I can’t keep the crosshairs steady,” my hunting partner whispered. “The wind is rocking my rifle. Heck, I can barely see the buck in all this blowing snow. He must be 300 yards out.”

Such is deer hunting in the wide-open spaces of the Midwest, where distance and the weather must be mastered. We were experiencing what many of the prairie settlers described in their letters to East Coast relatives during their first winter on the Great Plains. The oceanlike prairie provides no buffer to the wind. This day snow was blowing at more than 30 miles an hour. Conditions were whiteout at times and the windchill dipped to 40 degrees below zero.

We would have been more protected hunting in the shelter of the wooded creek nearly a mile in the distance, but the buck we targeted had found shelter on the backside of a bare prairie butte. While the butte blocked the wind from him, we were on our bellies in the wide open and could feel the raging storm at full throttle.

Taking time to regulate his buck fever, my companion waited until the wind paused, allowing better visibility. Even with my earflaps down, the echo of the rifle was a shock, but the view through my 10X-power binocular told the final story. The buck crumpled in the snow.

Bailing Out

Although the prairie might seem to be so flat it couldn’t hide a housecat, it actually has plenty of preferred whitetail cover. Wooded rivers and creeks, brushy hillsides and cedar-choked draws dot the landscape from Texas all the way north to the Canadian provinces. Most whitetails seek out these traditional habitats, but hunting pressure can alter a mature buck’s view of such shelter. Hunters afoot and in trucks methodically hunt pockets of cover, pushing open-country whitetail bucks to new refuges.

Bucks that have lived through a few seasons often abandon traditional hiding places, even without pressure. Their maturity and experience tells them it’s time to get out. At least that’s how open-country expert Jim Nelson of Rapid City, S.D., sees it. Nelson has a passion for hunting prairie whitetails. Five years ago he purchased his own parcel of land and has become familiar with the bucks roaming within the ranch borders.

“The majority of the young deer, including the three-and-a-half-year-olds, use river and creek bottoms for sanctuary, but once a buck turns four and a half, he becomes a different deer,” explains Nelson. “Big bucks won’t use the cover where you’d think they’d be. They flat-out stop using it. Instead, they’ll go find some stupid little spot, some little finger draw with hardly any normal cover or trees. These spots are everywhere on the prairie and they’re effective hiding locations.”

After they’ve lived through a few hunting seasons, bucks learn that the biggest hiding places also are the ones that hunters check first. Once a buck reaches the age that he stops using obvious cover, you have your work cut out for you. The prairie is a huge stretch of land and whitetails have discovered they can disappear in the same small spots that harbor ringneck pheasants and sharptail grouse.

Locating the Hideouts

You’ve heard the old saying, “It’s like finding a needle in a haystack.” Trying to locate a buck hiding in the open can be just as tough. The prairie may look as barren as a desert, but take a hike across a 1,000-acre pasture. Rolling hills, wetland depressions, grassy knolls, eroded draws and weedy fence lines provide adequate cover for a buck. The federal government also helps whitetails hide through the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), which takes land prone to erosion out of crop production and returns it to grassland. Often the grass is dense enough to conceal a deer. CRP currently involves more than 34 million acres, most of it in the prairie states.

The chances of ambushing an open-country whitetail in such a vast space swing in the hunter’s favor if he can find and gain access to whitetails’ food and water sources. Although natural food is plentiful on the prairie, farmers have added to the mix with plantings of corn, milo, alfalfa, wheat and new varieties of soybeans that thrive in the semi-arid environment. Don’t overlook the lure of water. Flowing rivers and creeks provide much of a deer’s daily requirements, but it’s a good idea to keep an eye on small reservoirs and stock tanks fed by underground water lines.

While surveying for food and water elements, you’ll discover the main key to ambushing an open-country buck: does. Concentrations of does near ample food, water and cover will cause even a mature buck to make mistakes once the rut progresses. If does are feeding regularly in a field, a good buck will eventually show up.

After noting the lay of the land and observing deer movements, pinpoint the main hub of activity and then expand your search in progressively longer distances from the center. Mature bucks will feel safer bedding away from the main activity area, but they’ll stay close enough for daily visits. I’ve seen them hoof it more than two miles to be in the middle of the doe hangouts and food sources.

Quality optics, high vantage points and a tankful of gas are the key ingredients in locating bucks after discovering an activity hub. Don’t overlook traditional tactics either. Nelson recalls one hunt where he and a buddy were able to track a buck, which is uncommon in the prairie.

“Six inches of fresh snow dropped overnight. We found a fresh set of buck tracks heading across a huge wheat field,” Nelson recalls. “We followed the tracks by driving along the field for a while, but we lost the trail when the buck walked through an uncultivated patch that held grass twelve to fifteen inches tall.”

Nelson and his hunting partner stopped and got out of the truck to again find the tracks. As they were standing at the edge of the grass, the buck suddenly burst out of the patch to make a hasty retreat.

“If we hadn’t seen the tracks, I would never in a million years have thought to look for a buck in that small patch of grass in the middle of that big stubble field,” says Nelson.

Setting Up an Ambush

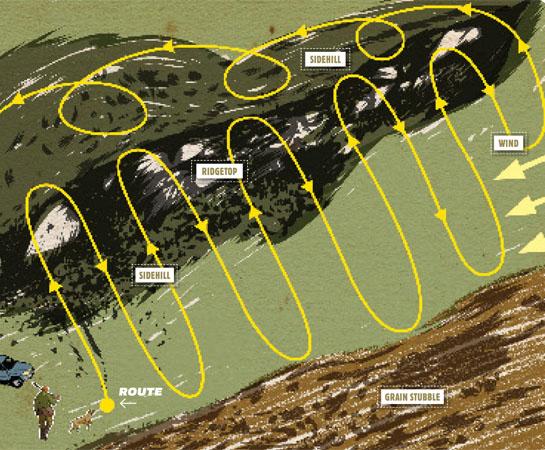

Having been raised in the prairie country, I’ve adopted some tried-and-true regional hunting techniques and invented a few others that have served me well. First, begin your hunt by glassing the surrounding country from an elevated position near an activity hub. If you can’t find a high hill, resort to a position in a haystack or even an abandoned barn.

After locating a traveling buck, study the terrain to see if there’s a way to intercept him using creek bottoms, rolling hills or fence lines as stalking cover. Most open-country ambushes require crawling to take advantage of available cover. I once crawled a quarter-mile to put myself into position for a shot on a prairie trophy.

If the terrain doesn’t allow for an immediate assault, file the location away and return for a morning hunt. Sneak into your position well before daylight to intercept the buck as he meanders back to his daytime sanctuary. Stay all day if you’ve located what you consider to be a trophy worthy of your patience. Be prepared to spend a few days studying a buck’s routine. Open-country deer frequently switch bedding areas, depending on weather, does or hunting pressure.

Nelson, a devoted bowhunter, likes to use ground blinds. He’s found that blinds don’t alarm deer if they are placed near round bales of hay. On his own property, Nelson leaves round bales out year-round in strategic positions so he can quickly erect a blind when a buck pattern is pegged.

Drives as a Last Resort

Spot-and-stalk hunting provides the best opportunities for the biggest open-country trophies. Organized drives usually generate a lot of action and some shooting, but drives don’t necessarily result in a lot of mature bucks being taken by any hunters in the group.

“In the last three to five years I have developed more respect for big whitetails,” says Nelson. “In the past we killed some of our big bucks by forced movement, often through sheer luck. It can be effective, but if you educate an open-country buck to how drives work, he’ll get wise quick and start using cover that is even less obvious to hunters. Or else he’ll move to the neighbor’s land and wait you out. I’d rather hunt a buck on his terms.”

Taking a wall-hanger in a land that favors his survival requires a stealthy hunter. As careful and safe as they seem to be in this open land, prairie bucks have weaknesses in their defense systems that an observant and adaptable hunter can exploit.

Long-Range Rifle Rigs

The open terrain of prairie country dictates the need for a flat-shooting rifle and a quality scope. Most hunters can whittle ranges to below 300 yards by using the cover on hand. If you plan to hunt open country, however, practice out to 400 yards and find your comfort zone.

Choose a caliber that delivers enough punch to knock down a 300-pound buck at long range. Here are a couple of suitable rifle/scope combos:

WINCHESTER MODEL 70/KAHLES 3.5-10X50MM: The Winchester Model 70 Black Shadow chambered for the .270 Winchester is a fine rifle that won’t break the bank. It features a blued black barrel with a composite stock.

The 130-grain .270 is a flat-shooting bullet with 9.8 inches of drop at 300 yards when zeroed-in at 150 yards. Depending on the load, the .270 produces upward of 1,600 pounds of energy at 300 yards with light recoil.

Top the rig with a Kahles 3.5-10x50mm with the TDS reticle system. This reticle-ranging system works with most factory ammunition. Hash marks on the reticle correspond to the average chest size of deer-sized game. To use it, put the animal between the marker bars that sandwich its frame snugly, aim and squeeze the trigger.

REMINGTON MODEL 700 BDL/LEUPOLD 3.5-14X50MM: You can’t beat the price or the performance of the Remington Model 700 BDL SS chambered for the .300 Remington Short-Action Ultra Magnum (SAUM). Top the stainless-steel-and-composite rifle with a Leupold Premier 3.5-14x50mm scope with its handy side-focus parallax knob.

The .300 Remington SAUM has a bit more kick than the .270, but you won’t feel it in the heat of the hunt. This caliber drops 9.7 inches at 300 yards when zeroed at 150 yards using a 165-grain bullet. At that range, it sustains a punch of 1,828 foot-pounds of energy.

Try to know the range before you shoot in open country. Equip yourself with a laser range finder like Bushnell’s Yardage Pro 1000. Range finders can back up reticle-ranging systems like those offered by Swarovski and Kahles. The Yardage Pro 1000 offers good readings to 500 yards on deer and is water-resistant.

Finally, invest in a pair of shooting sticks or a bipod. These are available from most shooting product outlets. Harris bipods and Underwood shooting sticks are both personal favorites.