“Big tracks don’t always mean big racks, but big racks always mean big tracks.” —Old deer hunter saying

“I’VE NEVER YET shot a big buck that didn’t have a big track. So a big track is key. You find a big track, and now you’re getting someplace.”

I listen closely to Michael Hirschi, even as my eyes wander incredulously across the handful of 200-plus Boone and Crockett mule deer mounted on the walls around him.

Michael and I have been friends for years. Yet awe still washes over me every time I see his collection of once-in-a-lifetime bucks. I’ve lived my life in some of the best big-buck habitat on Earth, and I’ve personally killed some big mule deer. I know many talented deer hunters, but Hirschi is different: He has a gift. His time to hunt is limited, but he’s the most dedicated hunter I know. He doesn’t own or pay to hunt private land. Despite all that—or perhaps in part because of it—he is, I believe, the finest big-buck mule deer hunter alive.

“I’ll keep looking, checking another area, and another, until I find a big track,” he adds. “And then I’ll key in on that area.”

I pry my eyes from those massive antlers and study my friend. He’s slightly above average in height and powerfully built, and he sports the small potbelly typical of athletic men in their 50s. He’s a good guy: generous, kind, and humble, and willing to help his friends and family who hunt. But you won’t find him talking hunting at the local convenience store. For him to tell you about his hunting spots requires years of unbroken trust. Monster mule deer are his passion, and he’s always thinking about where he might find the next one.

“We’ll be riding the four-wheeler down some remote desert two-track, flying along, me snuggled up and thinking we’re having this romantic ride together,” says Hirschi’s wife, Kristine. “Suddenly he’ll lock the tires up and we’ll skid to a halt in a cloud of dust. ‘I saw a deer track,’ he’ll say, and throw it in reverse. That’s how he is. Always focused.”

Focused is the only word for him. Hirschi hunts areas with such low deer densities that he’s gone up to six days in a row without sighting a single deer. Not many people have the mental fortitude to endure that kind of punishment. But it doesn’t faze Hirschi. Because on the seventh day, he just might spot his next monster buck.

Big Tracks in Big Country

So what is a large track exactly? This varies from deer to deer, explains Hirschi. A buck that lives in a rocky region will have shorter feet than a buck that spends his time in sand or grass. Anything more than 3 inches long is worthy of a second look, and a track in the 3⅜-to-3¾-inch range will usually come from a truly big, old deer. The track must be wide as well as long, which will give it a blocky shape—like something heavy made it. A big buck’s tracks will be wider apart than tracks left by a young buck, denoting broad shoulders and a thick, mature physique.

Once he locates a track big enough to pique his interest, Hirschi carefully considers his next move.

“I’m gonna ask myself, ‘Where does that track sit on the map to water, bedding, and feed? What is a deer going to do in that location?’” Hirschi says. “‘Where is he watering, and how often?’ Deer are habitual, and they will use a particular area more than others.”

Locating a big mule deer track and following it for miles across the desert sand, finally jumping the buck for a shot, is a vanishing and honored skill among mule deer hunters. Very few can accomplish it.

“An old hunter told me the story of this giant deer he killed,” Hirschi says. “He tracked it three days, slept on the track. Wherever night found him he’d just sleep right there. On the third day he caught up with the buck. He jumped the buck a bunch of times in between, but finally got the opportunity for a good shot.”

Hirschi explains that most bucks will usually circle back to the same place where you jumped them. If a hunter is smart, he can figure out the buck’s pattern before that happens—and use it to his advantage.

High bedders are the easier deer to hunt. Then you get the low bedders.

“Those are the tough suckers. A low bedder will lie down in the bottom of a wash, up against a cut bank, and you’ll never see him. If something comes up the wash, boom! he’ll blow up over the edge and run like the dickens. And he can run better than I can shoot, no question.”

So Hirschi will track a little way, then circle to try to spot the buck. If you don’t see him, relocate the track, get an idea of where he’s going, and loop again. Making that loop is important, especially if you are working alone.

That’s how Hirschi killed his first giant buck, at the age of 17. He jumped a big deer, followed the sign until he had an idea of his direction of travel, and then made a loop. As he eased in to his original position to reacquire the track, he spotted the buck. The mule deer was watching his backtrail and didn’t expect danger to come from the side.

A Master’s Plan

Any other hunter would want every advantage in his favor when pursuing a world-class buck. But about two decades ago, Hirschi made a decision to hunt only with a bow. He had become confident that if he could find a deer while rifle hunting, he could kill it. That didn’t sit right with him. But even with a bow, he remains improbably effective. Some big bucks do elude him for an entire season, and he never lays eyes on them. This simply fuels his fire. It means he has a deer to scout and hunt the next year. And he wouldn’t have it any other way.

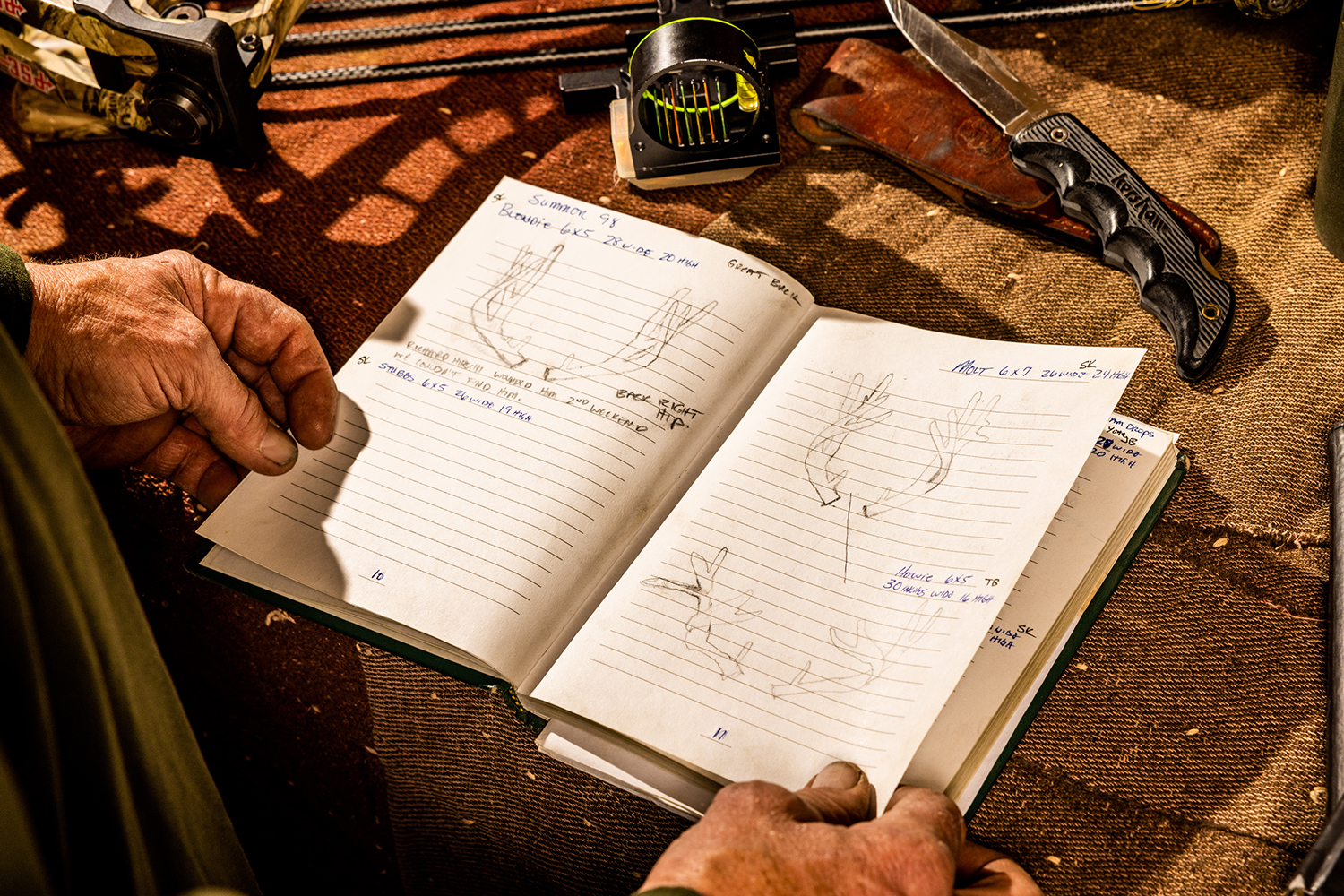

Once Hirschi does locate a big buck, he uses every tool at his disposal to get to know that deer. He’ll study satellite imagery, set trail cameras, follow tracks, and glass from a distance.

When hunting season arrives, he will search for the buck with almost indomitable will until he finds it. This can sometimes take days; the territory Hirschi hunts is vast, and these bucks can and do cover miles each day.

Most often Hirschi will follow a track only until it enters an area he can glass. That’s when he stops hiking and finds a vantage point from which to study the area with his binocular. He believes it is critical to glass several hours from a single position. It may take that long for a deer to move or for the shadows to change so that a deer becomes visible.

If, after several hours of studying an area through his tripod-mounted binocular, he doesn’t spot the buck, he will relocate and start over, glassing the area from a different perspective. Hirschi often goes days, weeks, or even years without finding a buck he’s hunting. The country is vast, and the deer density very low.

When he does find the buck, he’ll watch till it moves into a huntable position. Then he stalks in for a shot. Once in bow range, Hirschi doesn’t believe in trying to make a buck stand by tossing a pebble, or doing anything at all to draw its attention.

“When a buck gets that mature and old, he doesn’t make many mistakes,” he says. “More often than not, he will blow out and never give you a shot. So I just wait.”

I think about what that wait would be like, expecting a shot at a world-class buck any second for hours on end. Those moments are few and far between, says Hirschi, which means he never gets drowsy or lets his mind drift from the task at hand.

“I’m very alert, and there’s enough adrenaline flowing to keep me in focus. Wind is my main focus; I have to pay really close attention, so if the wind swirls or something changes, I can adjust. One moment nothing at all is happening. And one or two seconds later, I might need to make a shot.”

Big-Buck Country

Early that morning, we loaded into Hirschi’s pickup and drove into God’s country, the beautifully barren territory he hunts. We were there, ostensibly, to hunt coyotes. I think we both knew, though, that our main purpose was to connect with one of the places he loves best.

I’ve never been here, where Hirschi has spent countless days. Still, this place is important to both of us. To me, it’s a shrine of sorts. You can’t understand how incredibly difficult it is to hunt this country until you’ve been here.

My friend shows me how the bucks like to move and where they prefer to feed at certain times of year. He points out places he’s given names of his own. Each is enchanting: the Pasture, Heaven, the Gold Coast, Paradise, and Hope Town. They are names no one else would ever recognize. Which is important, because Mike Hirschi kills almost all his bucks on general-season, public-land units.

In his home state of Utah, private hunting land is rare, so hunters must compete with hordes of other public-land hunters. The hunting is tough, and most people will shoot the first buck they see. This makes it hard for a buck to reach maturity.

Further exacerbating the challenge of hunting public lands is the fact that tags are becoming increasingly hard to get. So any hunter who routinely tags monster bucks on public land is regarded as something of a superhero, a status that Hirschi never sought but possesses nonetheless.

Some hunters admire Hirschi’s accomplishments without jealousy. Other “hunters” try to shadow him—to find his secret spots—and beat him to the big bucks he’s hunting. So Hirschi is cautious about who he speaks with and what information he shares. He’s learned that lesson the hard way; several of his top spots have been spoiled by unscrupulous hunters who have betrayed his confidences.

The Legend of Clusty

We hunt coyotes, talk about deer, and finally end up back at the Hirschi place. My eyes drift again to one of the mounts behind him, a buck with otherworldly mass and towering antlers that stands at number 11 typical all time in the Pope and Young record books. Hirschi believes that had he managed to kill the buck one year sooner it might have been number one in the world, because that year his G2 and G3 tines would have forked much lower and measured significantly longer.

I wonder how a buck that big could possibly be any bigger. I also wonder if I could hold it together for a shot at one of these monster bucks, especially after investing years of scouting, days of glassing, miles of stalking, and hours of waiting inside bow range. Praying the wind doesn’t swirl. Hoping the buck stands from his bed. Anticipating a shot before darkness falls.

I’ve heard the stories. While hunting another of his bucks, Hirschi stalked within bow range of a group of bedded deer and waited the afternoon away. When the breeze veered, he backed out, then stalked carefully back into bow range, the wind again in his favor. The wind changed a second time, and again he retreated and repeated his stalk from downwind. Like a ghost, he sneaked into bow range a third time, and the group of bucks still hadn’t a clue. When they started to rise and stretch, he watched a buck feed past. The mule deer’s antlers were more than 30 inches wide and would score over 200 inches. Hirschi never drew. He was waiting for an even bigger buck that he knew was among them. Minutes later, he killed a 33¾-inch-wide typical-framed monster that gross green-scored 213 inches in velvet.

But the story I most want to hear is about the biggest buck that Hirschi ever hunted—one that’s not on his wall. A shadow crosses his face and, briefly, he tells me about Clusty.

Clusty, so named for the massive clusters of tines reaching skyward from each antler, lived early in Hirschi’s bowhunting career. He watched Clusty one summer and hunted him hard that fall without success. He saw the buck only one time the following year. Then Clusty disappeared. As far as Hirschi knows, no one ever killed him. He’s quiet, studying the floor.

“How big do you think Clusty was?”

Hirschi responds without hesitation. “At least 250.”

“TWO FIFTY!” The words burst from my mouth.

“Yeah,” Hirschi says. “At least.”

I can see why Clusty’s memory haunts him. Most hunters who tell you they have seen a 250-inch mule deer have just perjured themselves. Not Michael Hirschi. If he says a buck was 250, it was 250. Or bigger.

Divine Intervention

Still, there is something surreal about Hirschi’s ability to find and harvest bucks that are so incredibly above the norm. There’s no doubt that he works hard for this extraordinary success. But I want to know how he thinks about those accomplishments. So I ask him to what he attributes his extraordinary success at finding and harvesting monster deer.

His eyes grow bright as he sits at his desk, a collage of trail-cam photos still open on his desktop and perhaps 640 inches of bone spreading regally above the three shoulder mounts over his head.

“I believe that when God asked us to do specific things, he meant it. I’ve always tried to help or teach friends or kids who want to learn to hunt, whenever I get a chance. We are told that when we serve our fellow man we are in the service of our God. I do my best to fulfill that commandment.”

Hirschi leans back in his chair, his voice gravelly with emotion.

“We’ve also been commanded to set our own affairs aside and do God’s work on the Sabbath. I take that to heart, and I’ve committed to my heavenly Father that I will not follow my passion on his day. I’ve asked him to bless me in return.”

I lean back in my own chair. Hirschi works five days a week and has limited time off. Fifty percent of his weekend is a high price to pay. I suppose the agnostic perspective would be that Hirschi is simply a naturally gifted hunter who lives in trophy mule deer country. And if he hunted Sundays, he’d probably have even a few more bucks on his wall.

But then I really study the walls surrounding me, looking once more at the huge deer mounted there. I think back to the time Hirschi helped my oldest daughter harvest her own 208-inch buck. Then I look back at my friend, and remember everything that he has just shared with me. Some faith, it seems, should not be questioned.

—

Gear Hirschi Won’t Hunt Without

I asked Hirschi if there is anything he won’t go hunting without. He smirked and informed me that he doesn’t like to go without a bow or rifle. We had a good chuckle and then got down to business. Here’s the gear that Hirschi depends on every time he goes afield.

- BOW: PSE Full Throttle, with a draw weight of 60 pounds. His advice? “Use whatever bow you can shoot accurately and consistently. Shot placement is more important than poundage.”

- REST: Whisker Biscuit. Despite derision that it’s a beginner’s rest, Hirschi believes the Whisker Biscuit to be “the best bowhunting rest ever developed” because it’s bulletproof and quiet, and it keeps the arrow secure during stalking and waiting.

- SIGHT: Black Gold Ascent Custom Adjustable seven pin. Hirschi sets his pins at 10-yard intervals beginning at 20 yards and ending at 80. Then he relies on the adjustable feature on his sight to dial for even longer shots. Under ideal conditions, Hirschi is lethal to 100 yards with this setup.

- ARROWS: Victory VF TKO, 300 spine, cut at 29 inches.

- BROADHEAD: Grim Reaper 100-grain 1⅜-inch Razor Tip. Hirschi has used these broadheads since 2008 and has complete confidence in them.

- OPTICS: Along with a Leupold rangefinder and a sturdy tripod, Hirschi relies on a Swarovski 15×56 binocular with a tripod adapter and a Swarovski 20–60×80 spotting scope.

- OTHER GEAR: Leatherman multitool. Hirschi carries a 4-inch model and uses it constantly to measure deer tracks, repair gear, cut with the blade, or trim limbs with the saw. —A.v.B.

This story originally ran in the Diehards issue of Outdoor Life. Read more OL+ stories.

How to Listen to Season 3 of the Outdoor Life Podcast

- Listen to Season 3, available now, on Spotify, Apple, or wherever else you listen to your podcasts. Seasons 1 and 2 are also available.

- Tune in every Wednesday for new episodes of Season 3.