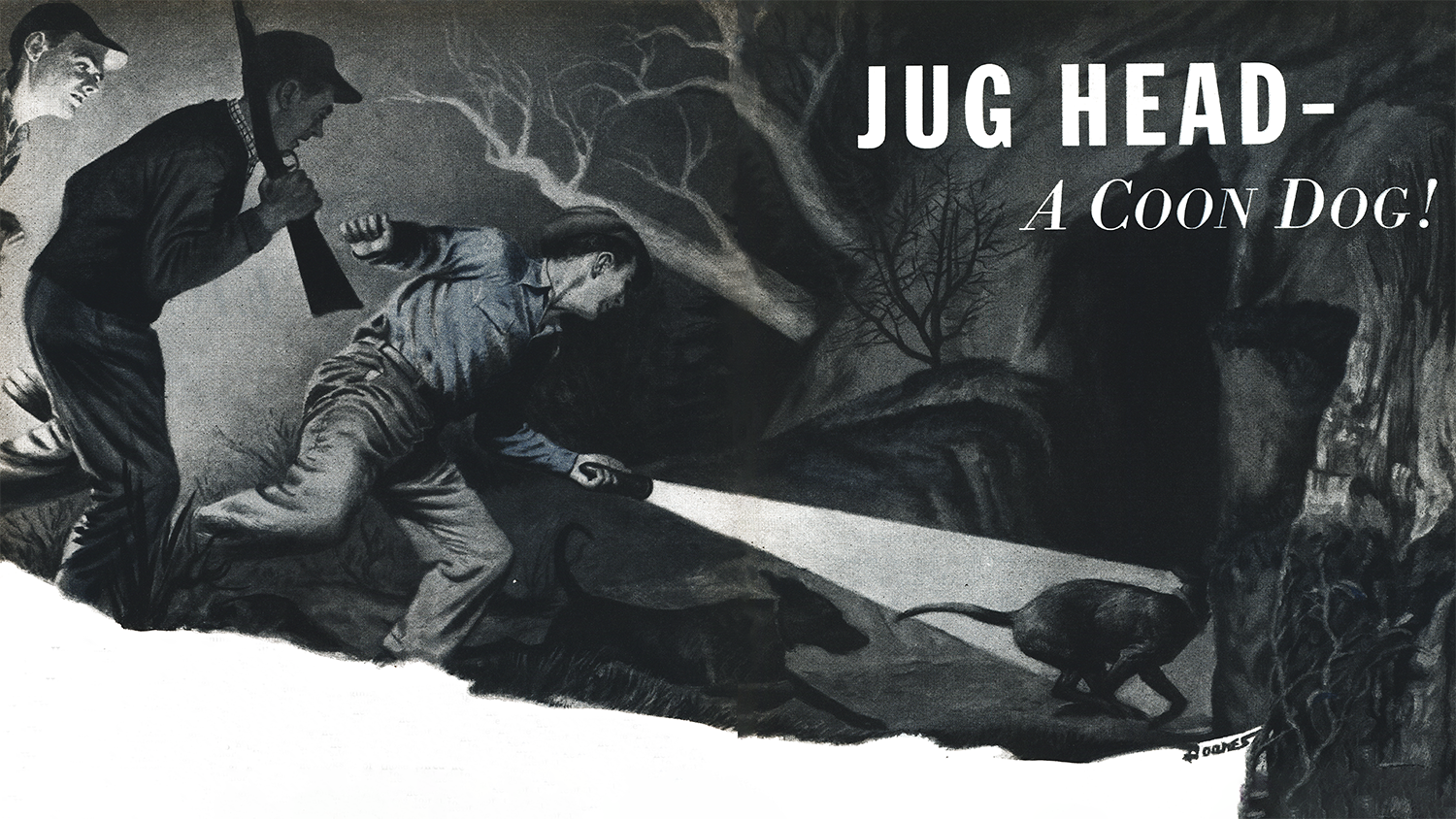

This story, “Jug Head—a Coon Dog,” originally ran in the January 1949 issue of Outdoor Life.

IT WAS MAC who brought the new dog home. We had argued for a month, he and George and I, as to whether we needed faster hounds or better luck. Mac insisted we’d never take the Wagonbox coon or any other like him with the pack we had—two redbones and two black and tans.

“You won’t run that coon down with any hound,” George contended heatedly. “He knows the country too well.”

We were hunting in Boone County, Missouri. Little creeks come into the Missouri River from ten to fifteen miles back in the hills, and where they cut through the bluffs they make rough and broken country. There is plenty of shelter for coon, lots of dense timber, and here and there are small caves known locally as sinkholes, some barely large enough for a groundhog to squeeze into, others big enough for cattle to loaf in while they fight flies.

Our coon chases were forever ending up with the dogs baying at a crevice leading down into one of those sinkholes. Or, if the cave was big enough, the chase came to an abrupt and sudden finish as the black hole swallowed up the dogs-and the clamor died away as suddenly as if somebody had thrown a blanket over them. For once inside, the coon always managed to squeeze through a crack he would find somewhere in the cave wall.

We caught a lot of coons, but the one we called the Wagonbox coon got away from us time after time. He was big and old and canny. He frequented the river-bottom cornfields near a big sinkhole known as Wagonbox Cave. Some ten feet high and eight wide, it went back into a hill for about forty yards, then ended in a sheer wall having but one tiny crack. From this crack a small spring flowed constantly.

Wherever we hit his track, the coon made it to the cave and to a crack in the side wall, halfway back from the entrance. In that impregnable shelter he had eluded us time and again.

Mac said the answer was faster dogs that would catch him on the ground or push him up a tree before he could reach the den. George and I maintained what we needed was a lucky break, in order to get between him and the cave and turn him back.

We had some lively arguments but settled nothing. Then, just before the coon season opened, Mac went out of town—and came back with a new dog.

He was a whizzer of a hound! Looked bluetick, Walker, and maybe something else mixed in. A slat-ribbed, swinging-eared, going-away dog if ever I saw one, only George and I wouldn’t admit it to Mac. I allowed we could get five bucks for him from some fox hunter, but George said he doubted it. “That pup couldn’t whip a fox if he caught one in a corncrib,” he jeered.

About that time the new dog, dancing red-tongued and panting on the clothesline that held him, dived for a passing house cat—and turned a complete somersault at the end of his rope.

“Why, you jug head!” George shouted and went into loud laughter.

Jug Head! The name stuck. Mac resented it a little, but he’d hunted with us too many nights to make an issue of it. So Jug Head became a member of our pack. He was just past two years old. And down inside, each of us hoped that at last we had found a super dog.

The first night Jug Head went to the woods with us he disappeared with the rest of the pack in the tangles along Hingston Creek. Shortly thereafter a strange yodeling bawl came streaking from an open stubble field.

“What did I tell you?” Mac yelped. “That dog can burn the ground!”

Then the chase ended as abruptly as it had begun. Everything got quiet. We headed for the place where we had heard the pup’s last bawl. We met Big Red, wise and seasoned, coming up from the creek. And then—Whew! What a stench!

The flashlight revealed Jug Head mopping the ground with the carcass of a skunk, while two redbones and a black and tan slunk away to more respectable pursuits.

Mac was glum and we were merciless. But he didn’t argue when we decreed that Jug Head was to stay on the chain till Big Red or Fanny opened on something legitimate. Mac trudged along downwind from us and suffered both mentally and physically as the impatient pup virtually walked on his hind feet against the leash.

Then Big Red’s long-drawn bawl floated across a cornfield. Big Red was honest and sure. The three other old dogs joined him within seconds. There was a brief burst of ringing hound music, then silence as they cast for the right end of the track.

Mac slipped the pup at the edge of the cornfield. All we heard from him was the crash of stalks fading across forty acres of unshucked corn.

Then Big Red rolled his discovery again. Three other voices chimed in, throaty and mellow. Almost before the last one spoke out we heard that eager yodeling bawl once more. In less than a minute it was way ahead of the rest, and turning back toward us through the cornfield.

Not sixty corn rows away Jug Head caught his coon. A big old boar, full of anger and fight. Jug Head couldn’t have killed him in a week but he was trying. The other dogs sailed in and made short work of it.

Jug Head caught another coon on the ground before the night was over, and George and I took the kidding from then on. But unlike Mac, we suffered in blissful silence. What’s a little skunk odor on a two-year-old dog who can overtake old coons ahead of four trained hounds that aren’t exactly slouches?

The next half-dozen hunts assured Jug Head a home for life. He caught more skunks. He opened on possums and crunched ’em in the pawpaw thickets before they had time to climb. And I actually saw him chase a rabbit, yodeling at every jump, till it slipped into a groundhog hole.

Big Red wouldn’t come to him, Fanny wouldn’t honor him, and we wouldn’t believe him either until one of the other dogs had verified his find. All the same, Jug Head was a coon dog. When one of the old hounds started a coon it was the pup with the ticks and spots on his lean hide who found in a hurry where the trail led. Mac and George and I knew we had a comer!

As Mac’s confidence in the dog grew, he kept suggesting a try for the Wagonbox coon. But George and I hadn’t admitted our growing appreciation of the pup, so we continued to ridicule the idea for quite a while.

We Couldn’t Hold Out Any Longer

Finally, however, there came a night in late November when George and I couldn’t hold out any longer. We told Mac to try it. “But if Jug Head runs a possum or a skunk tonight he’ll never go down with the old hounds again!” George threatened.

We drove out of Columbia on U. S. Highway 40 and headed up a side road. The old dogs pressed their noses against the windows of the jalopy and moaned softly. Jug Head did his customary dancing and scratching and kept up a continual whine. We grumbled and cuffed him, but there was no malice in our rebukes. For this could be the night!

We pulled up in an open place beside the creek. From here it was less than a mile straight over the ridge to the cave. Up the creek bottom and through the cornfields it was half again that far.

We lighted the lanterns and opened the door, and out tumbled our pack. Big, lumbering, steady Red; quiet, bugle-voiced Fanny; Bill with his jet-black coat and floppy ears; Drum, a hurrying, chopmouthed black and tan. And Jug Head. He turned a cartwheel at the end of his chain and bawled his eagerness. Mac swatted him with his old felt hat to shut him up.

We struck off up the creek bottom. The four old hounds ranged out ahead of us. Mac was leading Jug Head and the pup was straining so hard at the chain that his front feet barely touched the ground.

It was a coon hunter’s dream night, warm and still, and black as the inside of your hat. We moved along at a slow shuffle, talking sometimes in low tones but mostly just listening and waiting.

“Maybe he didn’t come down tonight,” Mac remarked at last, when we’d gone half a mile and heard nothing from the dogs.

“He’s down,” George said flatly: “If he’s not, on a night like this, it’s because he’s left the country.”

Jug Head was still lunging on the end of his chain, frantic with impatience, and sweat was running from under Mac’s hatbrim. George and I took pity on him and called a halt. George leaned the shotgun against a tree and we sat down on a big elm log. Mac took a turn of the pup’s chain around a nearby pawpaw bush. Jug Head bawled his disapproval and made a couple of lunges. A lantern overturned and the old shotgun went clattering down in among the leaves.

“Something sure has to give when that darned fool makes up his mind to go hunting!” George commented.

Mac was snubbing the pup to a bush farther away when off to the north, in the next valley a full mile from us, there came the sound we’d been waiting to hear—Big Red’s long, rolling bawl. Then Fanny’s high-pitched bugle sounded, and Drum and Bill cut loose, their voices muffled by distance and timber.

Jug Head squalled at Red’s first note, and for the few seconds it took for Mac to turn him loose he babbled as if something were eating him alive. Then he was gone, racing north toward the running pack without a sound.

For the next few minutes it sounded almost like a sight chase. Instead of swinging back toward the cave the clamor continued north until the dogs were nearly out of hearing.

“That’s not the Wagonbox coon,” Mac declared.

“If it is he’s ranging pretty wide,” George agreed. “He’ll tree over in the next valley.”

We were up off the log, ready to follow the hounds, when the chase turned. And as it turned we heard an eager squalling yodel. Jug Head was there.

The pack topped a low ridge and five distinctive hound voices echoed in the night, driving in a long circle back toward our valley.

We headed up the steep hogback toward the cave. Halfway up we stopped to listen. They were coming our way for sure, but it sounded like two separate chases now. One was led by Big Red’s rolling bawl, with Bill and Drum and Fanny crowding on his heels. But on a hickory ridge 300 yards ahead of them, Jug Head was running a one-dog race, his yodel hitting the night every quarter minute.

“They’re on a fox!” Mac declared, and George and I thought the same. They’d run more than a mile now. A coon can travel when he’s pushed, but not that far. If this was a coon it was one for the book. Our hearts were pounding more from excitement than from the exertion of climbing the ridge.

At last we panted out on the crest of the ridge 200 yards above the cave. Down the valley toward the mouth of that black hole the dogs were coming at a tongue-hanging clip. But Jug Head still had his lead. His yodel was shorter now and came less often. We heard him clear a fence into a close-cropped pasture 400 yards from the Wagonbox.

A Running Battle

Then it happened! Jug Head caught him! For perhaps ten seconds the quiet Missouri night rang with growls and squalls of rage. Then it broke up and a running fight started toward the cave mouth.

We charged down the ridge, stumbling and yelling encouragement to the game young hound. Big Red and his gang were coming on, disregarding the track, racing for the sounds of battle.

No other coon had ever given Jug Head that kind of scrap. Maybe he couldn’t kill a big one by himself, but this was the first that had been able to fight him off and run at the same time. “That’s no coon!” Mac yelled as we pounded the last fifty yards down the ravine to the cave.

Jug Head carried his running fight straight into the black hole. He was out of sight when we came up. We were just in time to see the other dogs streak in after him.

The muffled screams, yelps, and snarls that came out of the Wagonbox Cave were something to make your hair stand up! We heard a single terrifying howl of agony rise above the sounds of the battle, and then as we crowded into the cave entrance the fight broke off and the dogs were barking tree. There was rage and hate in their clamor, but there was a chopping cringing undernote of fear too, as if they could see their quarry, could almost reach it, but were unwilling to try.

The white beams of our flashlights stabbed into the cave, searching for the dogs. There they were, four hounds. Two redbones and two black and tans, on their hind feet, leaping and baying up the side of the cave.

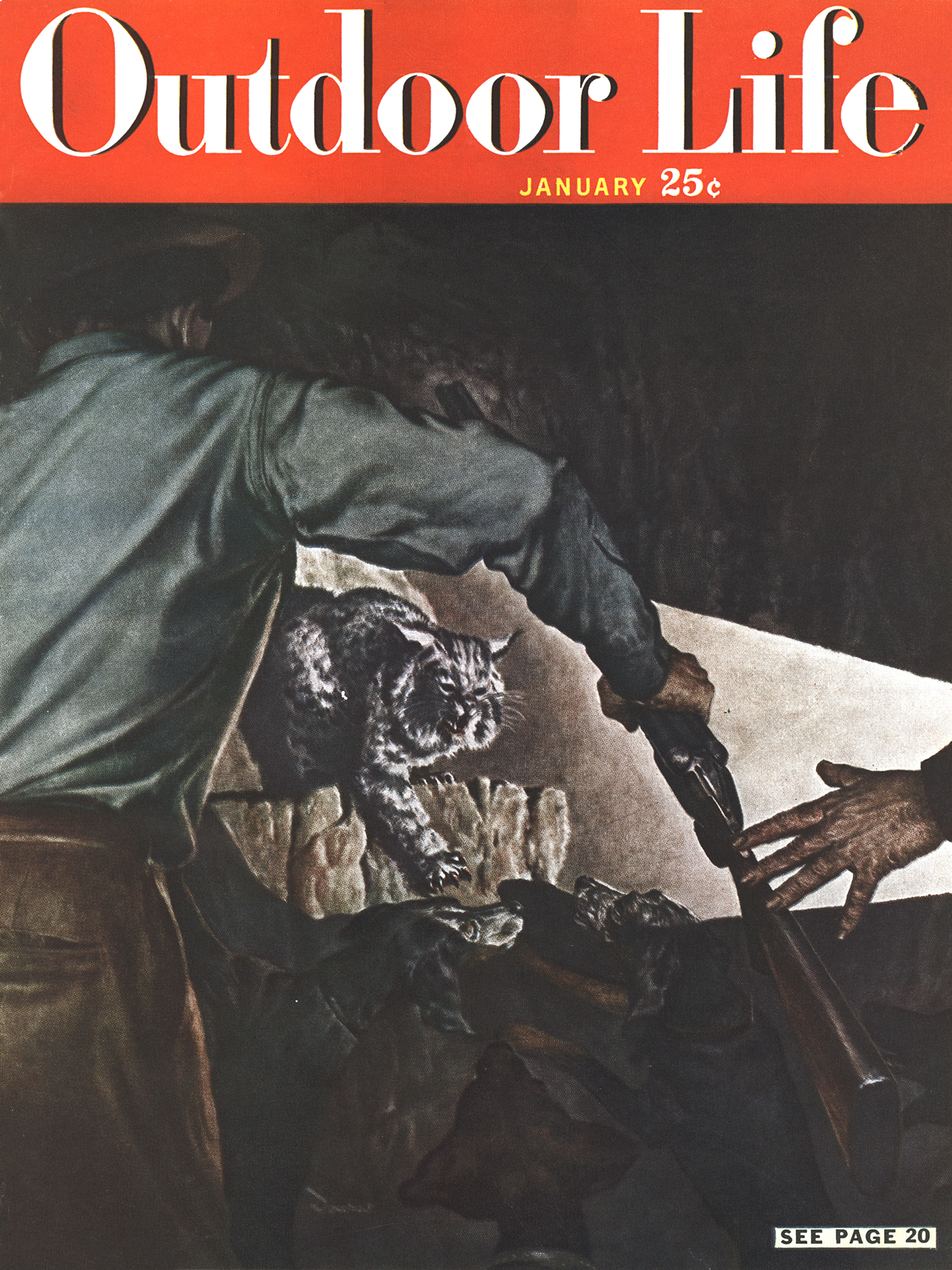

At what? My light probed higher and caught a green glint of eyes. There, on a little ledge, stood a big bobcat. His back was arched, his teeth were bared, his stub tail was twitching. He slashed down at the clamoring hounds with a long front leg, leaped back and slashed again.

Mac switched his light suddenly back to the floor of the cave, nearer our feet. A dog was lying there, a white dog with spots on his side and little ticks that looked like pepper patches in the glare. We couldn’t hear him for the baying, but we could see his mouth open and close in a howl of pain as he tried to drag himself toward us.

He couldn’t make it. Then we saw the long jagged hole in his belly.

Mac had jerked the shotgun away from George. A flash of fire stabbed toward the cat, a blast hammered our ears. Bobtail tumbled off the ledge and was smothered under a pile of tearing, ripping hounds.

There was just one thing left to do, and Mac did it. Then he set the gun against the wall and walked out of the cave.

If he said anything I didn’t hear it. We were all deaf anyway from the concussion of the two shots. George dragged the cat away from the dogs and started them for the entrance. I picked up the gun and turned my light on the still, white form on the floor.

Just a mutt of a hound. A purebred nothing. But a jug head? My eye. He’ll be a great hound in my book so long as the little stream trickles from the back wall of Wagonbox Cave.

This story has been minimally edited to meet contemporary standards. Read more OL+ stories.