Conflict with grizzly bears seems to be a daily occurrence in Western states this year. There’s a constant stream of headlines involving bear attacks, self-defense shootings, and government agents killing problem bears. One of the most recent stories is a 4-year-old sow grizzly that was killed by Grand Teton National Park officials after “repeatedly entering areas frequented by humans in search of food,” according to an article in Cowboy State Daily.

In case it’s not obvious enough, the article drives a hard point at the issue of food and the fact that this bear was getting it from the wrong places. According to the article, over the course of two years the bear had obtained human-sourced food, and become increasingly aggressive in seeking food from people, even causing property damage. According to the NPS, the grizzly had a litany of encounters in the past couple months and was ultimately captured and euthanized. It apparently started out getting into chicken and other livestock feed and quickly moved to garbage. The NPS uses the term “food reward” to describe human-sourced food that a bear obtains, whether that’s a pet, livestock, garbage, compost, or actual human food. The Cowboy State Daily article uses the same terminology.

I live and hunt in Alaska where grizzly bears are a part of many folks’ daily lives. Proper use and storage of foods, garbage, or other bear attractants is important in bear country, and it really can help save bears by preventing their acclimation to humans and a dependence on humans for food. But I think that the tendency to only focus on these issues—and not look at the bigger picture—is a mistake. Even the term “food rewards” seems to me to be ideologically blaming people for any incident where bears obtain human-sourced food. Sure, in a way, the bear is being “rewarded” with food for an action, such as breaking into a dumpster. But to me, the term paints the picture of the unwitting tourist tossing granola bars to a bear to get it to stand there for a photo.

Put another way, using the phrase “received food reward” in official reports implies that someone gave the food to the bear. In other words, no fault lies with the bear.

I don’t want to downplay the importance of the things we can do to avoid bear conflict, but some parties want to place the blame entirely on people. Another article published in Cowboy State Daily from August declares right in the headline that a man fatally mauled by a grizzly was found to be at fault, when no such accusations were even made in the official USFWS report on the incident. The USFWS report notes only that the attack was a result of the man ending up in close proximity to a moose carcass. It’s unknown whether that proximity was purposeful or accidental. Sometimes bears make bad decisions; sometimes people make bad decisions. Sometimes random events put people and bears in bad circumstances. Placing the focus entirely on human behavior ignore the elephant in the room: Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE) grizzly populations are increasing and expanding their range. That means they’re going to be coming into contact with humans more often.

With these increasing and expanding grizzly bear numbers, these conflicts aren’t going to go away—even with the most stringent food and attractant control. There will still be young bears venturing out and struggling to find food and survive. There will still be bears that make bad decisions and need to be euthanized.

I don’t think there’s been a better time to argue for regulated hunting of grizzly bears in certain areas of the Western U.S. It’s true that hunting wouldn’t exclusively target problem bears—they will always be an issue. I do, however, see a regulated hunt helping in two major ways. First, it can help with saturation. Removing some bears from an area that is near or above carrying capacity creates space for other bears. Second, it will increase bears’ fear of humans.

Opinions on this second point vary, and much of it is anecdotal. But from the many descriptions of encounters that Western elk and deer hunters have told me about, a common thread is that many of the GYE grizzlies simply aren’t scared of people. And why would they be? They’ve been protected and observed by humans at close distances for their whole lives.

I can’t speak from personal experience on the GYE grizzlies of the West. But I know that here in Alaska, even in some very high-density grizzly and brown bear areas that allow hunting, the bears want absolutely nothing to do with people. They run at the sight or smell of a human. This is true in the wilderness and in areas near human populations. It’s beyond time to start regulated hunting of lower 48 grizzlies.

It’s healthy for a bear population to view humans as dangerous. Grizzly bears are incredibly smart, and if they aren’t being pursued, many of them learn (probably from a young age) that humans are safe to be around. In areas where bears are hunted, they quickly learn that humans are not safe to be around.

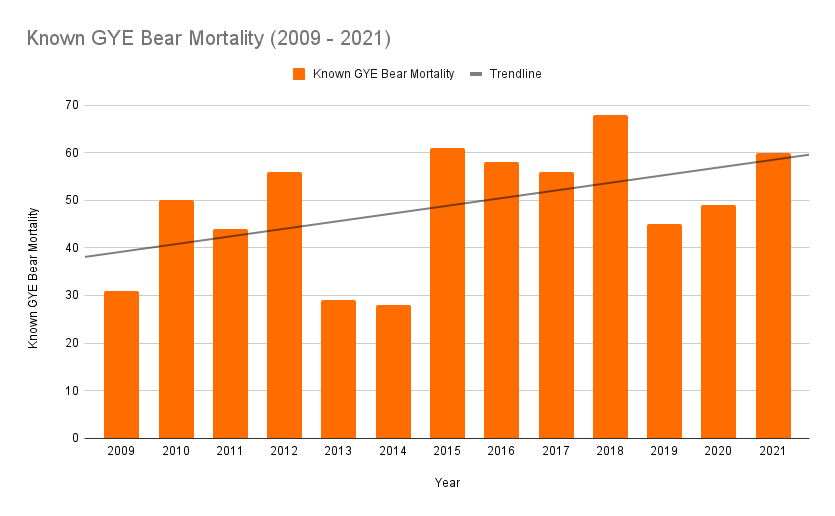

We all want to see a healthy population of bears existing in their natural habitat. Plus, following proper guidelines for how we store food and dispose of garbage is simply the right thing to do. But we can’t get sucked into believing that humans are at fault for every attack or problem bear out there. When grizzlies expand beyond their wilderness habitat, they will encounter humans. And inevitably those bears will be killed for it. According to the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team, more than 80 percent of known GYE bear mortality is caused by humans. While mortality varied from year to year—with 31 documented mortality incidents in 2009 and 60 so far in 2021—the overall trend is an increase in grizzly mortality.

There are practical things we can do to make the situation better. Allowing hunters to aid in bear management (as we do with so many other species) will benefit the bears—and the folks who live around them—in the end.