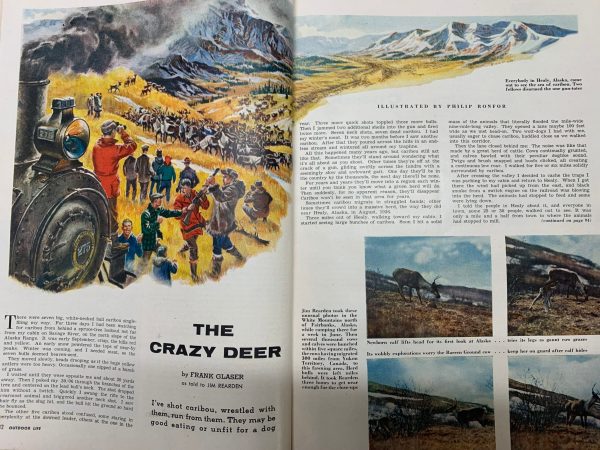

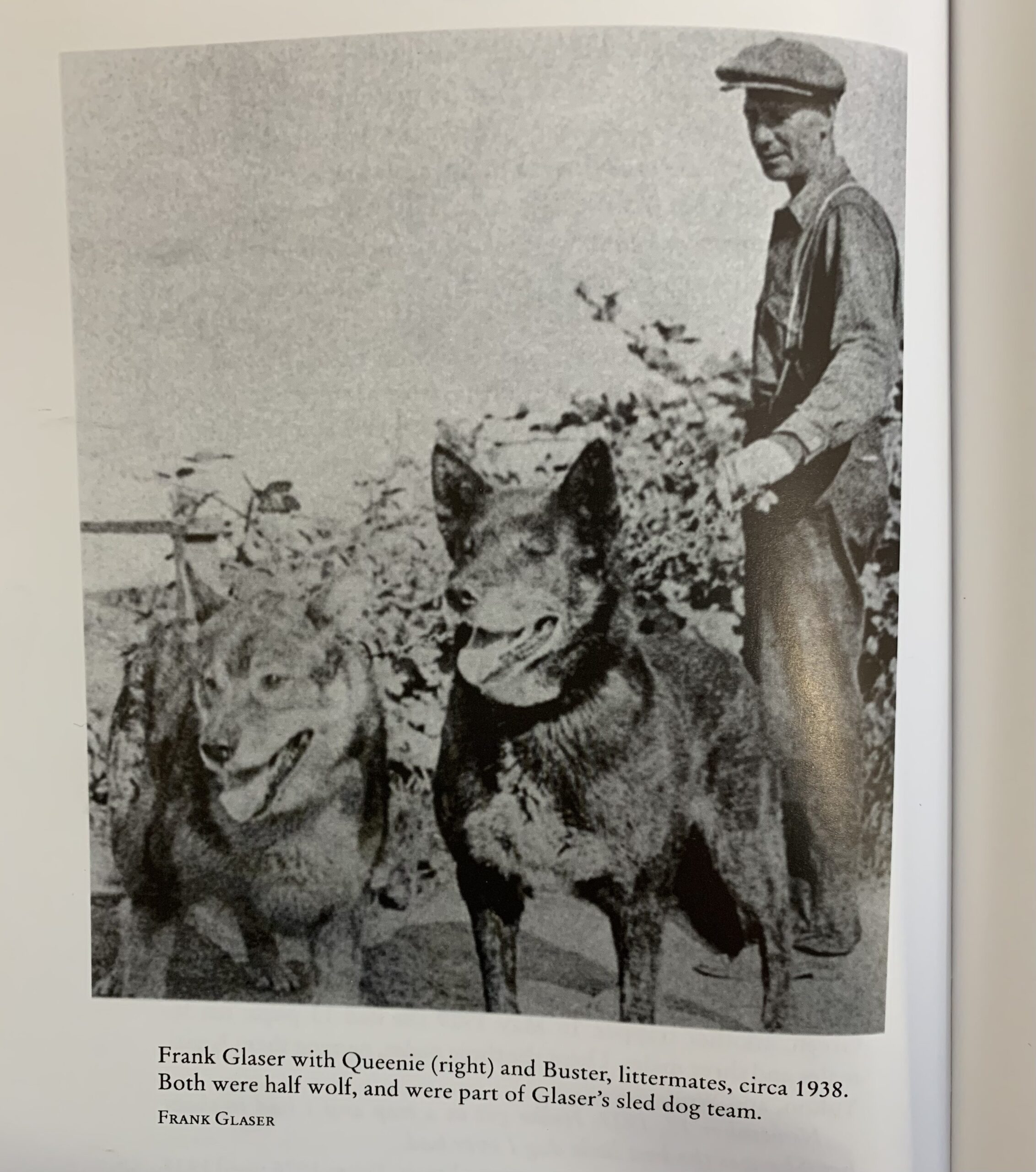

In over a hundred years, Outdoor Life has published thousands — tens of thousands — of stories by many notable storytellers. One of those writers is Frank Glaser, whose tales of Alaskan adventure were printed in the pages of Outdoor Life after they were put to paper by longtime contributor Jim Rearden. Rearden’s 1998 book, Alaska’s Wolf Man, re-tells many of Glaser’s tales, just as it tells the bigger story of one of the most incredible Alaskan icons.

Along with becoming a legendary Alaskan, Frank Glaser was a passionate conservationist. He spent time as a market hunter, trapper, and federal predator-control agent over a period of 40 years in Alaska. He was educated through the experience of spending years of his life alone in the wilderness. According to Rearden, Glaser possessed an encyclopedic knowledge of wolves and he was often as a source of information on wolf behavior for biologists at the time. He cared deeply about Alaska’s game animals and other wildlife, and although he might not have set out with adventure as his purpose, his lifestyle mandated it.

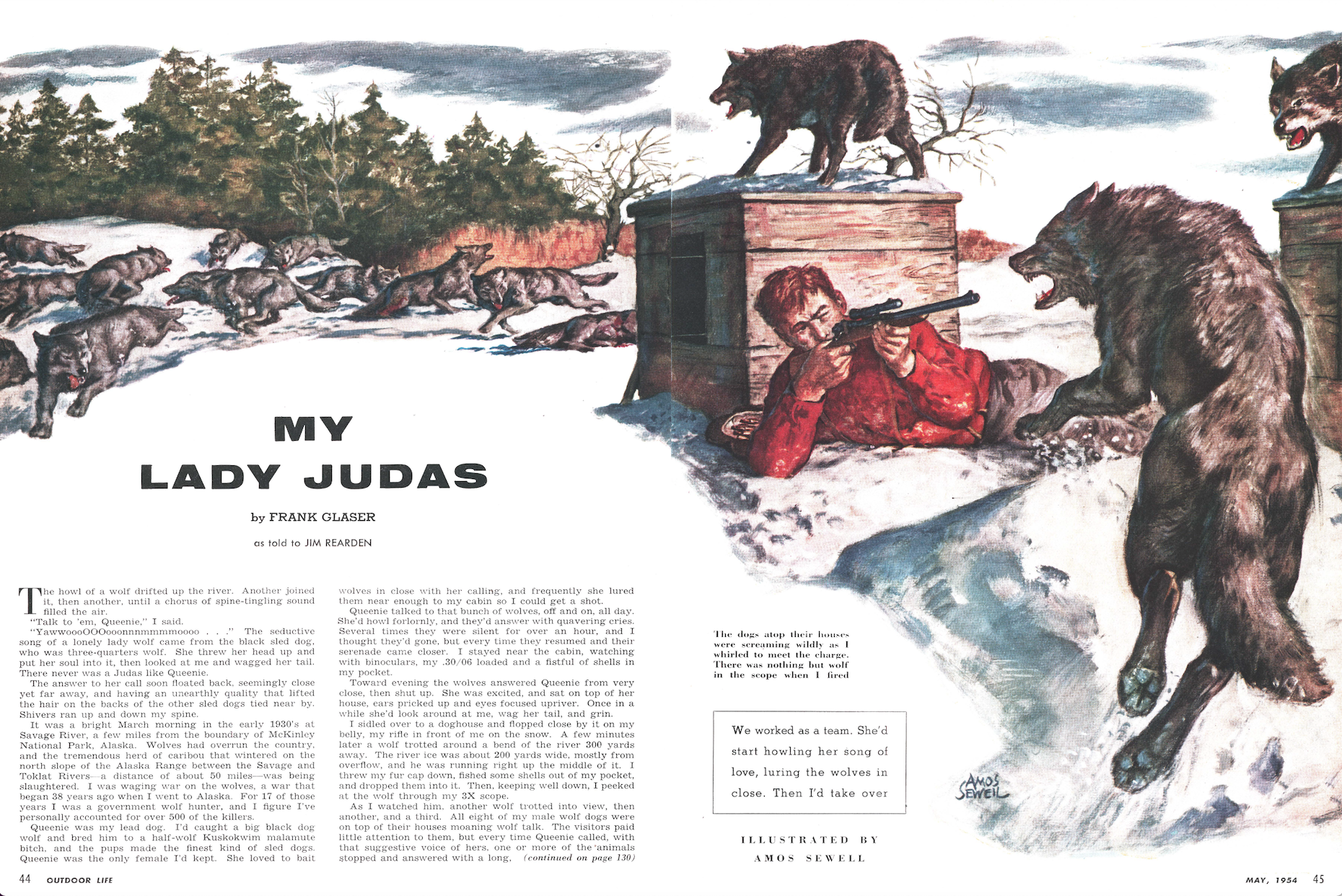

This story, originally published in Outdoor Life in May 1954 under the title “My Lady Judas,” tells the story of how one of Glaser’s wolf-dogs helped him hunt a pack of wolves. —Tyler Freel

My Lady Judas

THE HOWL of a wolf drifted up the river. Another joined it, then another, until a chorus of spine-tingling sound filled the air.

“Talk to ’em, Queenie,” I said.

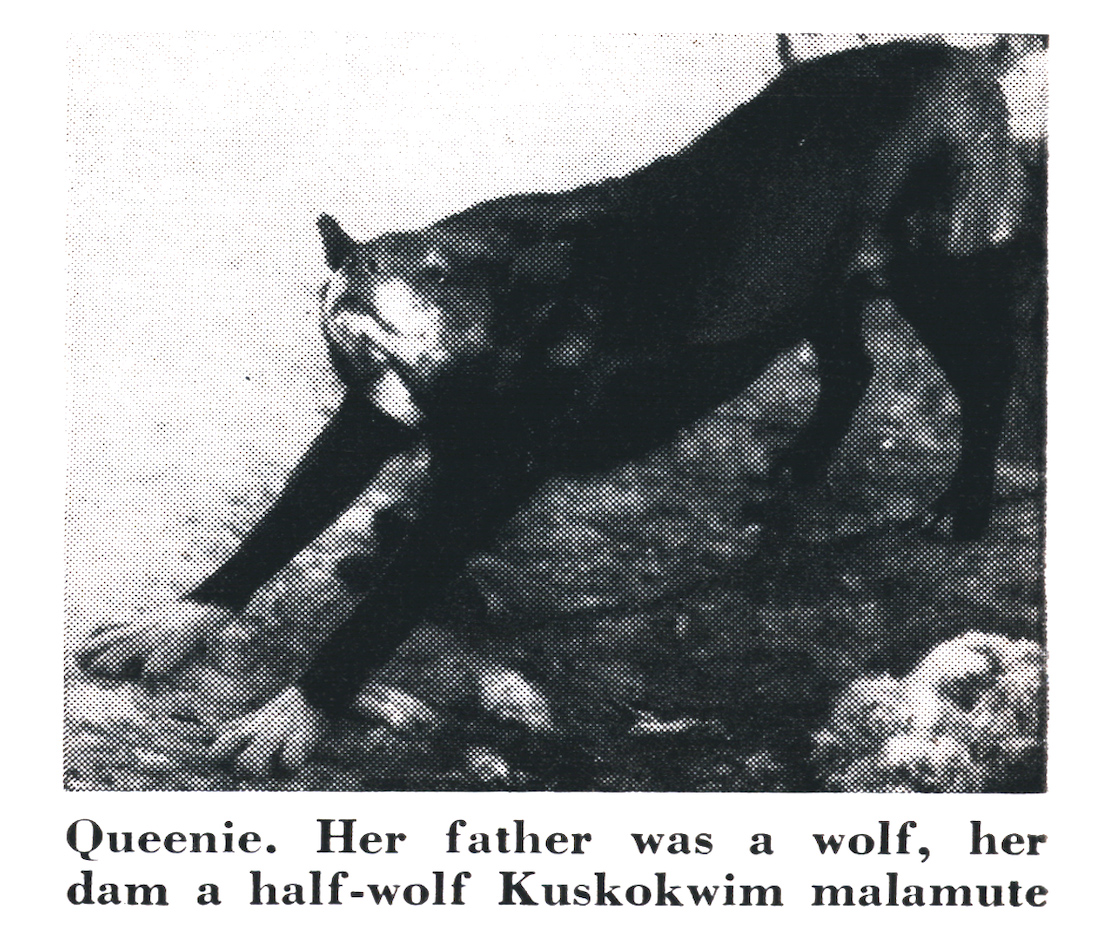

“YawwoooOOOooonnnmmmmoooo…” The seductive song of a lonely lady wolf came from the black sled dog, who was three-quarters wolf. She threw her head up and put her soul into it, then looked at me and wagged her tail. There never was a Judas like Queenie.

The answer to her call soon floated back, seemingly close yet far away, and having an unearthly quality that lifted the hair on the backs of the other sled dogs tied near by. Shivers ran up and down my spine.

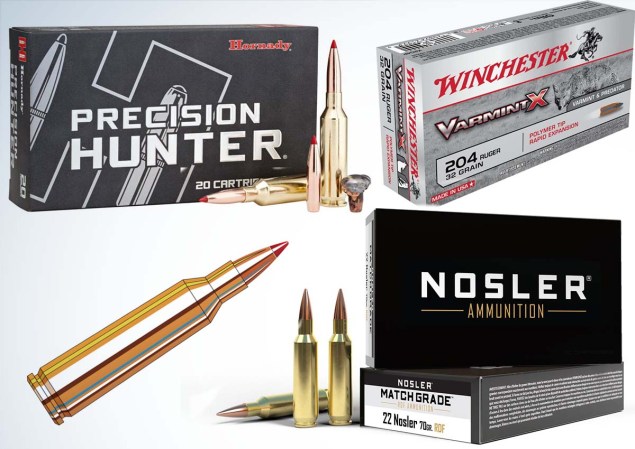

Read Next: The Best Hunting Rifles, Tested and Reviewed

It was a bright March morning in the early 1930’s at Savage River, a few miles from the boundary of McKinley National Park, Alaska. Wolves hand overrun the country and the tremendous herd of caribou that had wintered on the Savage and Toklat Rivers — a distance of about 50 miles — was being slaughtered. I was waging war on the wolves, a war that began 38 years ago when I went to Alaska. For 17 of those years I was a government wolf hunter, and I figure I’ve personally accounted for over 500 of the killers.

Queenie was my lead dog. I’d caught a big black dog wolf and bred him to a half-wolf Kuskokwim malamute bitch, and the pups made the finest kind of sled dogs. Queenie was the only female I’d kept. She loved to bait wolves in close with her calling, and frequently she lured them near enough to my cabin so I could get a shot.

Queenie talked to that bunch of wolves, off and on, all day. She’d howl forlornly, and they’d answer with quavering cries. Several times they were silent for over an hour, and I thought they’d gone, but every time they resumed and their serenade came closer. I stayed near the cabin, watching with binoculars, my .30/06 loaded and a fistful of shells in my pocket.

Toward evening the wolves answered Queenie from very close, then shut up. She was excited, and sat on top of her house, ears pricked up and eyes focused upriver. Once in a while she’d look around at me, wag her tail, and grin.

Read Next: When Wolves Attack: Five Close Calls from Wolf Country

I sidled over to a doghouse and flopped close by it on my belly, my rifle in front of me on the snow. A few minutes later a wolf trotted around a bend of the river 300 yards away. The river ice was about 200 yards wide, mostly from overflow, and he was running right up the middle of it. I threw my fur cap down, fished some shells out of my pocket, and dropped them into it. Then, keeping well down, I peeked at the wolf through my 3X scope.

As I watched him, another wolf trotted into view, then another, and a third. All eight of my male wolf dogs were on top of their houses moaning wolf talk. The visitors paid little attention to them, but every time Queenie called, with that suggestive voice of hers, one or more of the animals stopped and answered with a long, low, sweet howls that chilled my blood.

The moose finally stopped out in the open, and turned to fight the wolves. As they closed in she tried to whirl and face each wolf as it attacked, but she was too slow.

Wolves kept trotting into sight, traveling single file, until I thought there’d be no end to them. They’d run a short way, stop, look back suspiciously, then catfoot closer. The lead wolf was within 50 yards of me before the last one in the pack came around the bend. Before I fired I counted 27 wolves strung out across that snow-covered bar and river ice.

Slowly and carefully I laid the post of the scope just below the withers of the last wolf, and squeezed off. The animal, a small black, dropped on the ice. By the time I’d pulled the bolt and rammed in another shell at least 15 of the wolves had bunched up and were running away from the dead wolf towards me. Two quick shots into the massed animals killed two and left another floundering on the ice, dragging its back legs toward the near-by willows. The remaining 23 scattered like dry leaves in a whirlwind, running frantically in all directions, throwing snow, and scratching the hard ice as they sprinted away.

Some headed directly for the doghouses, running low, their tails straight out behind them, mouths open, ears flat against their heads. Apparently they thought my dogs were wolves, and figured it would be safe to be near them. The dogs loved it, and all were screaming at the top of their voices.

I was starting to center the scope on a big black wolf 70 or 80 yards away when out of the corner of my eye I saw ears, close. I yanked the rifle around just as a wolf came over a cutbank not 10 feet away. There was nothing but wolf in the scope when I pulled the trigger; I just about blew him off the end of the gun barrel.

Then I spotted a big gray brute streaking for the willows 150 yards downriver, centered on him, fired, and saw him plow his nose into the crusted snow and flop over. The animals were getting pretty well away from me by that time and I missed several shots, but I managed to connect once more. I’d burned up most of my shells, and the barrel on that old rifle of mine was sizzling.

I counted six dead wolves, then remembered the one that had dragged itself into the brush. When I got there I found it had crawled 20 feet and died with a bunch of branches in its mouth. I’d killed seven of the devils.

That was in March, during the breeding season, a time when it wasn’t unusual to see big wolf packs at Savage River. The largest I saw there during that time of year numbered 40, but the biggest I’ve ever seen had 52. I had lots of time to count, so know the number is correct. The funny thing about it is I saw them in October, which is wrong; wolves don’t normally gang up like that except at breeding time.

I’d been setting wolf traps in the White Mountain country and had just stepped away from one when I glanced at a ridge about a mile away and saw them, strung out single file. I thought they were caribou at first. They’d spotted me the minute I walked out of the brush, and by the time I centered them in my binoculars they were looking at me and howling.

Another strange thing about those 52 wolves was they were all blacks except two, and those were grays. The lead wolf was the biggest specimen I’ve ever seen — twice as big as the others — and I’d have given anything for a shot at him.

I howled at them, and they howled right back, making the canyon ring with their eerie wails. They were following a main ridge that had spurs dropping down into the canyon between us. Every time the big fellow came to a spur he’d walk out and look down, and all the others would stop. It seemed to me they were afraid of him, for during the whole time I watched not one came within good growling distance of him.

A week later I was snowshoeing along Fossil Creek on my way home. During the day I’d broken trail 10 miles to an old cache where I’d picked up a caribou-skin sleeping bag and some traps, and I started back at night. I’d slogged about a mile when a big gang of wolves commenced howling in the creek ahead of me. Then others howled behind me. I was carrying a .220 Swift, and began looking around for something to shoot.

I have an unearthly impression of that night. The air was still, and the only sounds I heard were the creaking and scuffing of my snowshoes and the wailing of the wolves. Snow sparkled in the bright moonlight, and occasionally the northern lights flung spectacular greenish flames across the sky. Several times I thought I saw a wolf and got ready to fire, then realized the shape was only a shadow.

As I moved among the spruces the wolves seemed to come closer. Once I whirled around, rifle ready, feeling as if half a dozen were about to leap on my back. Nothing. Later the howls came from four or five directions, and I felt certain I’d stumbled into that band of 52 again. They followed me right to the cabin, but I never saw a single one. The howling stopped when I lit a lamp.

Next morning I went back up Fossil Creek to where they’d started to follow me. I found they’d killed seven moose, all in that one place. As near as I could figure it, from the tracks and beds scattered around, it had been the 52 all right. Two of the slaughtered moose were young bulls, and the rest were cows, calves, and yearlings. The wolves spent two or three days there, and had left only the moose skulls, bits of hide and some cracked bones.

I wondered why so many wolves should have been running together in October. I think I know now. Wolves that follow migrating caribou generally hang around the rear of a herd. I have an idea a big caribou kill had been made, and the plentiful meat supply held the wolves together. Other wolves came into the area and stopped to feed on the dead animals.

Then it snowed, and the caribou herd moved faster. By the time the wolves had cleaned up all the carcasses and started to look for more animals to kill, the caribou were well away. The White Mountain country is poor for game except when caribou are there, and my feeling is those 52 wolves had banded together for hunting purposes. It’s only a theory, I know, but it’s based on known facts. Got any better ideas?

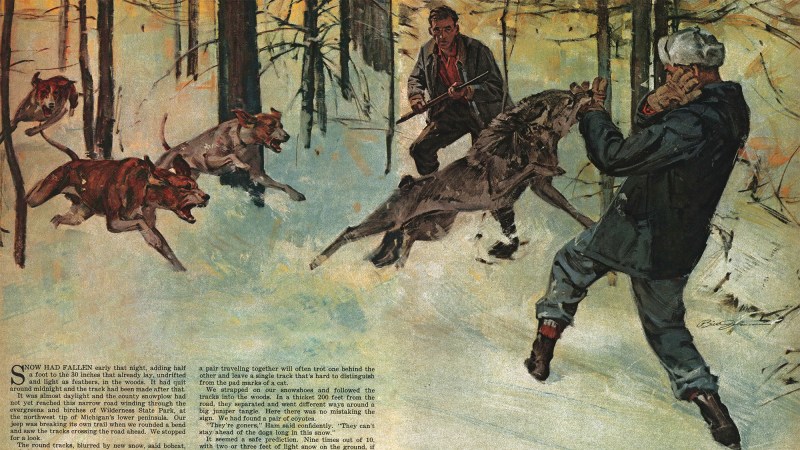

When a pack of wolves start in on a moose, the critter doesn’t stand much chance — unless he’s a big bull with antlers. One April I was watching coyotes running sheep in the hills when a cow moose showed up on the skyline. She was moving as fast as she could go, and kept looking back. Soon five wolves appeared on her trail.

Hoping I could save her, I grabbed my rifle and binoculars and hurried up the mountain behind my cabin to a lookout point. As I started up the ridge the wolves ran the moose into a patch of spruces. When she burst out of it a few minutes later I saw she was heavy with calf and staggering from exhaustion. I was much too far away to help her, and all I could do was watch.

Read Next: Do Wolves Attack Humans?

The moose finally stopped out in the open, and turned to fight the wolves. As they closed in she tried to whirl and face each wolf as it attacked, but she was too slow. The wolves jumped in and slashed, then leaped back. She stood on her hind legs and struck with her front hoofs, and several times she ran four or five steps while erect and tried to smash down one of the wolves. Her head swung back and forth, and her ears were back, but she couldn’t counter all the attacks. Whenever she lurched forward on her hind legs, one or two wolves tackled her from the rear. Finally they just swarmed over her and pulled her off her feet.

By the time I got there the pack had gulped down eight or 10 pounds of steaming flesh from the hindquarters. The moose was badly slashed, and big flaps of hide dangled from her. Some of the cuts on her shoulders looked as she’d been ripped with a sharp knife. The wolves had heard me coming, and had vanished.

The average Alaska wolf weighs from 80 to around 100 pounds, but sometimes a really big one turns up. The leader of those 52 was the biggest I’ve ever seen, dead or alive. He was bigger than the 212-pounder I saw actually put on a scale by the two Purdy brothers at Chicken, in the Fortymile country. They’d trapped it, and it was the biggest dead wolf that I have ever seen.

One of the biggest I’ve killed and weighed was one Queenie called for me. It was January, and bitter cold. For six weeks the thermometer didn’t get higher than 40 below, and often it seemed stuck at 60 or 65 below. One morning a wolf woke me with his howling. When it’s that cold sound carries unusually far, and that howler sounded as if he were right under my window. Actually when I spotted him with my glasses he was about half a mile away, on a hill. I’d see steam go up from his breath, then a second or two later I’d hear his cry. My wolf-dogs answered, Queenie especially.

The rest of the dogs gave up after a bit, but not Queenie. She sat atop her house and coaxed that poor wolf all day. There was no use my going after him, because the country was all open between him and the cabin and he’d have seen me the minute I started out. I watched him trot back and forth on the ridge, disappear, and show up on a near-by point where he could look down. Then he’d howl.

Outdoor Life

Another wolf to the south answered him for a while, and he kept glancing in that direction, but he’d look back to my dogs when Queenie spoke. Whenever she was quiet for too long, I’d tap on the window and give her the high sign. Then she’d cut loose with a heart-rending sob, look around at me, grin, and wag her tail.

Toward mid-afternoon Queenie was really putting out, howling low and intimate-like, and I could tell the wolf was coming closer. I slipped out of the cabin with my rifle, but it was too dark for me to see anything. I brought up the rifle, looked through the scope, and swung it back and forth. In a minute or so I saw what I thought was the same wolf silhouetted against the icy slope, about 200 yards away. I lowered the rifle until the scope post disappeared from sight on the wolf, let drive, and saw him collapse. I leaned the gun on the cabin and walked over to him.

I looked at him to be sure he was dead, then started to hoist him to my shoulders. I picked up his hind legs, slid them across my neck, and yanked hard enough to pull his flanks even with my shoulders. Then I bent over, strained, and glanced back to see how he was coming. About a third of his length was still flat on the ice!

All the dogs were yelling blue murder, so I let him flop back and went for a couple dogs and a sled. It was so cold that by the time I got him into cabin — not over half an hour after I’d shot him — his feet and tongue were frozen solid. He tipped the pointer on my beam scale to 154 pounds. His skin, cased, went 8 ½ feet long, and 16 inches wide at the center. A big wolf.

After skinning him I found five or six pounds of sheep meat and wads of sheep hair in his stomach. Next day, up on the hill, I found where he’d killed a three-year-old ram. He’d eaten some, and had tried to call more wolves to the feast. That was his mistake; he hadn’t figured on Queenie.

One November morning I was looking for fox sign on a big graveled ridge back of my cabin. Foxes were worth something in those days, and I made my living trapping them. There was no snow on the ground, an unusual condition for that time of year, and it was fairly warm — around zero. I happened to look to the north, and three miles off I saw something black on the side of the ridge about the top of the willow line. I focused my glasses on it and made out 20 wolves gathered around a kill. They started a fight while I was watching, flared away, milled around, and then went back eating. All but two were blacks.

There were some benches and drops between me and the wolves, so I lined myself up with a distant mountain and lit out in that direction. I lost sight of the pack, and didn’t see it again until I poked my head over the edge of the bench above them. Was I surprised! It had taken me about two hours to get there, and as I neared the edge of the bench I got down and started to crawl the last few feet so I could peek over.

I figured the wolves would be 300 or 400 yards away, but I stopped to check my rifle. Then I carefully worked to the edge, took off my fur cap, slowly raised my head — and looked a gray wolf right in the face. She had one foot raised at first, and stood there frozen just like a pointer dog. Out of the corner of my eye I saw the others strung out across the hillside, 20 or 30 feet apart. They’d eaten their fill and had started up the bench to lie around and watch their kill, a big cow moose.

Read Next: Coydog, Coywolf, or Coyote? A Complete Guide to Eastern Canids

I had my gun across my arm, pointed forward, and didn’t waste a second. I threw it up and snapped a shot at that frozen wolf. Don’t get the idea she stood there long — all this happened in an instant. That hurried shot missed; the wolf was so close I just figured I didn’t have to aim! She whirled and dived into the willows, and as she did, I saw that a front leg was missing.

I scrambled into a sitting position, lined up on a big black running downhill, and fired. It swapped ends, and landed with a whunk. Next I put the sight on another black about 50 yards off, and sent him rolling. He stopped, limp, against a line of willows. I missed a little wolf that was streaking away, but a second shot caught it in midstride, and it skidded 20 feet before piling up against a low bank.

The wolves were slow, their bellies full of fresh moose meat, and I had them dead to rights. I only vaguely remember the rest of the shooting. I just swung the gun on this wolf and that, the closest first. When they got a long way off, I’d take careful aim and shoot. Sometimes I’d see a geyser of grass spurt ahead of a wolf, and the animal would whirl broadside and stand still for an instant. If I didn’t kill it on the second shot, it would run to where some others had ducked into the willows. The farthest away — a good-size gray — was diving for the willows just as I lined it up. The gun cracked, there was a yipe, and willows closed over it.

When the battle was over I’d fired 21 shots and could see eight dead wolves scattered across the tundra. Then I remembered the gray one.

I had a hard time finding the place, but after zigzagging at the edge of the willows for a way I found a blood trail, and started following it. I’d gone about 20 yards when I saw the bushes moving ahead of me. Apparently the animal had lain down until I came along, and now was trying to get away. I hurried after it, and the animal speeded up too. Finally I lost sight of the movement and had to go back and pick up the blood trail.

Bit by bit I found where the wolf ran through the willows, came out the other side, and had gone across a tussock flat. I followed right across the flat and up a hill. Judging from the amount of blood I found there, I was certain I’d made a body shot — a solid one — and didn’t expect him to go far before he bled to death.

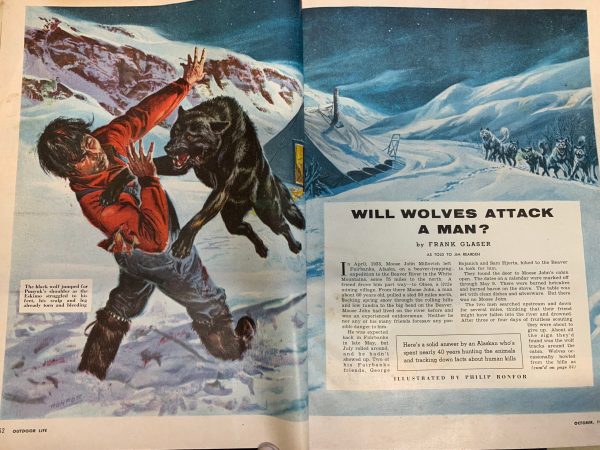

The trail led to a lone clump of willows on a high knoll. It was a patch not over 25 or 30 feet across, but very dense and with dead leaves still hanging. I didn’t think the wolf would stop there, but I was beginning to wonder. I walked toward the willows, my gun forward, safety off, and just as I started to par the brush the gray brute, lips curled back and mouth agape, roared and lunged at me. I pulled the trigger; he dropped within a foot of my moccasins.

I dragged him into the open and found that my first shot had broken the bone and slashed an artery just above the hock in the hind leg. His teeth showed him to be a young wolf — whelped the previous spring. He was big though, close to 100 pounds. Why had he turned on me? I think he’d just given up — a young wolf doesn’t have the guts of an old one. I believe an older wolf would have kept going until he died. This one wasn’t lying in wait for me, but had just quit there, facing his back trail, and I’d blundered right into him. He would have bitten me, though, if I hadn’t fired when I did.

Read Next: Frank Glaser Stopped a Charging Grizzly with his .220 Swift

That made nine wolves I’d killed out of that bunch. I dragged them together, built a fire, and started to skin them. The job took me nine hours and it was after midnight when I staggered toward home with that load of prime pelts. A few months later a ranger killed a three-legged female wolf in Mckinley Park maybe five miles from where I’d missed that first shot. Both the gray I shot at and the one the ranger killed had the left front leg missing.

Though I enjoyed shooting and trapping wolves when I lived at Savage River, it was a deadly serious business with me. And I wasn’t doing it just for sport or furs. I wasn’t sorry to see Alaska’s wolf population drop a few years later, and I’m proud that I’ve had a hand in helping to keep them down since then. Some folks claim wolves weren’t the main cause of the decline of Alaska’s caribou herd. I can’t agree. When they talk like that I just ask, “Were you there when the caribou herds disappeared?” I was.