I’d forgotten what hanging elk meat smelled like, but within seconds of the sharp aroma from the walk-in cooler hitting my nose, I was flooded with memories. I remembered standing in an old potato cellar, smelling the aging meat of a bull elk my dad had killed. It must have been nearly 30 years ago, but I instantly recognized the smell.

It brought back many memories of hunting elk with my dad when I was a youngster. I’m sure I was more impediment than hunting partner—we never did get an elk when I was along—but he usually brought me anyway. I spent many quiet mornings in southern Colorado eagerly waiting for a big bull to show up. We bowhunted most of the time, predominantly on public land. Despite the lack of success, or maybe because of it, those early hunts were full of important lessons. To this day, while walking quietly down a trail, I smile at the memory of being scolded for dragging my feet, kicking rocks, and making all sorts of other noises that a kid will produce when hunting with his dad.

I found plenty of hunting success after I moved from Colorado to Alaska at age 16, and it didn’t take long for elk hunting to drop off my radar. After 20 years in Alaska, I had yet to hunt big game in the lower 48 as an adult, so the irony wasn’t lost on me when I was invited for five days of elk hunting in northern New Mexico with the crew from Barnes Bullets, about an hour from where I grew up hunting in Colorado. We would be hunting on private land, at the Quinlan Ranch, and although I’m not accustomed to doing guided hunts, I was excited at the opportunity to experience some new country that was so close to my old home, hopefully with better results.

Elevation

“Tails,” I called.

Tails it was, as the pillow of dust settled back around the quarter in the two-track we stood on. Our headlamps showed that I had guessed correctly and would have first choice on a shot opportunity that morning. I was partnered to hunt with Brady Miller, who works for GoHunt, and our guide “Moggs,” whose elk-guiding experience far out paces his 23 years of age. Moggs has been guiding multiple elk hunters every year since he was 17. He told us that he’s finally old enough that hunters don’t look at him sideways when they find out he’s their guide. Brady and I were happy to get the youngest guide on the crew. We figured that he would be willing to walk a lot, and I was eager to learn from him. That first morning, I stepped into the woods with the same pre-dawn anticipation I had as a kid.

As daylight broke, we walked quietly along the gradually inclining two-track. We took our time, moving through the timber and carefully watching the draws and meadows for elk. Our morning strategy would be to walk and still hunt, hoping to catch bulls moving from their nocturnal feeding areas in the lower country, back into the thick timber to bed. Our walk wasn’t difficult, but the thin air at 9,500 feet kept me embarrassingly out-of-breath. Living at an elevation of around 800 feet, I needed more oxygen than my lungs could pull from the air, and I was worried that I’d be sucking wind too hard to make a shot that would certainly need to be taken quickly. In such close quarters, it would be tough to get a good look at a bull, decide to shoot him, and make a good shot. The whole process would need to happen in a matter of seconds.

Then we saw them.

The two bulls saw or heard us at the same time we saw them, about 75 yards away. The first was a young five-by-five, who sprinted up through the timber. A larger bull followed him in a flash. Before we could do anything, they were gone. We could only hear their antlers clacking through the timber farther up the ridge. The road continued to wind uphill, and we heard a twig snap as we crested a hill about 15 minutes later. To our right, one of the two bulls walked down and out of sight as the other one moved through the timber. It was the bigger bull, a six-by-six, but we had no time to even set up for a shot. He was gone.

No Rags Allowed

Our days in camp consisted of a pre-dawn departure, with a few hours of walking and still hunting, a return to camp for breakfast, a nap, lunch, then sitting in blinds overlooking meadows and water sources in the evening. To some, sitting in one spot all afternoon and evening might cause anxiety from not knowing what’s over the next ridgeline, but my lungs appreciated the break. Brady, Moggs, our photographer Nick, and I packed into a small blind mid-afternoon, hoping a big bull would show himself.

“No rags allowed,”Moggs said (meaning rag-horn or small branch-antlered bulls). We fired endless questions and speculations about the quality of bulls that we were looking for—and could realistically hope to see. In less than a day of questions, we had all figured out that our guide was an easy-going guy, and we all shared a similar, somewhat irreverent sense of humor. Moggs wasn’t going to let us shoot any little bulls, and I was good with that mandate. Although I had never killed an elk, I wanted to make the most of the opportunity.

The daylight hours passed quickly as we joked and spun yarns, but we all got serious as the sun began to sink low. As the air chilled and the shadows lengthened, the chatter died down and we became silent. We heard them first, the clatter of hooves on rocks. In an instant, a stream of elk poured down from the timber, through a patch of oak brush, and into the meadow we were watching. At the rear, came a single light-colored bull.

“Too small, he’s a five,” Moggs quickly stated. The elk milled around at about 250 yards and our hopes of a bigger bull appearing were dashed when shooting light expired and the herd was enveloped in darkness.

We stopped by the barn, on the way to camp to find that two more hunters had killed bulls that evening. Two had killed bulls in the morning, leaving four more tags to fill. Everyone exchanged stories, admiring the bulls and taking in the smell of fresh meat being hung in the cooler.

No Snow

We were hunting in an area that has a reputation for fantastic elk hunting. It sits on a primary migration corridor through which elk move out of the mountains in southern Colorado toward their wintering grounds. As any experienced late-season elk hunter will tell you though, it usually takes heavy snow to get them on their way. We had none.

I didn’t pay much mind to the lack of snow. On day two, it was Brady’s turn to have first choice, and we walked through about 3 miles of broken timber and oak-brush hills. Aside from one strong whiff of elk, we turned up nothing. Still, we were enjoying ourselves. We were even encouraged in hearing that another hunter had killed a bull, and we essentially had 3 more days to hunt with nearly the whole place to ourselves.

After the evening hunt, which produced about 75 cows, a few rag-horns, and a couple of five-by-five bulls that we passed, the guides offered to split us up the following day. So the next morning and evening Moggs and I hunted hard but didn’t see a single elk. It’s easy to be pleased when you don’t bring any expectations to the table, and I was enjoying hunting longer than I’d have gotten to had I killed a bull the first day. I began to get the impression, however, that the optimism of the guides might be waning.

I’ve worked for a couple outfitters as an assistant guide here in Alaska and I knew the exact conversation that I was overhearing as I walked by the guides’ dinner table that night.

“We need snow…”

“We’ve got what we’ve got…”

“I can’t believe we didn’t see anything there…”

I’d certainly had a couple of shot opportunities, but I wasn’t turning down bulls left and right. Hunting is hunting, and nothing is guaranteed, but I still felt confident that if I hung in there, I’d get a chance at a nice bull.

Surely there’s one or two respectable bulls still hanging around, I told myself to stave off the seeds of doubt that the guides’ conversation had planted.

In an Instant

As more hunters punched their tags, the 5 a.m. coffee crew became a little scarcer. By the fourth morning, only three of us still had tags, and the bustling dining room was quiet. Brady and I would split up to hunt separately again, but in nearby areas. He and his guide went to a spot where they had seen some bulls—including a thin-antlered six-by-six—the day before.

Moggs and I would walk a two-track that ran atop a ridgeline and marked the boundary between the ranch and a piece of public land where the elk moved to bed. As we’d done before, we would try to intercept bulls moving up through the draws and meadows before they crossed onto the public land (that we weren’t allowed to hunt). The slight breeze was favorable, and the fine dust on the two-track made for silent walking. A fiery sunrise to the East made me pause for a moment in admiration.

We covered ground quickly and quietly, carefully picking apart the timber and brushy meadows on our left, with bare fenceposts that marked the property boundary on our right. We crested one hill and Moggs froze. A bull was moving up through the draw below us, about a hundred yards away. He was a five-by-five, so we watched as he meandered up the hill, noticing us right before crossing the fence line with a hop. Down to the left, even closer, appeared another bull, but he was even younger. We waited motionless as he followed the path of the other bull, cresting the hill and dropping into the timber.

A few hundred yards further, we came to another opening, and Moggs set up his shooting sticks as we saw the hind ends of two bulls go into the brush across the small valley.

“There’s three of them,”he said, as I saw the third bull’s front-end sticking out from behind a jumble of brush. He was looking right at us. We hadn’t gotten a good look at any of the bulls, and as I looked at this one, he looked narrow with a dark backdrop of shadows and pine, about two hundred yards away.

“Too small, he’s a five-by-two.”

I thought, hoping for a better look at the others. We stood like that for several seconds, then Moggs and I simultaneously gasped as he turned his head. I saw his antlers spilling back and didn’t have to count points to know that this was a bull I should shoot. I’m not sure if I said that I was going to shoot him first, if Moggs said I should shoot him first, or if we said it at the same time. He was about 200 yards away, but only 75 yards from the fence line, and he surely wasn’t going to stay there for long. Having already put a round in the chamber, I clicked the safety off and fired.

In the instant after the shot, I listened for the “whomp” sound that a .300 Win. Mag. bullet makes upon hitting a big game animal, but I heard nothing. He took off running to the right as I quickly cycled the bolt and got back on the scope. I pivoted the rifle on the shooting sticks, and as soon as the crosshairs swung in front of the brown hair at the front of his chest, I broke the shot. The bull’s hind legs went out from under him and he piled into the ground. Not sure where my second shot connected, we hurried over to him.

“Do you think I missed that first shot? He sure didn’t act hit,” I said to Moggs as we closed the distance.

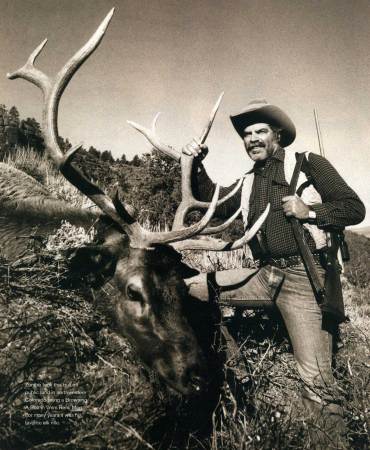

The bull didn’t move. He had gone down with his nose on the two-track, just a few yards from the property boundary, and in a position to be loaded right into the truck. My grandpa would have been proud at that. I quickly saw that both of my shots had hit the bull in the lungs, slightly high, but only about six inches apart.

Read Next: Cape Fear: Hunting Buffalo in the Matetsi Safari Area of Zimbabwe

I thought about the many memories from my childhood that had been almost forgotten. I took a minute to soak up the experience of taking my first bull elk. Moments like that don’t last long, and despite all the mornings of anticipation in my childhood, and the years that the dream of getting a big bull elk were dormant, it was over before I could fully process it. After leaving camp, I spent a night at my aunt’s house, in the tiny Colorado town that I grew up in, and before dawn, on the way to catch an early flight, I had her drive me by the old cellar where my dad used to hang his elk. This hunt hadn’t only given me new memories, it unlocked lots of old ones as well.