Even before the legal briefs and Lego blocks — more on that in a second — were tucked into folders and totes last month, word circulated that what just transpired in a makeshift Wyoming courtroom would have wide and deep significance.

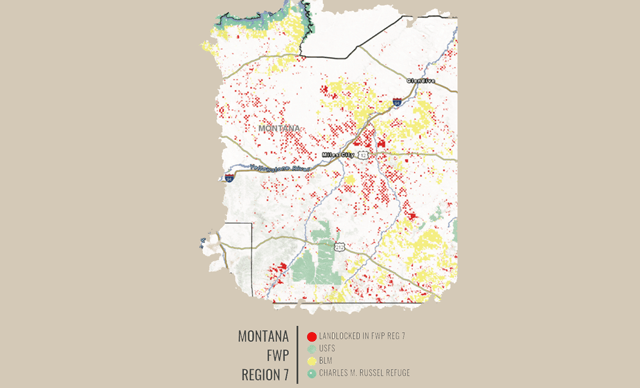

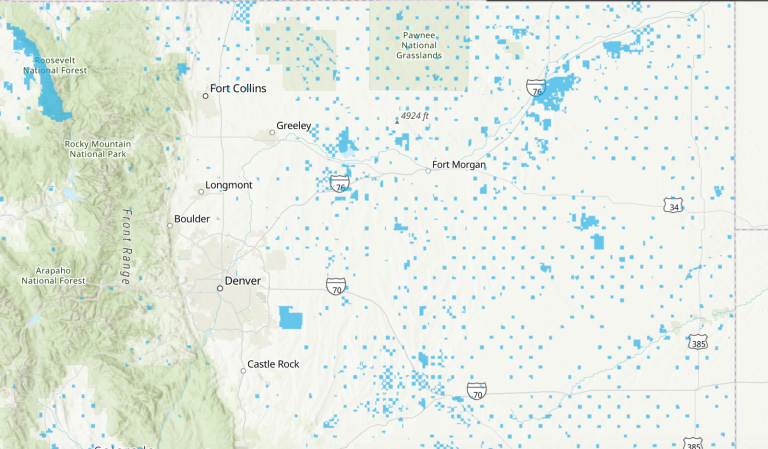

The case at hand was a criminal trespass trial involving four Missouri hunters who last fall used a stepladder to pass over the corner separating one section of public land from another in south-central Wyoming. As is the case involving some 8 million acres of land, mostly in the West, these blocks of public land are “corner locked,” or touch only at the vanishingly small point where their right-angle corners meet. They are otherwise surrounded by private land, which in the case of the Wyoming ranch where the incident occurred, is firmly off-limits to uninvited guests.

The owner of the ranch had the hunters cited for trespassing, the hunters pleaded not guilty, and the case went to the trial that culminated the last week of April with a six-person jury finding them not guilty inside a prefabricated building that temporarily houses the Carbon County Circuit Court in Rawlins.

The case was closely watched as a bellwether that could presage whether the same corner-hopping practices employed by the Missouri hunters would be legal to access corner-locked land in other states.

In illustrating how the hunters had violated the private airspace of Elk Mountain Ranch, owned by North Carolina businessman Fred Eshelman, Carbon County Prosecutor Ashley Mayfield Davis used Lego bricks to show jurors the concept of three-dimensional land ownership. One of the underlying concepts that kept corner-hopping in dubious legal territory is the curious notion that a landowner’s rights extend below the surface and into the heavens. According to that theory, which has foundations in old English legal tradition, it would be illegal to pass over private land, even though you might not set foot on its surface.

But the Wyoming jury found that the Missouri hunters had no intention of trespassing on the adjacent private ground, and they took only two hours to acquit the hunters. However, shortly after the victory the hunters were served a summons to appear on charges from a 2020 in which they crossed the same corner. The county prosecutor has asked for these charges to be dismissed, according to the Cowboy State Daily.

A third case, of civil trespass, has been filed in federal district court. The outcome of that case may have wider implications because of the federal venue, but all these legal gyrations beg the questions: what’s at stake here?

You’ll hear varying opinions that support the conclusion that this was the precedent-setting case Western hunters were waiting for to crack open the millions of acres of corner-locked land from Washington State to New Mexico. Alternatively, you’ll hear counterarguments that this settled only the specific case before a low-elevation court in a single state.

Instead of speculating on the implications of the outcome, it’s more useful to consider the possibilities the case presents. In no particular order, here are some possible outcomes of the Wyoming corner-crossing case.

Legislatively Outlaw Corner Crossing

There is a vigorous debate happening in private-property circles that advocates for taking the corner-crossing issue out of the hands of juries and giving it to elected officials. Some are suggesting that legislators should standardize trespass laws. This end-around has shaky foundations, and some suggest that it would likely fail either in the legislative process or be found unconstitutional, depending on the venue. Either way, it’s likely to calcify hard feelings around this issue.

Make Access Permanent

The most exciting opportunity the corner-crossing case enables is accelerating various flavors of access agreements around the West. Most states already have some type of arrangement that pays landowners who provide recreational access to their private ground. Some are enabled through federal Farm Bill programs like Open Fields, which bundles Conservation Reserve Program payments with an access provision. Others are administered by states, such as Wyoming’s Access Yes program, Montana’s Block Management Program, and South Dakota’s Walk-In Areas.

One of the key provisions of the Great American Outdoors Act, passed by Congress last year to great fanfare, was that it guaranteed $900 million annually in Land and Water Conservation Fund money. That LWCF funding has traditionally been used to acquire access in its various forms, but to date, the BLM — the agency that manages the vast majority of those corner-locked public tracts—hasn’t spent a dime on perpetual recreational easements on adjacent private land.

Instead, the agency has directed the money for fee-title acquisition of property, a high hurdle for local buy-in because many politically conservative rural communities resist the idea of public agencies purchasing private land.

But recreational easements have great potential and represent the best tool available to secure access to public land with problematic access. They can be purchased on a relatively cost-effective basis, and because the easements go with the title, they provide permanent access even if state legislatures try to forbid corner crossing or the land ownership changes.

Revise Federal Land Appraisals

There’s a big problem with the execution of the second point above. That’s the federal government’s outdated appraisal system, one that devalues recreational access. According to sources, the government appraises access at about seven cents on the dollar compared with the boost that recreational access gives similar private lands.

The feds are aware of that imbalance and addressed it in a Government Accountability Office review back in 2006. While some work has been done to modernize federal agencies’ assessment of the value of recreational access, I encourage Congress and agencies to take a fresh look at property valuations given the increasing recreational demands on public lands.

Encourage Land Swaps

One of the main problems with corner-locked land is the particular arrangement of checkerboarded private and public lands. What if mile-square chunks of public ground could be traded with adjacent private ground, creating large contiguous units that not only benefit public recreationists but also the landowners themselves?

Land swaps are notoriously hard to execute, because every property has its unique assets and shortcomings, and because land trades are based on equivalent assessed valuations and as we detailed above, there are structural imbalances in federal property assessments. Still, the prospect of peril shouldn’t frustrate the art of the possible, and federal agencies can easily neutralize the problem of providing difficult corner access by making those corners common ownership.

Contiguous blocks of public ownership accrue value with each additional section, just as contiguous blocks of private ownership gain in value without the intrusion of public recreators. Strategic land swaps would amplify their benefits to all parties, and LWCF funding and other sources could help get some of these real estate deals across the line.

Alienate Landowners

The Wyoming case has brought out hard-liners on both sides of the private and public-property rights communities. Public-land advocates are ready to push solutions — including condemnation proceedings — to gain access to corner-locked land, a nuclear option that would likely alienate landowners and create hard feelings between recreators and landowners, whose ground provides critical habitat for wildlife.

Hard-core private-property advocates are also lining up to take the issue to legislatures, Congress, and anywhere else they can affect the legislative and judicial processes.

Both sides need to acknowledge that there is good and important work to provide access that’s been happening long before those Missouri hunters deployed their stepladder. Hunters need to find ways to acknowledge those landowners who have allowed corner-crossing in the past. And landowners need to recognize the responsible behavior of hunters who have been respectful and restrained in achieving their access.

Randy Newberg, whose podcast drills into the history and solutions for corner-locked lands, is excited by the visibility the Wyoming case has brought to the issue. But he says there’s too much at stake for the hard-liners on both sides to control the dialog.

“For me, this comes down to a simple question: Do you want to fight or do you want to lead? I want to lead on this, and I want to take the microphone from those who just want to fight about who is losing more in this argument because if we play this right, hunters have a lot to gain.”