Updated April 5, 2022: Although officials with Colorado Parks and Wildlife initially advised the public that a controversial elk hunt near Telluride had occurred legally last fall, recent charges revealed that the hunter’s actions leading up to and following the hunt were in violation of a local ordinance. The hunter was charged in February and pled guilty to carrying a firearm onto the Valley Floor.

When we think about elk hunting in the West, we tend to imagine bulls bugling in the backcountry, and trekking through mountainous terrain. We don’t dream about quartering an elk within sight of tourists who are hiking on the outskirts of a Colorado ski town. And for most hunters, the thought of being unable to recover multiple elk as they rot along a popular trail is straight-up horrifying.

But both of these nightmare scenarios played out this season as out-of-staters literally took their hunts right to the legal line. And although investigating officials found that the hunters in both cases did nothing illegal, these incidents stirred controversy among non-hunters and local hunters alike.

So as new technology helps us uncover the tiniest slivers of legal hunting land, and hunting pressure squeezes more of us into these areas, this ethical question is going to become more and more pressing: Just because you can legally hunt somewhere, does it mean you should?

Colorado: Hunting a Ski Town’s Resident Elk

The most recent incident occurred near Telluride, Colorado, on Nov. 6 when an out-of-state hunter shot an elk on a small piece of public land known locally as “the Wedge.” The Wedge is sandwiched between the resort area of Mountain Village and Telluride’s Valley Floor—an iconic, open public space that lies just outside of town.

Anyone who has visited or lived in the small, exclusive ski town has driven past the Valley Floor, since it lies on the south side of the only road in and out of the valley. The scenic 570-acre parcel is privately owned by the town of Telluride, and it features multi-use trails, access to the San Miguel River, and a large resident elk herd. It’s a postcard landscape that gives locals a space to hike, bike, and cross-country ski, and provides rubbernecking tourists with endless photo opportunities.

So, when a shot rang out on an otherwise quiet Saturday morning, and a bull elk ran downhill into the Valley Floor and died, people noticed.

“The hunter called our local office right away and asked for guidance on what he should do in regards to retrieving and packing out that animal,” says Colorado Parks and Wildlife public information officer John Livingston.

A CPW game warden arrived on the scene, Livingston explains, where he was joined by an officer from the Telluride Marshal’s Department. After a brief investigation, the officials determined that the elk was taken legally, and that the shot was fired safely. The hunter was then allowed to walk down into the Valley Floor—where a crowd of onlookers had already gathered—to retrieve and pack out the meat.

Livingston confirms that the hunter had a GPS app on his phone, which allowed him to geo-tag the exact location where he had shot the elk. These coordinates proved that both he and the bull were on Forest Service land—and within the state’s Game Management Unit 70—when the hunter fired his rifle.

Still, Livingston says that the hunter was walking a fine line by choosing to hunt there, and he told the Telluride Daily Planet as much after the incident occurred: “If the elk had been 10 yards further down the hill, maybe it would have been down on the Valley Floor and on that private land. The hunter was able to get this done by the skin of his teeth. There’s no doubt about that.”

Livingston does make it clear that hunters have taken game from the area before, and that even though the Wedge “is this little sliver of maybe 10 to 20 acres of public land, it’s all multiple-use trails in there. And hunting is part of that multiple-use designation for our Forest Service lands here in Colorado.”

He says that he knows of one hunter who successfully hunted the Wedge during this year’s archery season, but that “because of the nature of it, nobody in town was super aware of it. Mainly because they didn’t see a hunter in blaze orange down in the Valley Floor dressing an animal.”

So when non-hunters in Telluride were confronted with this sight, it didn’t sit well with them. When the local newspaper shared the story on its Facebook page, many of them were quick to weigh in. Some commenters brought up what they saw as legitimate safety concerns with discharging a firearm that close to a popular public open space. Others cranked up the anti-hunting rhetoric, calling the incident a “slaughter, whether it was officially legal or not.”

More than a few local hunters came to the out-of-state hunter’s defense, saying that “public land is public land” and that “the hunter took the animal legally – time to move on.” Some hunters also accused detractors of jumping on any opportunity to restrict access for one particular user group (i.e., hunters) while simultaneously promoting access for other users (i.e., hikers, mountain bikers, and cross-country skiers.) At least one commenter agreed that the out-of-state hunter did nothing illegal, but he did question the hunter’s ethics.

“I know some locals who have said that they know they could hunt there, but they choose not to because they don’t think it’s very sporting,” Livingston says. “That herd is so docile, and at that point it’s a shooting-fish-in-a-barrel kind of deal.”

Of course, all things are relative, and if we’re really talking about shooting fish in a barrel, we need look no further than the incident that occurred just outside of Jackson, Wyoming, just a few months earlier.

Wyoming: Shooting Elk You Can’t Recover

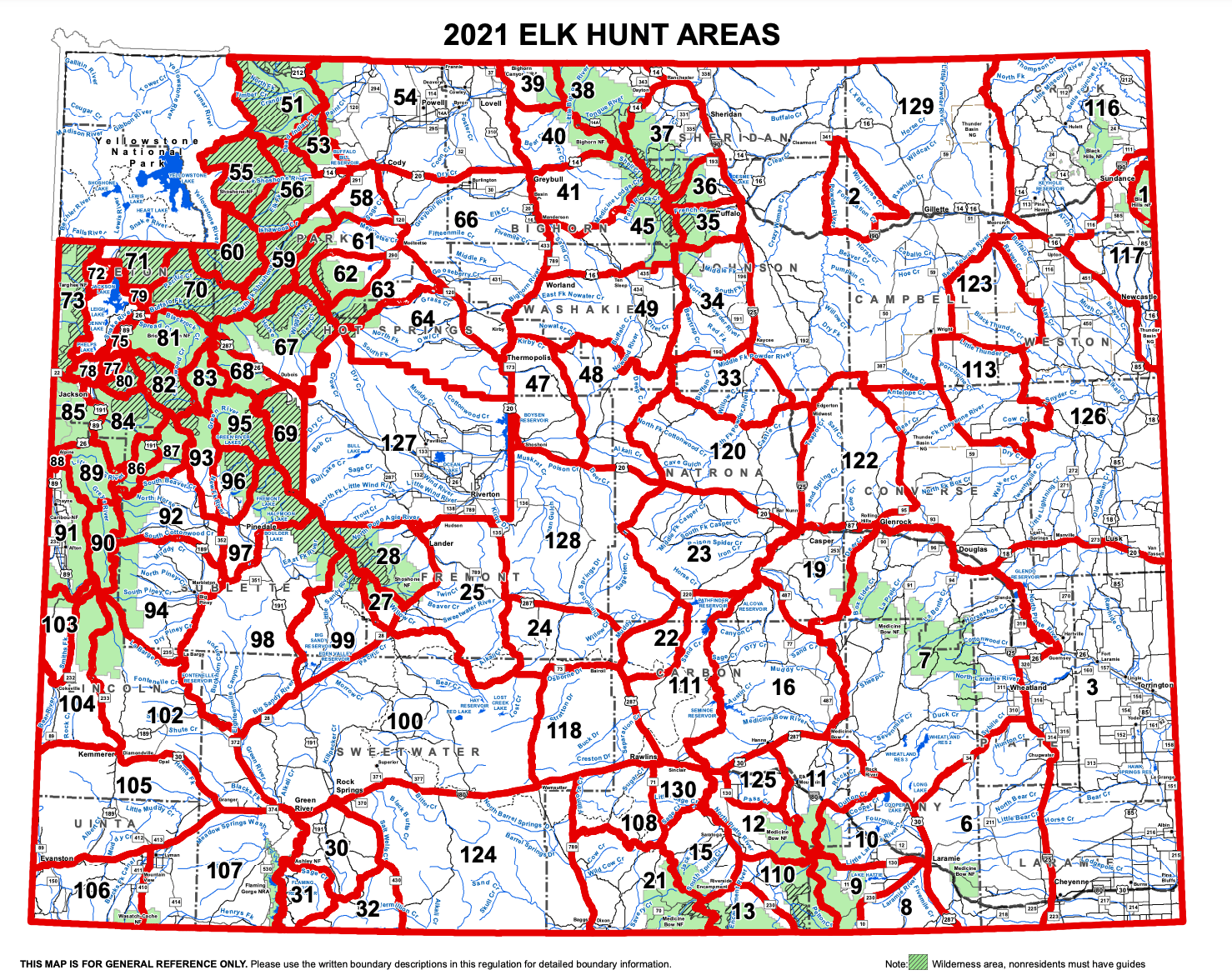

As Jackson Hole News & Guide reported, Sept. 26 was a beautiful Sunday morning and three hunters from Minnesota were on their first ever Wyoming elk hunt. The hunters had their hunting licenses along and several nonresident tags, and they were within the boundaries of the state’s elk management unit No. 78 when they started their hike from Emily’s Pond Levee on the east bank of the Snake River, about five miles from the Jackson Town Square.

The non-resident hunters, who were all over the age of 65, walked a mile or so up the river that morning. Around 9 a.m. they stumbled upon a group of elk standing on an island in the middle of the river. They fired off seven shots, dropping three cows and a calf, and in their excitement failed to recognize the situation they were getting themselves into. Now seeing that the river was too swift for them to cross on foot, they watched boatless and helpless as the four carcasses sat in the sun.

By early afternoon, many locals had already arrived at the well-known trailhead, and the hunters were shocked to see so many people jogging, walking dogs, and pushing strollers up the trail. The Wyoming Game and Fish Department began to receive calls about illegal activity in the area, and the three hunters were soon confronted by some locals, who were furious.

One Jackson Hole resident, a hunter himself, explained to the Minnesotans how hunting in that location and shooting those elk was actually a major disservice to the local hunting community.

“I told them they’d set back years of effort to create goodwill between the non-hunting community and hunters,” he told the local newspaper. “It’s an ethical question, and that’s not fair chase, cornering them on an island and mowing them down.”

A game warden eventually arrived on the scene that afternoon. He confirmed that the elk were taken legally, but that the hunters still had to retrieve the animals within 48 hours of when the shots were fired to be in accordance with state law.

The Minnesotans called some friends who were in the area and got their hands on a canoe, but they promptly flipped the boat when they tried to ferry across the river, and they were forced to leave at sunset. They rented a raft in town the next morning, and then floated to the island where they packed out the elk by 6 p.m. that evening, a little more than 30 hours after the whole debacle began.

Mark Gocke is a Jackson local and a public information specialist with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department. He explains that the hunters were apologetic and regretted their decision to take the elk.

“They said so themselves that, had they known there were that many people who used the area to recreate and walk dogs and such, they wouldn’t have gone there in the first place,“ Gocke says. “And that’s one of the things that I take away from this incident. Any hunting outing that you go on, there’s a lot of preparation and prior planning that’s involved. And these hunters probably could have done a better job of planning prior to coming out to Wyoming to hunt.”

Gocke, who has lived and worked in the Jackson area for 25 years, is familiar with the elk management unit that encompasses the Emily’s Pond area. He explains that the unit is made up of mostly private land with patches of BLM land, and that “it’s a place that we actually discourage people from hunting because there’re a lot of non-hunters there and homes that are fairly close.”

He says that local waterfowl hunters have, on occasion, floated down that stretch of river and hunted out of rafts, but that he’s never heard of anybody actually hunting big game there.

Read Next: How to Beat the Crowds in the Public-Land Whitetail Woods

The way Gocke sees it, the hunters’ lack of planning was their first major mistake, but ethical decision-making really came into play when they came upon the elk on the mid-river island. They killed the elk without a plan or the means to recover them.

“We have laws that govern hunting, and some that address ethics, but there’s always going to be some responsibility on the hunter to know when they should be taking shots, and where they should be hunting to do it safely and ethically,” he says. “It’s what you would do if you knew nobody was watching, and it’s a decision that every hunter has to face at some point in their hunting career.”

What Hunters Can Learn from These Legal Elk Hunts

In hindsight, each of these instances could have been worse for the hunting community. No one was injured, no laws were broken, and the elk were recovered safely in the end. There are, however, some lessons that hunters can take away from both of these problematic, albeit legal, elk hunts.

Both these hunts involved non-residents who found themselves hunting public (very public) places that the locals usually don’t hunt. And in both instances, the out-of-state hunters relied on modern mapping apps like on X Hunt to determine where they could legally hunt. While these apps have certainly changed the game for hunters exploring new territory, traditional boots-on-the-ground scouting is still important. An extra day of scouting ahead of their hunt might have alerted both parties to the complexities of trying to hunt in those locations, and they may have moved on to try and find elk elsewhere.

While hunters shouldn’t be overly concerned with how non-hunters view legal hunts on public land, it’s also in our best interest to do so as discreetly as we can. So, if after taking all of this into consideration, you want to or must hunt right near a popular public area, do it the right way.

Call the local game warden ahead of time and inform them of your hunting plan. Be discreet and hunt with a bow if you can. If you’re a rifle hunter, consider using a suppressor if your state allows it. Either way, take only perfect shots. And if you can, choose to hunt on weekdays or during other times when public lands are less crowded with other users. Have a plan for how you’re going to recover the animal and pack it out. If that plan includes the possibility of being blasted by the local news station, then it’s a bad one. Ultimately, it’s your right to hunt on public land that’s legally open to hunting. But those rights can and will be limited if the general public decides it doesn’t like hunting. We all must do our part to avoid that.

Lastly, know when to call it off and find another place to hunt. Because, at the end of the day, hunting in new territory is one of the most exciting aspects of the sport. Seizing the opportunity to chase elk in Western states like Colorado and Wyoming should be a dream—and not a nightmare—come true.