A new study from Utah shows that the state’s elk are feeling the pressure from hunters and responding accordingly. Conducted by Brigham Young University and published last month in the Journal of Wildlife Management, the study found that elk in central Utah reduced their use of public lands by over 30 percent by the middle of rifle season.

“Elk respond to changes in human activities, and are adept at seeking refuge from hunting pressure,” the study points out. But even more importantly, the study found that increasing hunting pressure on private land significantly reduces this “refuge effect” and effectively pushes elk back onto public land.

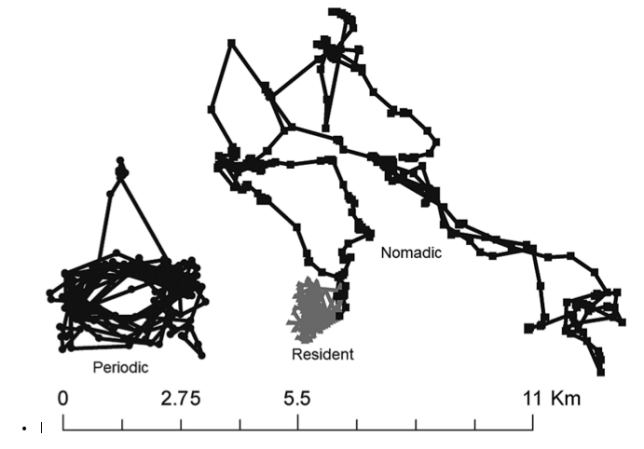

With funding from the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Sportsmen for Fish and Wildlife, and the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, the research project began in 2015. Between January of that year and March 2017, researchers and students with BYU helped the DWR capture and collar 445 male and female elk along the Wasatch Front in central Utah. The team then tracked these animals over the next three years and detected noticeable shifts in elk distribution from public lands to tracts of private land during archery and rifle seasons. And every year, like clockwork, the collared elk would shift back to public land at the conclusion of hunting season

“It’s crazy; on the opening day of the hunt, they move, and the closing day they move back” Brock McMillan, a BYU professor and one the study’s senior authors, said in a news release. “It’s almost like they’re thinking, ‘Oh, all these trucks are coming, it’s opening day, better move.’”

The timing of the study was also important because Utah began issuing private-land elk permits in 2016, and researchers noticed a marked difference in the distribution of elk over the years, which they attributed directly to the issuance of these permits. In 2015, the team’s GPS data showed collared elk at just 29 percent of public land locations. That number increased to 41 percent in 2016 and 42 percent in 2017.

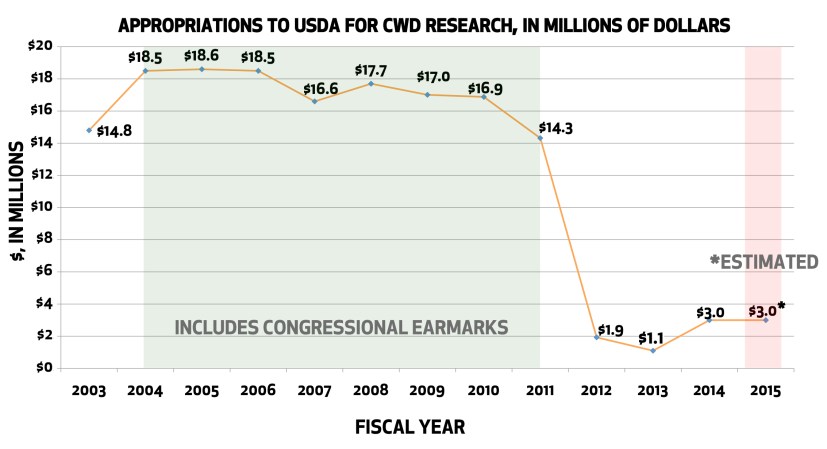

Read Next: If Chronic Wasting Disease Is Fatal, Why Aren’t We Finding CWD-Killed Deer in the Woods?

Taken together, these numbers show how private-land permits have allowed the state’s hunters and landowners to better co-manage its elk populations—while at the same time making more elk available to hunters on public land. As a result of the study, the Utah DWR has now permanently implemented private-land permits for elk. So while it may seem counterintuitive, the science shows those private-land tags help public-land hunters who have historically lamented the lack of elk on public lands during hunting season. And it’s a win for the state’s private landowners, who have long complained to the DWR about elk herds damaging their livestock and agricultural operations.

“Allowing private-land elk hunting in collaboration with private landowners has helped Utah keep these elk populations in balance with their habitat,” said Maksim Sergeyev, the lead author of the study. “Now there are more elk on public lands when the hunt starts and less elk on private lands negatively impacting industries and habitats.”