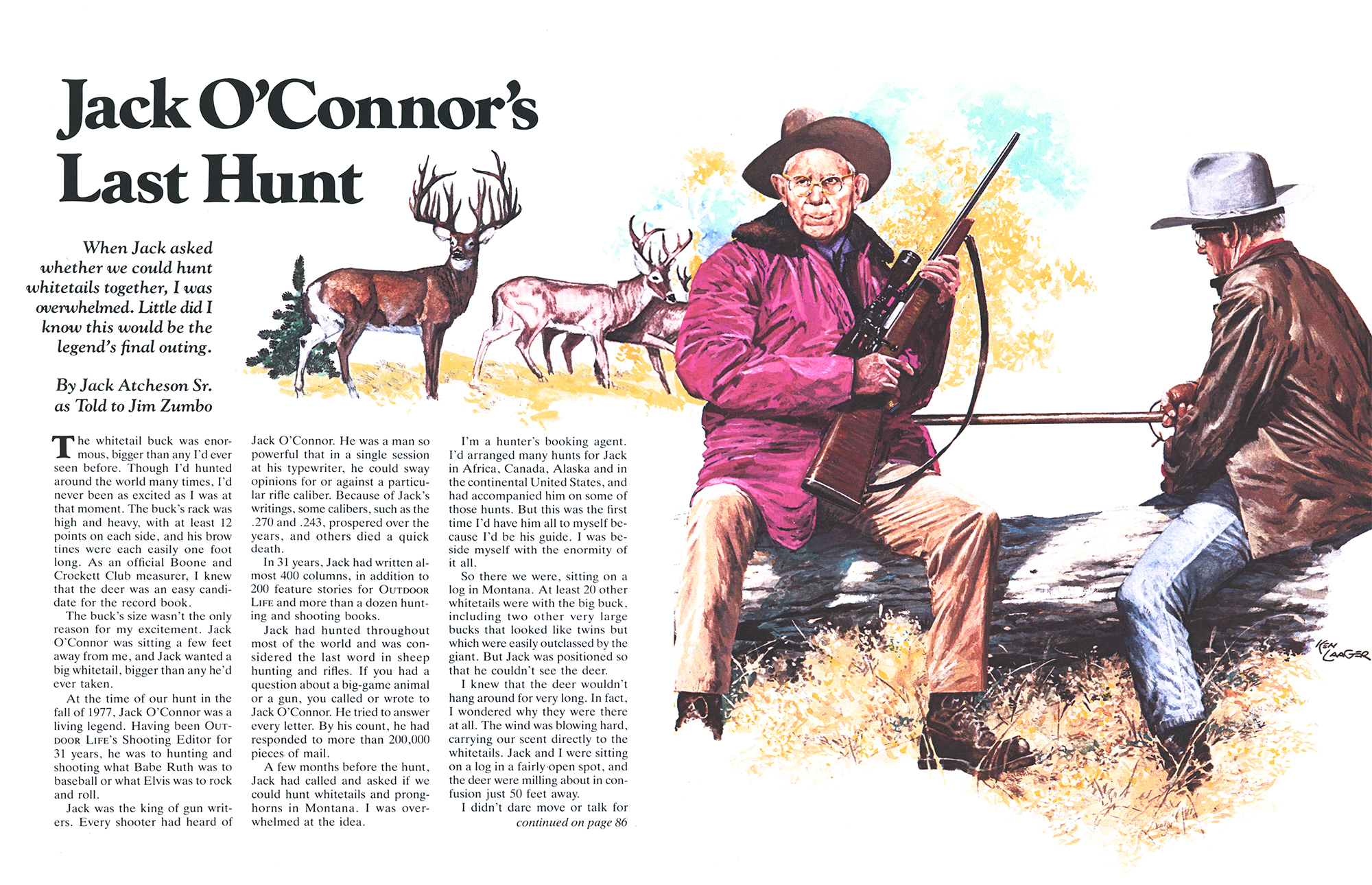

THE WHITETAIL BUCK was enormous, bigger than any I’d ever seen before. Though I’d hunted around the world many times, I’d never been as excited as I was at that moment. The buck’s rack was high and heavy, with at least 12 points on each side, and his brow tines were each easily one foot long. As an official Boone and Crockett Club measurer, I knew that the deer was an easy candidate for the record book.

The buck’s size wasn’t the only reason for my excitement. Jack O’Connor was sitting a few feet away from me, and Jack wanted a big whitetail, bigger than any he’d ever taken.

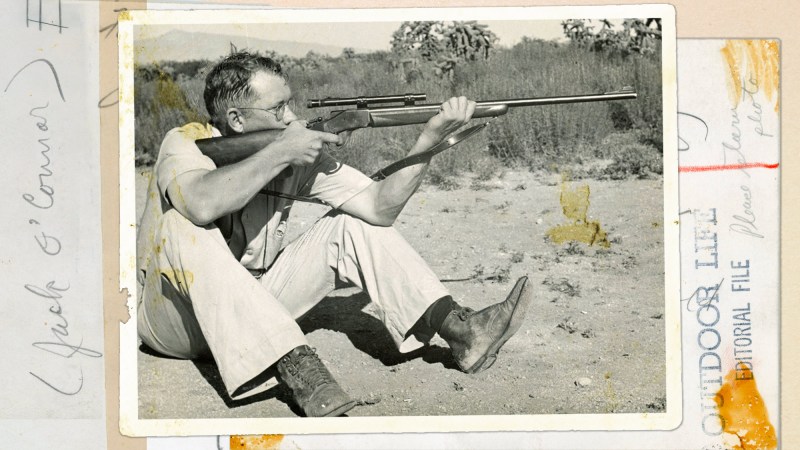

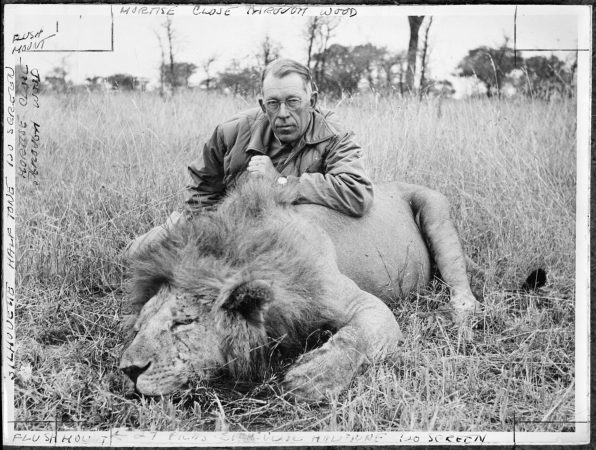

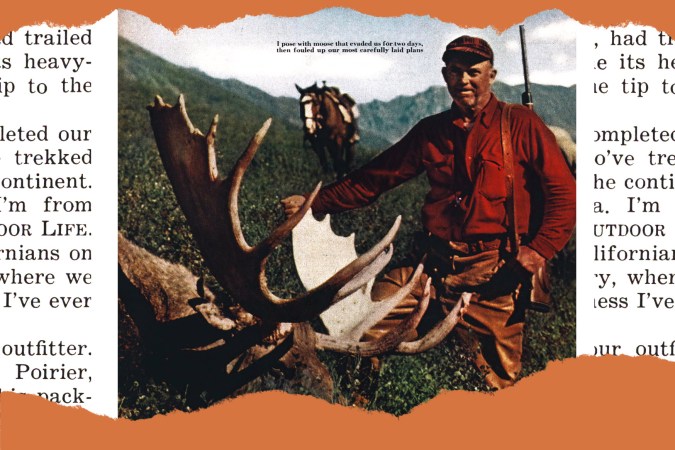

At the time of our hunt, in the fall of 1977, Jack O’Connor was a living legend. Having been Outdoor Life’s Shooting Editor for 31 years, he was to hunting and shooting what Babe Ruth was to baseball or what Elvis was to rock and roll.

Jack was the king of gun writers. Every shooter had heard of Jack O’Connor. He was a man so powerful that in a single session at his typewriter, he could sway opinions for or against a particular rifle caliber. Because of Jack’s writings, some calibers, such as the .270 and .243, prospered over the years, and others died a quick death.

In 31 years, Jack had written almost 400 columns, in addition to 200 feature stories for Outdoor Life and more than a dozen hunting and shooting books.

Jack had hunted throughout most of the world and was considered the last word in sheep hunting and rifles. If you had a question about a big-game animal or a gun, you called or wrote to Jack O’Connor. He tried to answer every letter. By his count, he had responded to more than 200,000 pieces of mail.

A few months before the hunt, Jack had called and asked if we could hunt whitetails and pronghorns in Montana. I was overwhelmed at the idea.

I’m a hunter’s booking agent. I’d arranged many hunts for Jack in Africa, Canada, Alaska and in the continental United States, and had accompanied him on some of those hunts. But this was the first time I’d have him all to myself because I’d be his guide. I was beside myself with the enormity of it all.

SO THERE WE WERE, sitting on a log in Montana. At least 20 other whitetails were with the big buck, including two other very large bucks that looked like twins but which were easily outclassed by the giant. But Jack was positioned so that he couldn’t see the deer.

I knew that the deer wouldn’t hang around for very long. In fact, I wondered why they were there at all. The wind was blowing hard, carrying our scent directly to the whitetails. Jack and I were sitting on a log in a fairly open spot, and the deer were milling about in confusion just 50 feet away.

I didn’t dare move or talk for fear of spooking the animals. Somehow, I had to call Jack’s attention to them. He was sitting on the middle of the log. I was straddling the log so that I could look both ways. Jack was faced one way—the wrong way.

My rifle lay on my lap, along with a five-foot walking stick. Carefully picking up the stick, I eased it around and cautiously poked it into Jack’s back, hoping he’d realize that I was trying to signal him.

Because the wind was blowing so hard, Jack jabbed back at the stick, thinking that it was the pesky branch of a willow being shaken by the wind.

Either Jack would shoot the buck or no one would.

The herd of deer eyed us suspiciously. I became totally unnerved. I didn’t know what to do. Under other circumstances, I would have shot the buck myself, and that made me even more distressed.

Our hunt was in eastern Montana, the second part of a double-header. Prior to the whitetail hunt, we’d tried for pronghorn antelope in another area.

As it had turned out, the pronghorn hunt had been frustrating and disappointing, though we’d seen some enormous bucks. The only buck taken had been shot by Jack’s pal Henry Kaufman, who had accompanied us on both hunts. Also along was my friend Tom Radoumis, who Jack jokingly nicknamed Zeus because of Tom’s Greek ancestry.

I had done some scouting the day before Jack and Henry had arrived, and I had located a very big pronghorn that I judged to have horns between 17 and 18 inches. Another buck, with 16-inch horns, accompanied the larger antelope. Both were phenomenal animals.

My rancher friend had rigged a horse-drawn buckboard from which to hunt. But Jack wasn’t feeling well, so we drove the prairie roads in my Suburban.

Both big antelope were where I’d seen them the day before. A third buck, with 15-inch horns, was lying in a draw just below the other two. I had located the trio from a small knoll with my spotting scope, but when I returned to my vehicle with the good news, Jack said that he wasn’t up to the walk.

At that point, I realized that Jack O’Connor was failing. My hero seemed old and frail, and I was sad as well as frustrated.

The only chance we had to get close was to drive up a creek bottom on an old homestead road, and then try a short stalk, from below. A high ridge separated the road from the bucks, and I figured that we could get reasonably near to the animals.

I was in a hurry, probably driving too fast because I was thinking intently about the huge pronghorns. Suddenly, I looked out the window to my left, and there were the three bucks racing along beside the truck. Before I could react, the bucks veered sharply and dashed onto the road in front of us.

It was just a matter of luck that I didn’t run them over. My quick stop jarred all of us, and that was the end of the three pronghorns.

LATER IN THE DAY, we saw another good buck, but it was not as big as the large pronghorn we’d seen that morning. The animal was standing close to the road.

“Let’s try a trick,” Jack said. “Drive past the buck until we’re out of sight; then, you and Henry get out. Tom and I will park the vehicle where it’s visible. That will hold the antelope’s attention. Then, you and Henry circle around on foot and shoot.

“I’ve decoyed lots of sheep that way,” Jack continued. “A long time ago, I realized that animals can’t count people.”

Jack’s strategy worked, though at one point in the stalk, I was sure we had blown it. We had crawled past a pond full of geese and had alarmed the birds. They had flushed noisily, and I had expected the buck to take off, but his attention had remained riveted on the vehicle. Henry then made a fine shot, and we had our first pronghorn,

For the next two days, we did a lot of driving, and Tom and I did a lot of walking. Jack was feeling progressively worse, and he complained of being in a lot of pain. I was worried about what would happen if we found a trophy buck and had to make a long stalk.

Despite our efforts, we hadn’t located another worthwhile pronghorn close enough for a shot, and just as we were about to give up, I saw a golden eagle land beside a nest on a little rocky knob. The nest seemed to be unusually large, so I climbed the knob to have a look. I knew that the young eagles were fledged and long gone, but I was curious about the bones and remains of the eagle’s prey that would litter the immediate vicinity of the nest.

When I reached the knob, I looked down the other side and was startled to see the monster pronghorn bedded down just 100 yards away. The buck was very distinctive. Not only did he have enormous horns, but he also had very dark cheek patches that almost looked like eyes. I’d never seen an antelope with those markings before. There was no question. It was the same one I’d almost run over with the truck.

I slowly backed away from the knob and ran back to the truck to tell Jack about the antelope. When I reported our great luck, he sat quietly and didn’t say anything for a moment. Then, with regret in every word, he spoke.

“I’ve hunted all my life and never shot a 17-inch antelope,” he said. “I’d love to take him, but I don’t think that I should climb that hill.”

I was shocked and disappointed. “My God,” I thought to myself, “Jack isn’t going to try for the giant pronghorn!”

Until this hunt, I had been sure that Jack O’Connor could climb any hill, make any shot, do the impossible. Now, the realization that the dean of American hunters was old hit me hard. It was a helpless feeling.

I didn’t press the issue of trying for the antelope. The full realization of Jack’s physical condition stopped me. He had been much more aware of his difficulties than I.

“Why don’t you go up there and shoot that buck?” Jack said to me. “You’ve killed two 17-inch antelope. It would be nice to know that a pal of mine is the only man I know of who has taken three.”

Shooting a buck meant for Jack O’Connor while Jack sat in the truck was not something I could do. This was his hunt. Either he would shoot the buck or no one would. So we simply returned to the ranch.

THE SECOND RANCH, where we hunted whitetails, was in a lovely setting, with old cabins on a bluff above a river bottom surrounded by dense brush, cottonwood trees and lush croplands. Jack was awed at the thought that this area was once home to great herds of bison, elk and large numbers of grizzlies.

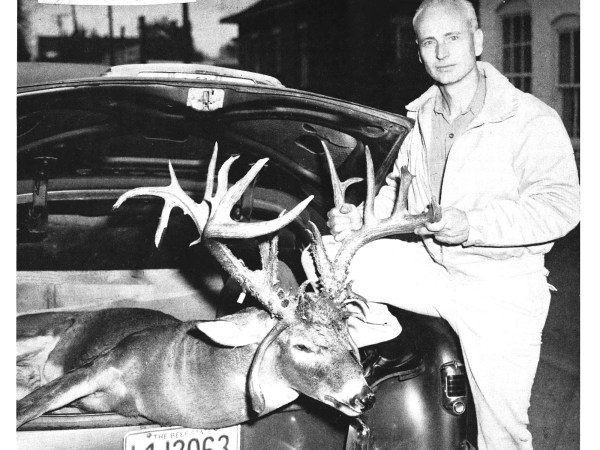

I did some scouting the evening before the hunt and saw at least 200 whitetails feeding in the alfalfa and slipping through the dense underbrush. I had seen some huge whitetails on that ranch on previous hunts, and I fully expected Jack to take the biggest buck of his life in the morning.

Guiding America’s top gun writer to a giant whitetail would be a highlight in my life. I can remember thinking about where Jack was likely to kill the buck, the kind of shot he would make and how I’d get the buck out. I even envisioned the way the head would be mounted for Jack.

I felt foolish telling Jack O’Connor to get ready. He was one of the most knowledgeable hunters I’d ever met, and he was indeed ready, but this was not a good day for Jack. It was like a bad dream.

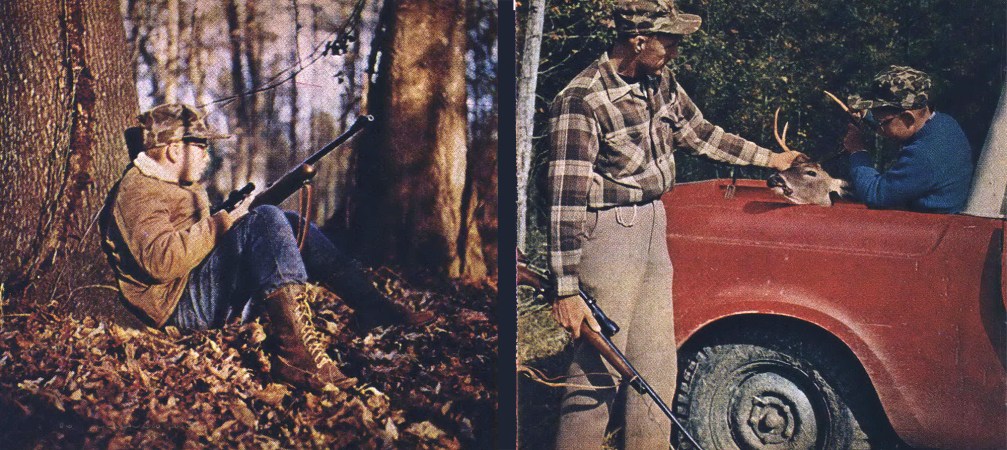

We positioned ourselves in a strategic stand the next morning, waiting for drivers on horseback to push deer around in the brush. It didn’t take long for whitetails to show up. Dozens of deer moved by us, including a number of bucks, but none were exceptional. As we watched, it became obvious that Jack was having problems with his vision. He saw few of the deer; and those he saw were fairly close and easily visible. I’d never seen more whitetails on a drive in my life. They came by constantly, along with foxes, coyotes, raccoons and pheasants. It was a great show. Jack seemed to be enjoying it immensely. We talked of many things.

At one point, he reminisced about driving tigers in India and how often the beaters were mauled by tigers. He noted that if we had been hunting tigers, the situation would have been vastly different for the men on horseback. It was common, Jack said, for tigers to attack elephants and their riders beating the brush.

The subject turned to Jack’s hunting preferences.

“What do you like to hunt most?” I asked.

“Sometimes, I think I like to hunt tigers, sometimes sheep, and right now, whitetail deer. I guess that I like to hunt everything, as long as the animal has a fair chance.”

After several more drives, the day ended without Jack having fired a shot. But he’d had chances at several respectable bucks. Jack had not wanted to shoot an average buck because he’d taken many such bucks. He had wanted something more.

“I’d like to take one really good whitetail buck,” Jack said as we walked to the vehicle. “But if a hunter wants to shoot big bucks, he must learn not to shoot the small ones. This may mean you go home empty-handed a few times, but that is the difference between hunting and trophy hunting.”

“It doesn’t hurt to be lucky, too.” I remarked.

“And maybe 30 years younger,” Jack said, as we headed for my truck.

Before we reached the truck, I pointed to a stand high in a tree and told Jack that a hunter had fallen out of the stand and had been killed the previous year.

“I cannot think of a better way to go,” Jack said with a slight smile. “I don’t want a long, lingering death; I want to die quickly. I’d like to die while on a hunting trip and have my ashes spread over the sheep country in the Yukon.”

Jack’s words seemed to reinforce a strange feeling I had that this would be his last hunt. Somehow, I believe that he felt it as well.

THE NEXT DAY, while we were driving to a stand, a very large buck ran across the dirt road in front of us. It stopped and looked back. The deer was so close that I could see his bulging eyes.

Instead of running off immediately, the deer stared at us. Jack had difficulty seeing it, and he made a hasty effort to get out of the vehicle. But Jack’s bulky winter clothes and boots hung up on the truck door handle and the seat. He cursed his 75 years, the manufacturers of bulky clothes, Stetson hats and long-barreled rifles.

By the time he finally got out, the buck had seen enough and was running through the brush. Although a shot would have been possible, Jack got back in the car and sat without saying a word.

It was obvious that Jack was terribly frustrated and in a great deal of pain from his arthritis. I felt badly for him. In earlier years, no running buck was a match for Jack O’Connor’s incredible shooting.

Finally, Jack started to laugh at the humor of the situation.

“I don’t think that deer deserved to be shot,” he said, grinning. “Anyone who is so old and decrepit that he can’t get out of a vehicle while a deer waits to be killed, shouldn’t have a shot anyway.”

The old hunter had a wry sense of humor, and didn’t mind poking fun at himself. But he was frustrated, and we all felt his helplessness.

Later that morning, several whitetails appeared before our stand. Some were very fine bucks. Tom and the horseback riders were doing their best to keep deer in front of us. Occasionally, Jack would raise his rifle, look through the scope, and lower it again. When one particularly good buck went by and Jack didn’t shoot, I asked him why he was hesitating.

“I can’t see the antlers very well,” he said.

Just then, a big buck appeared and stood against a red riverbank. The buck was a reddish color, and it was standing in the open. I pointed the buck out to Jack, but he couldn’t see it. I realized that the only way Jack would be able to see a buck well enough to shoot was if it was in front of a sharply contrasting background. And it would have to be very close.

Despite bad luck throughout both hunts, Jack kept his good humor and told us more stories of his hunts. I think he perceived my personal frustration that he hadn’t scored. He was trying to make me feel better. But Tom and I hadn’t given up. We were determined to give Jack the best hunt he ever had, with or without luck.

Our next plan was to go to a spot where I’d previously seen a truly big buck. Whitetails normally hang out in the same area, and we hoped to see this particular buck again.

Jack and I walked to the log I’d selected to watch from, and now understanding his visual problem, I positioned him where he could look down a narrow corridor that had a light background of grass. A heavy frost as bright as snow provided a contrasting backdrop.

Tom and the other drivers were good. Before long, a number of deer ran in front of Jack and me. A dozen does passed through the corridor Jack was watching. Following was a nice buck that bounded through so fast that Jack couldn’t react in time.

More deer, including several good bucks, ran through, and Jack looked at me with a pained expression. “I’m rattled,” he said. “I must be coming down with buck fever.”

I couldn’t believe the deer that were running by. I’d never seen more whitetails in my life. I don’t think that Jack was really suffering from buck fever. He was having difficulty seeing antlers, and his old painful limbs simply prevented him from reacting quickly with his rifle.

The wind had begun to blow furiously just before the 20-plus deer, including the giant buck and his twin accomplices mentioned at the beginning, showed up. I firmly believed that the gods were setting the stage for Jack O’Connor’s final act.

I’d never been in quite such a predicament before. I was poking Jack in the back. He was jabbing at the stick. And a record-class whitetail was watching our performance.

Instantly, the first two bucks were alarmed by our movements and ran. They made so much noise that Jack quickly turned and saw them disappear into the brush.

“Damn!,” he said. “How can my luck be so bad?”

As soon as he spoke, he spotted the big buck, but it was too late. The animal quickly melted back into the willows.

Suddenly, I saw the twin bucks heading back toward the corridor that Jack had been watching. One of them stopped near a dead snag and stared at us.

“Shoot, shoot,” I whispered. But Jack didn’t shoot because most of the deer’s body was hidden.

“Get ready,” I warned. “Here comes the second buck.”

I felt foolish telling Jack O’Connor to get ready. He was one of the most knowledgeable hunters I’d ever met, and he was indeed ready, but this was not a good day for Jack. It was like a bad dream. To me, the champion of hunters was now in the ring, under the spotlight, with the crowd cheering. But suddenly, that dream was shattered as the young champion I remembered became the old hunter.

At that moment, I felt a warm but sad kinship with Jack. It was like discovering that your dad had grown old before your eyes and being stunned by his inability to do the things that both of you had once done so easily. It was like pleading, “Come on, Dad, let’s do it,” and your dad replying, “I just can’t do that anymore, son.”

THE TWO BUCKS moved away, but they were positioned where I could make a quick dash and possibly force them through the opening where Jack could see them.

I ran, and everything seemed to be going well, but the bucks suddenly vanished, as happens so often with whitetails. They were gone. No amount of wishing could bring them back.

At that moment, the wind stopped and the woods grew silent. I was never so disappointed in my life. I turned around to pick up my rifle, and was astonished to see the giant buck once again. The great whitetail was in the open, standing broadside, looking directly at me.

Picking up my rifle, I slowly turned my head and saw Jack looking the opposite way. He was still watching for the twin bucks that had made off in another direction.

I whispered loudly to signal Jack, but my voice spooked the buck. He whirled and crashed into the willows, bounding off in a way I knew was for keeps.

I was heartsick. Why did so many bucks present themselves, and why were we so unlucky?

Then, the impossible happened. The huge buck stopped running and trotted right back to the very place he had just left. It was too much. I raised my rifle, aimed at his heart, but could not pull the trigger. I was staring at what might have been the biggest buck in Montana, but I couldn’t shoot. I desperately longed to hear the roar of Jack’s .270. There was no reason in the world why that buck should have returned and presented himself for another shot. It was as if the good Lord was giving Jack O’Connor the finest show of his life.

I raised my rifle again, but could not bring myself to fire it. This was Jack’s hunt, not mine, even though he had insisted that I shoot if I had an opportunity.

Read Next: Jack O’Connor’s Final Word on How to Pick a Deer Rifle

The enormous buck spun and ran off, this time for good. I turned and was shocked to see Jack standing with his rifle to his shoulder, aiming at the buck. He was grinning from ear to ear, and I realized that he had seen the buck, but for some reason had refused to shoot.

“God, what a buck,” he said simply. “What a buck!”

As we left the woods, our hunt over, I couldn’t bring myself to ask Jack why he hadn’t shot. Perhaps he’d seen me drawing a bead on the buck and wanted me to take it.

Perhaps. Or maybe he hadn’t fired because he believed that once you take the biggest buck of your life, there’s nothing to look forward to.

Jack O’Connor passed away the next spring, in 1978. I have returned to the whitetail ranch several times since Jack’s death. I never saw the giant buck again, nor have I ever again seen the unbelievable number of bucks that we saw on his last hunt.

I’m convinced that someone up high was pulling for old Jack. Jack was one of the finest hunters and shooting writers who ever lived. It was fitting that he was shown such a superb parade of whitetail bucks the last time he carried a rifle in his beloved American West.

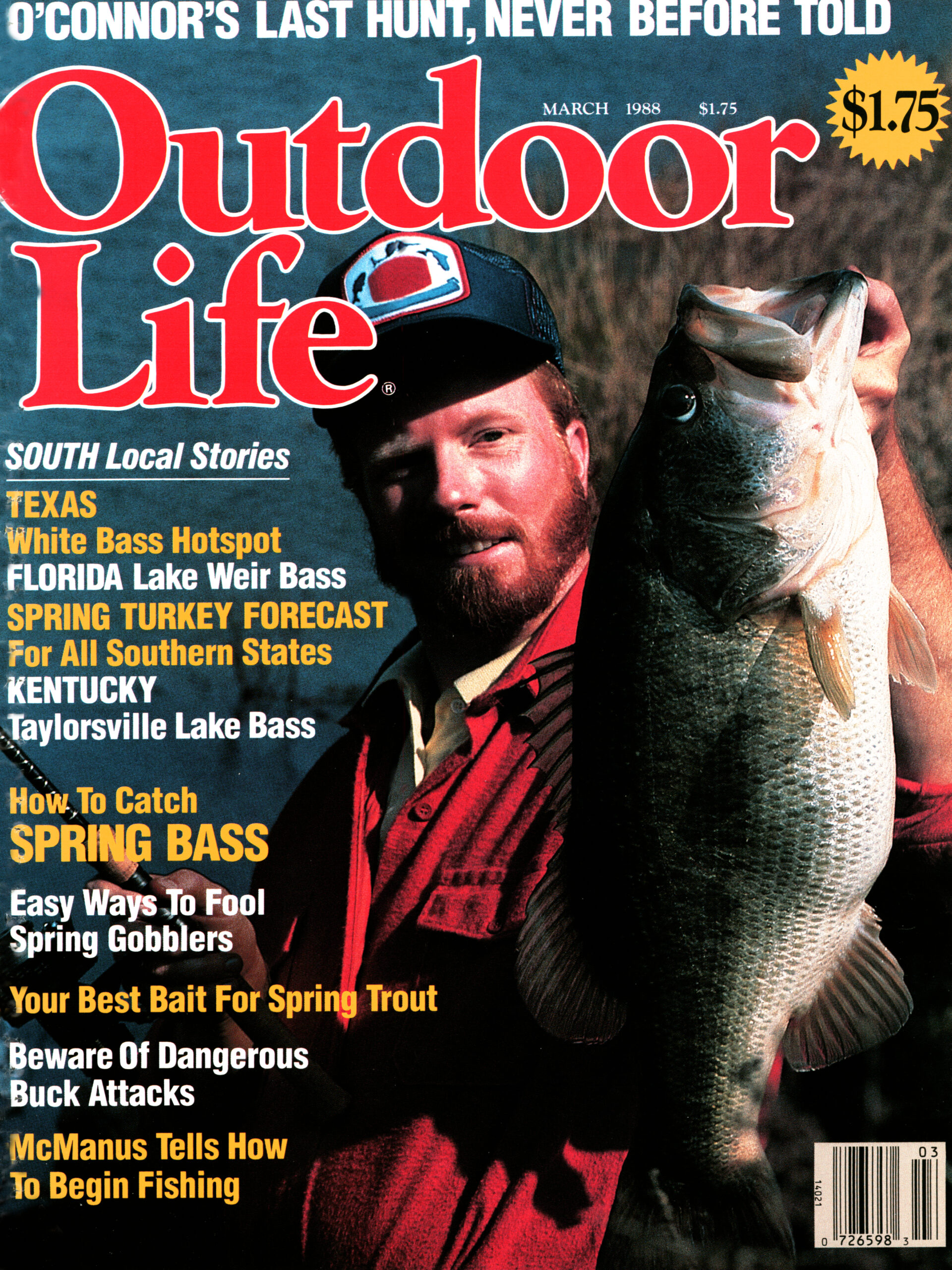

This story originally ran in the March 1988 issue of Outdoor Life.