We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

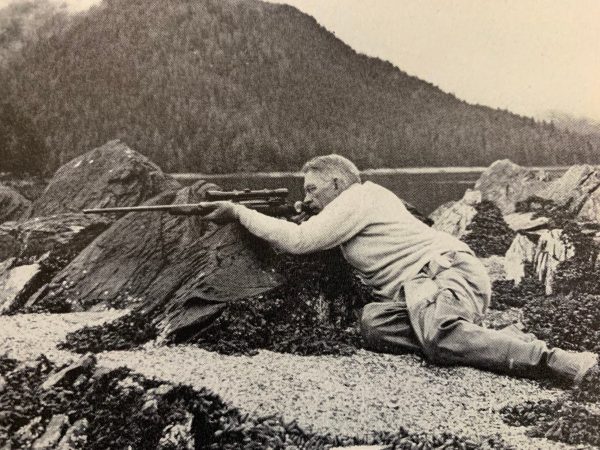

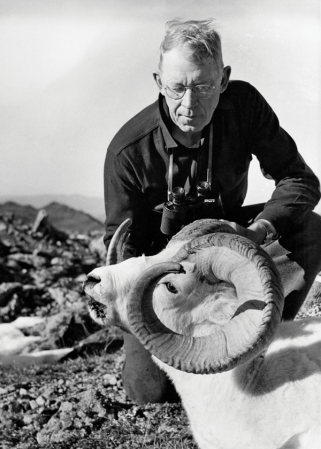

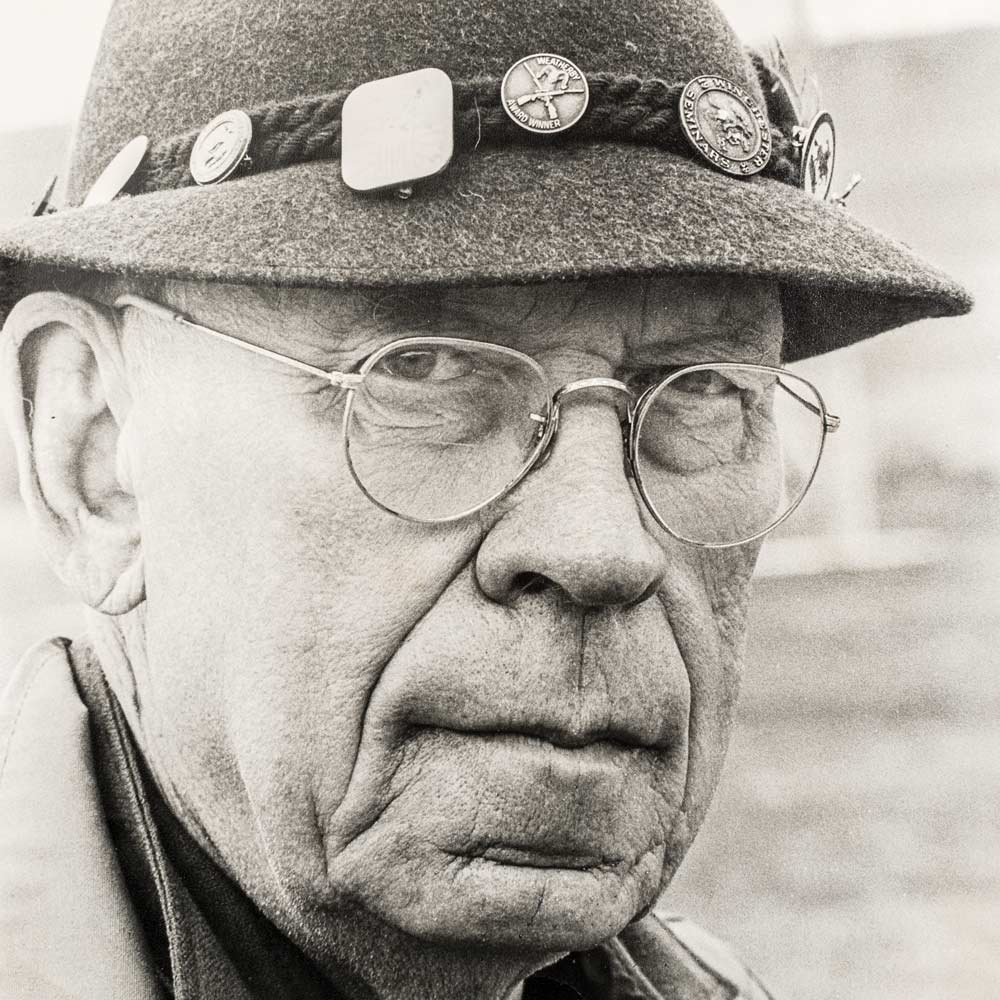

Today, Jack O’Connor, sheep hunting, and the Model 70 Winchester in .270 are linked in our collective subconscious. It was not always that way. When he started the quest for his first desert sheep, O’Connor carried a 10 ½-pound rifle, a 26-inch-barreled .30/06 with a heavy German scope. In the furnace that was August 1935, he hunted Mexico’s Sonoran coast. Returning home empty-handed, he knew what a sheep rifle was not. Later that summer, O’Connor hiked Thepopoh Mountain in Sonora with a “slender little Minar-stocked 7x57mm Mauser with a 22-inch barrel, equipped with a Lyman 1-A peep sight.”

When he heard hooves strike shale and the crashing of rocks, he scrambled to high ground fast enough to see the back end of a going-away ram, centered the bead, and triggered a shot. The sheep slid out of sight, and O’Connor walked down to his prize.

In 1939, O’Connor was appointed new guns editor for Outdoor Life, and in 1941, he took over the Arms and Ammunition column. In those days, Coues deer and desert sheep were his passions, and a lot of rifles came and went through his hands.

By the end of 1946, O’Connor had hunted enough North American sheep to complete three grand slams, although the term had not yet been coined.

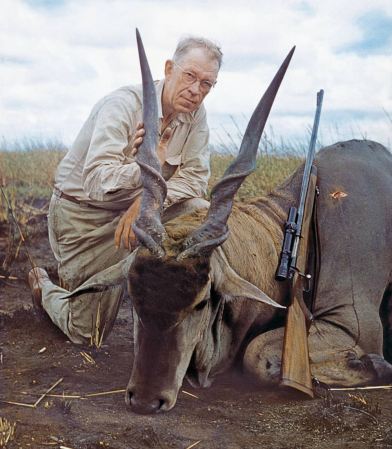

By 1954, he thought he had his ultimate rifle, a custom Model 70 in .270 Winchester that he had taken to Wyoming for elk, to India for blackbuck, and to Iran for red sheep and ibex.

He liked the rifle so much, he called it his No. 1 and set out to build a second to give his favorite a break from testing new bullets and developing loads.

With today’s wealth of rifle offerings, it is easy to forget that in the 1950s, a hunter who wanted an accurate rifle that was comfortable to carry, easy to handle, and capable of precise shooting had to have it built. Many of the guns people carried were sporterized versions of the weapons carried in combat a decade before.

The bolt-actions available on dealer shelves today that conform to what we think of as the American classic were informed by O’Connor’s choice in rifles. His proving grounds were the mountains of Alaska and the Yukon, and the desert, hunting Coues deer and desert sheep. The look is defined by a walnut (or synthetic) stock with a straight comb to align the eye with a scope, graceful curves, perhaps a cheekpiece, and a pistol grip that is somewhat oval in cross section and checkered to give a firm hold.

“A good sporting stock should enable the shooter to get a shot off quickly and accurately, and it should also be a thing of beauty,” O’Connor wrote in his book The Big Game Rifle (1952). “Many fine sporting stocks are handsome but of little aid in accurate shooting. Many others that hold and shoot well are homely and clumsy. The very best sporter stock design results in a stock with handsome, graceful lines and one which also enables the man behind it to do his best work.”

But the concept of the sheep rifle was still being refined in O’Connor’s mind and, for the world to read about, in the pages of Outdoor Life.

Sheep Rifle No. 2

O’Connor was 57 years old when he walked into Erb Hardware in Lewiston, Idaho, and bought a new Featherweight Model 70 in .270. Out-of-the-box accuracy was rare, and this gun was exceptional. Surprised his new rifle was capable of minute-of-angle accuracy, O’Connor took it to gunsmith Al Biesen to customize it.

Like his No. 1, this rifle also was stocked in French walnut, with a slim, pear-shaped wrist, and fleur-de-lis checkering recessed about ¹⁄₃₂ of an inch. The grip cap was engraved with a moose head. On the butt was a trap-style plate engraved with a ram. Turning the gun over revealed an unadorned steel floor plate, its release lever inside the bow of the trigger guard.

The jeweled bolt slid back and forth in the action, smoothed by a master machinist’s touch. The bolt handle was checkered to give it texture in the heel of the hand. It carried a Leupold Mountaineer 4X scope fixed in Buehler mounts. The rifle weighed 8 pounds and fast became his new favorite, dubbed Sheep Rifle No. 2.

The No. 2 went to Botswana with O’Connor in 1966, and he hunted with it in Spain, Iran, and Scotland. It accounted for a northern whitetail in Idaho and three Stone’s sheep in 1973, and O’Connor carried it on his last big-game hunt, in 1977. It remains in the O’Connor family and is on display at the museum that bears his name in Lewiston, Idaho.

In 2005, I met Bradford O’Connor, Jack’s son, at a Big Bore/Double Rifle competition in eastern Oregon. The rifle I had planned to shoot, a .458 Win. Mag., broke the scope mount in recoil, and O’Connor said I could borrow one of his dad’s rifles. He handed me a .375 H&H that had been to Africa and a second rifle padded in green diamond-tuck flannel.

“Take these over to the practice range and shoot them as much as you like,” Bradford said. “They were made to shoot.”

Inside the soft flannel gun case was O’Connor’s Sheep Rifle No. 2. In hand, the gun was light and lively, and the checkering stuck to my palms while the butt locked into my shoulder and cheek found its weld. My friend, outdoor writer and rifle expert Chub Eastman, was with me, and we both fired the famous Winchester. We kept a couple of empty cartridge cases.

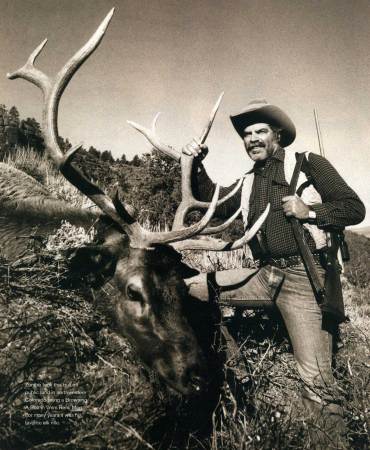

Jack O’Connor had a reputation as a prickly intellectual. He held a low opinion of his fellow man in general, but he was accessible to his readers, answering thousands of letters over the years. In December 1957, a cowboy from Joseph, Oregon, wrote to O’Connor. Verne Anderson had just acquired a Winchester Model 70 and wanted to know O’Connor’s opinion on factory loads then available for the 150-grain bullet.

While Anderson was fine-tuning his new rifle, O’Connor was refining the sheep-rifle concept. O’Connor went on to provide his favorite hand-load recipe.

Anderson’s Winchester is still in use, hunting the American West. The cowboy’s grandson, Kris Bales, employs O’Connor’s recommended load. The gun is sighted 3 inches high at 100 yards, the same as Sheep Rifle No. 2.

O’Connor came to learn that sheep could not be chased down from horseback, but instead were best hunted on foot, with a spotting scope on a tripod and a careful stalk for a close shot.

Today, when a hunter chooses a sheep rifle, it conforms to the pattern O’Connor prescribed—portable, handy, and relatively light. But specific design is left to the man or woman who will carry it up and over the mountain.

Read Next: Remembering Jack O’Connor

And this was the genius of the man who gave us the concept of the sheep rifle.

When going to the top of the world, where the hunt for rams takes us, we say we will carry a sheep rifle.

In that moment, when rocks roll down and a ram bounds from its bed, the rifle is light in hand, quick to shoulder, and quick to acquire its target. It is a thing of beauty because its every line aids in accurate shooting.

1. Author’s .270

- Year Mfg.: .1955

- Barrel: 24 in.

- Weight: 8 lb. 12oz.

- Optic: Leupold 2–7X

- Load: 150-gr. Nos. Partition

2. O’Connor No. 2

- Year Mfg.: 1959

- Barrel: 22 in.

- Weight: 8 lb.

- Optic: Leupold 4X

- Load: 130-gr. Nos. Partition

3. Anderson .270

- Year Mfg.: 1956

- Barrel: 22 in.

- Weight: 9 lb.

- Optic: Leupold 4X

- Load: 150-gr. Sierra BT