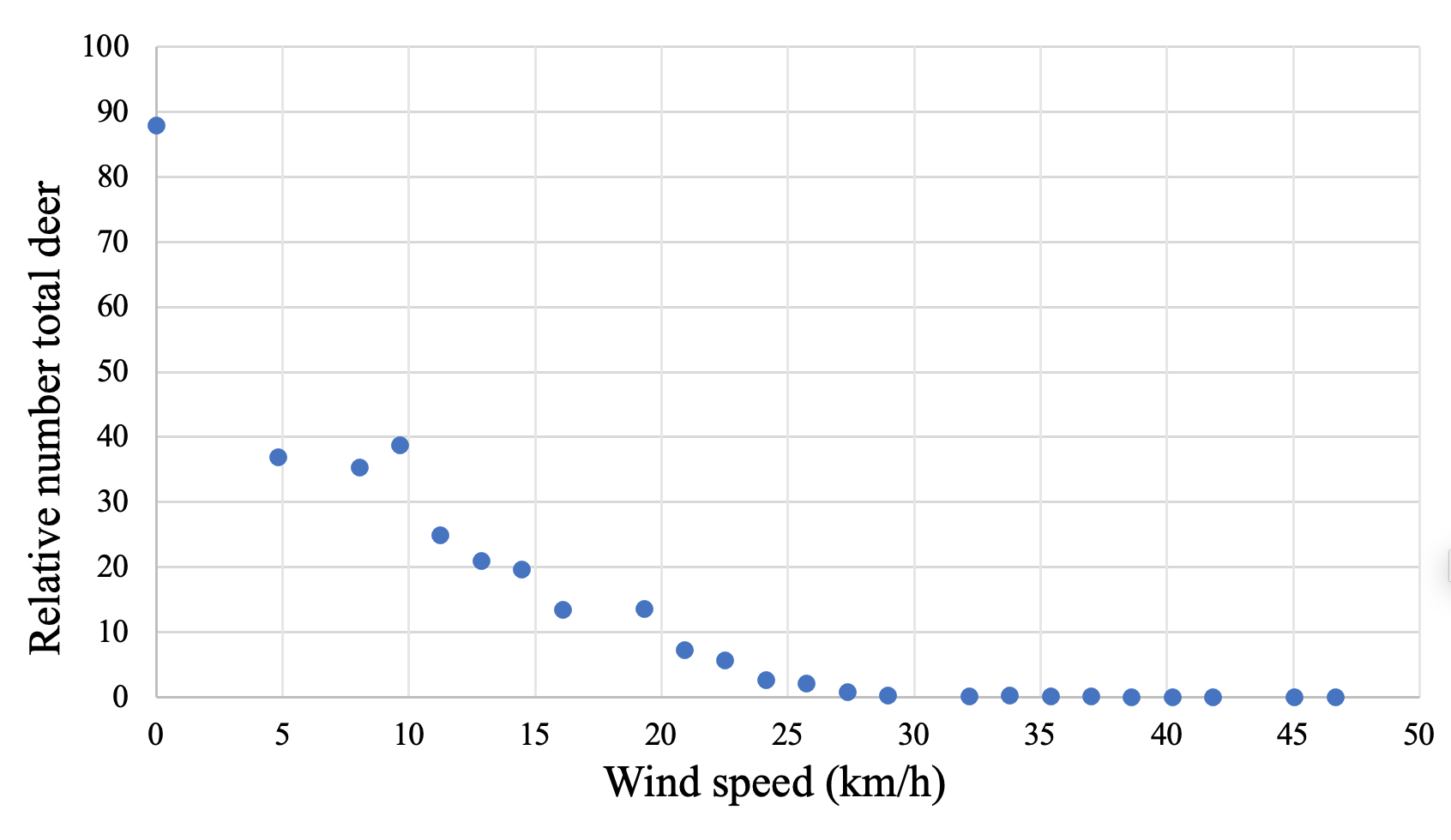

Our study found that as wind speeds increase, deer movement decreases. Deer were more likely to move during calm conditions. They would move at wind speeds from 3.1 – 6.2 mph (5-10 km/h) but as wind speeds increased from there, deer movement decreased (see below).

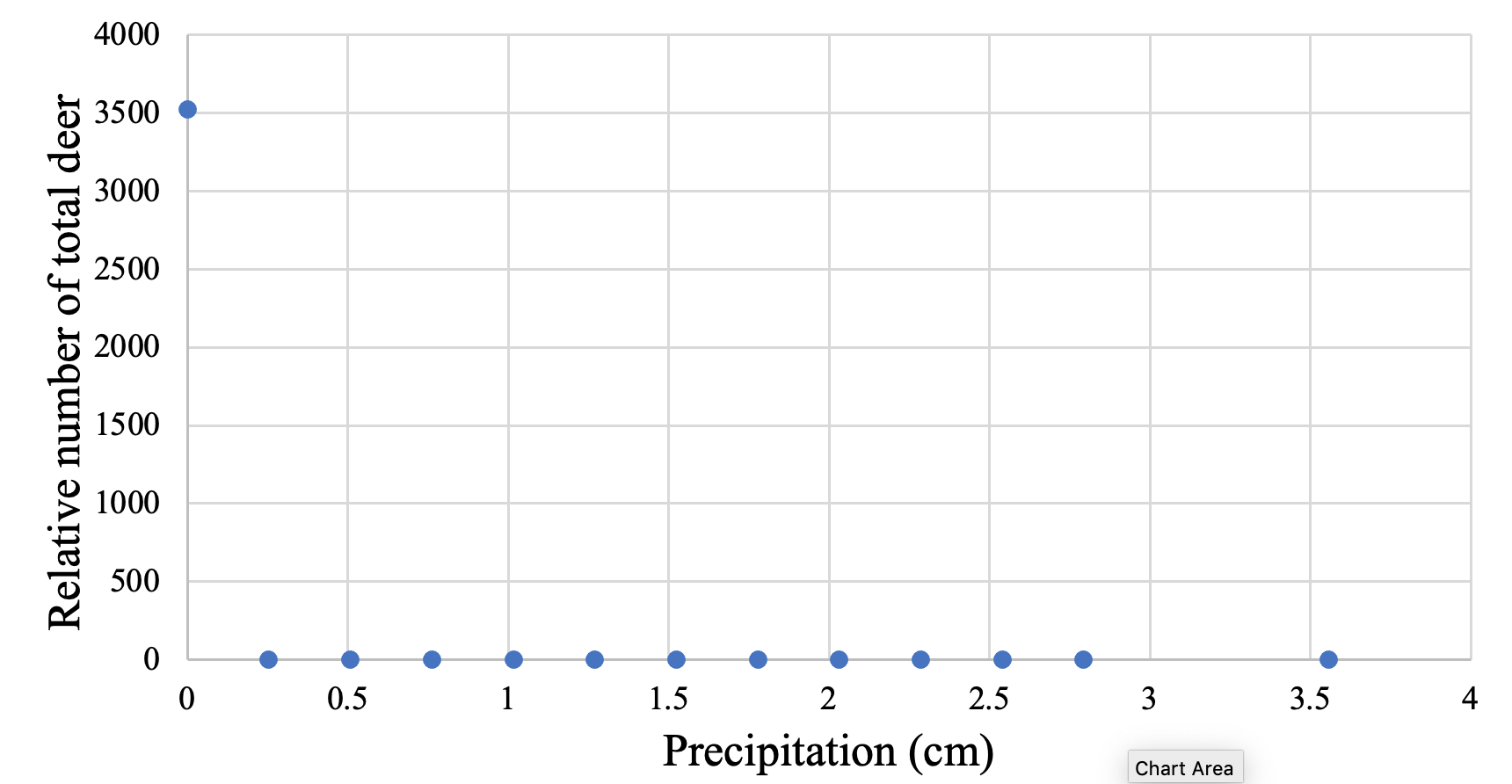

Another hunting myth is that rain can function as sound camouflage for deer, and therefore deer are more likely to move with a light rain. However, our study did not support this myth and, instead, found that deer are most likely to move when there is no rain. They seem to stop moving when there is rainfall (below).

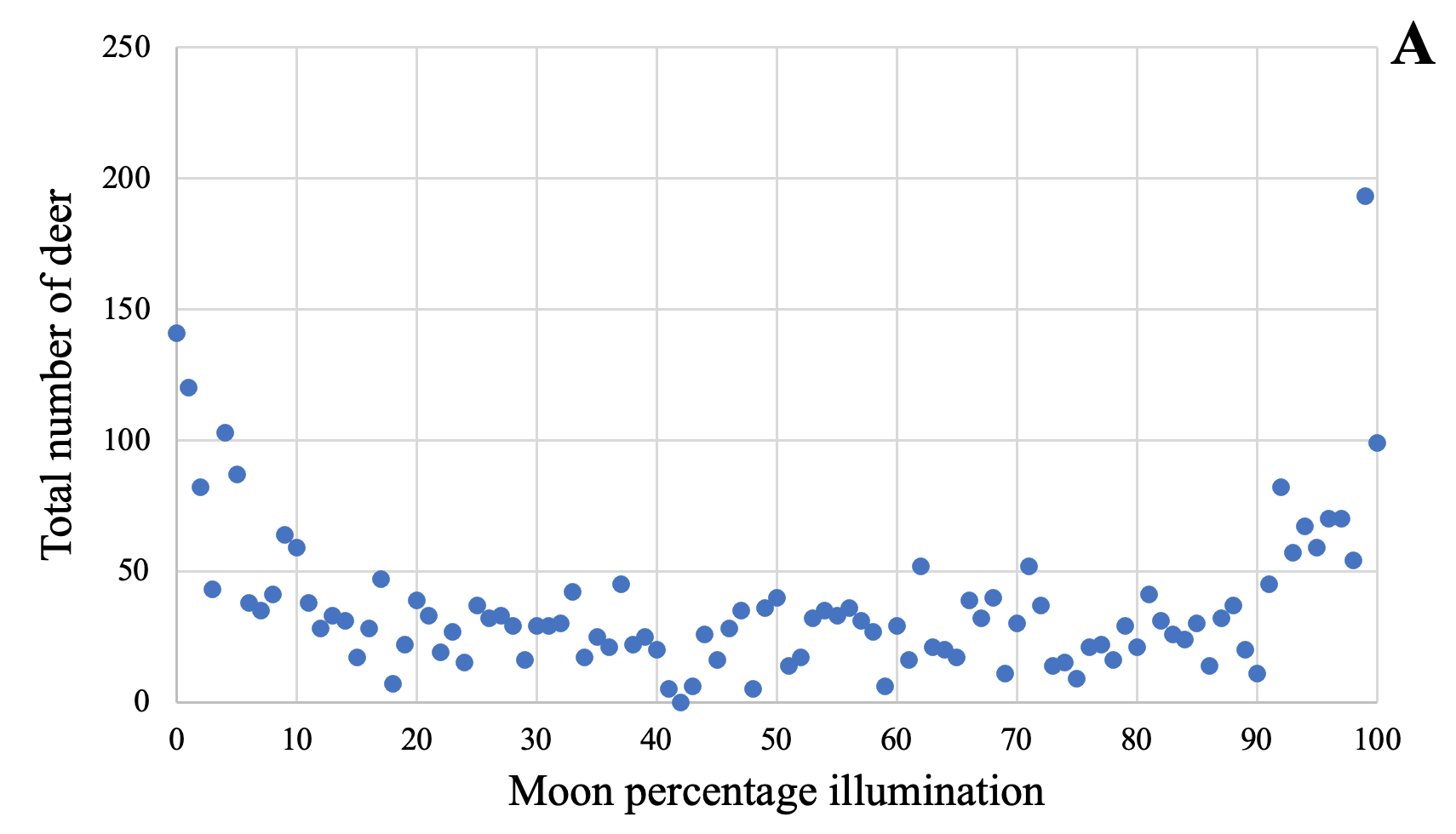

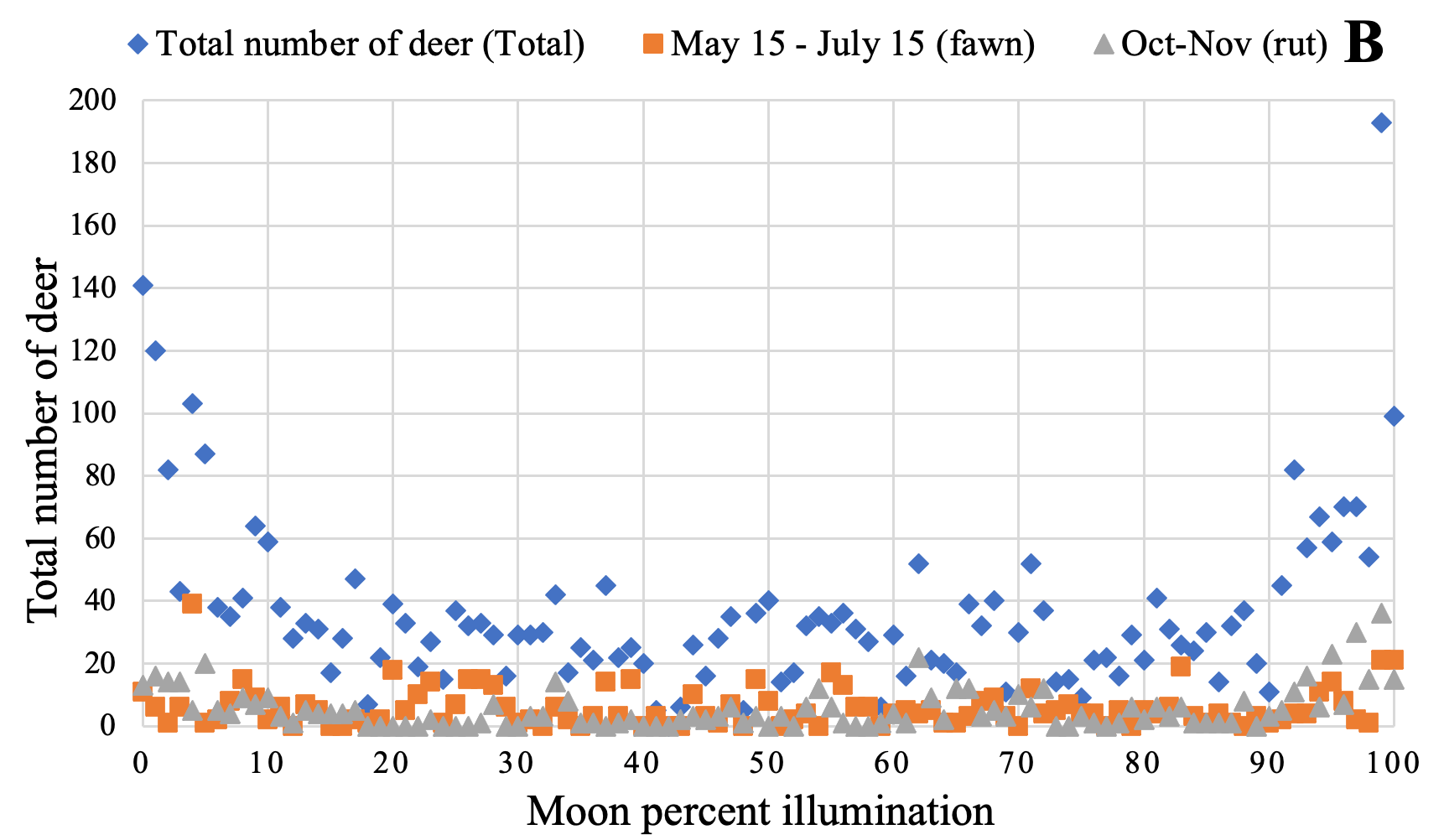

It seems that one of the most prevalent myths surrounding deer movement is the moon phase. There have been many studies that did not find a correlation between the phase of the moon and deer movement. Our study, however, found that deer movement increased at a new moon (little to no moonlight) and a full moon (the most moonlight) (below, chart A). One concern of this study was that a full moon occurred twice during the rut. To ensure this was not influencing the movement peak we saw at the full moon, we analyzed deer captures and the moon phases of movement during fawning and the rut (below, chart B). However, the graphical analyses do not show the rut having an important impact on the number of instances captured on the full or new moon.

Our study supported the hunting myths that deer prefer to move during mild temperatures, at slightly under normal barometric pressure, as well as during new and full moon. Our study did not support that deer were more likely to move with increasing precipitation or wind. We must emphasize that this study took place in the northeast and may not apply to other regions of the USA. Also, we do not know why deer seem to move more during some astronomical conditions. If you want a copy of our full study, please email us or read about it here.