If you’re a fan of outlandish survival-themed movies and novels, then you already know how entertaining these fictitious adventures can be. The rugged wilderness settings and crazy plot twists can captivate our attention for hours, even though there’s something gnawing at the edge of our thoughts the whole time. It’s disbelief, and it rises from the fact that deep down – we know it’s a made-up story. No matter how much our disbelief is suspended by a great storyline, we know the tale never happened and it probably never would have happened. But these fanciful tales aren’t the only stories that authors and screenwriters can tell. There’s another kind of story that, if well told, can keep us on the edge of our seat and leave us marveling at the tenacity of the human spirit. These are true life survival stories, told by the people who lived them – and they are packed with real hard-learned wisdom. Here are just a few of our favorites, and some of the lessons they can convey to us.

The Story: On the night of January 29, 1982, Steven Callahan set sail alone in his small sailboat from the Canary Islands bound for the Caribbean. On February 5, the ship sank in a storm, leaving Callahan alone in the Atlantic in a five-and-a-half-foot inflatable rubber raft – naked, except for a t-shirt, with only three pounds of food, a few bits of gear, and eight pints of water. He drifted for 76 days, and over 1800 miles of ocean, before he reached land and rescue in the Bahamas. Callahan’s autobiographical account of the story, Adrift, is a gut-wrenching book which clearly details the extreme mental toughness required to survive at sea. And even though Callahan was alone, his mind divided into a “Captain” character and “crewman” character. The written log from the ordeal records a detailed fight over the water ration. The “Captain” won the fight, the rations continued, and Callahan ultimately survived.

The Takeaway: I often cite Callahan’s story when I teach survival classes, using his story to exemplify the strength of will you’d need in a long-term survival situation, especially if you are alone. But for me, the biggest example he set was one of adaptability. He spent over a month living on one pint of rain water a day and he was able to stay alive from only the food he could catch from the ocean (with very little tackle).

The Story: Most of us are familiar with the basic facts of the story: a plane with a Uruguayan rugby team on board crashes into the Andes Mountains; many onboard are killed, and after several weeks without rescue and a few failed attempts to walk off the mountain, the survivors are forced to resort to cannibalism. Nando Parrado, the hero and author of the book, Miracle in the Andes has provided a fresh re-telling of the high altitude plane crash through the lens of the person most responsible for the rescue of the survivors. The original story was recounted in the 1974 bestseller, Alive. Although he suffered a fractured skull, was unconscious for three days after the crash, and was presumed to ultimately succumb to his injuries, Parrado was able to revive. After several weeks of recovery, he eventually devised a plan and led a team over the 17,000-foot peak that trapped the survivors on a glacier, and marched ten days to rescue.

The Takeaway: One (rather grim) lesson we can learn from this story is to use all available resources (even if they are repulsive and unthinkable outside of the situation). This story also reminds me of the importance of getting out while you can. If some of the team had been able to leave the mountain top earlier, more people might have survived. Instead, they waited for a rescue that was never going to come.

The Story: 72-year-old Ann Rodgers of Tucson, Arizona was reported missing on March 31, 2016 by her family. After taking a few wrong turns on a remote dirt road in eastern Arizona, she ran out of fuel. To worsen the situation, she was out of range on her cellphone. Rodgers made the right move on night-one of her situation, staying with her car. She had extra clothing for warmth, and some snacks and water for sustenance. On the second day however, she made a decision which has killed many people over the past century – she left the vehicle to look for help. Had she stayed with the vehicle (as you should do), her ordeal would have been shortened by several days, since local police found the abandoned car on April 3. But aside from this major blunder, Rodgers showed remarkable skill and tenacity. Each night, she built a fire for warmth. She drank “pond water” for hydration. She even found edible plants along the way and a turtle which she roasted and ate for nourishment. Each of these skills, she claimed to have learned from a survival class and her continued research on the topic of desert survival. Rodgers told the authorities that she was angry with them at one point, since help hadn’t come. “I was frustrated, but I knew there were people who cared enough to make sure somebody found me…” But it wasn’t because local authorities weren’t trying. The local sheriff’s department and the Department of Public Safety were looking for her, with man trackers, scent dogs and aircraft. But again, Rodgers’ know-how came into play. She had made a large “help” sign from sticks and rocks, which a DPS pilot spotted on the ninth day of her predicament. Rescue helicopter pilot Lowell Neshem was quoted saying “I was completely shocked. Up to that point I thought we were looking for a body. I didn’t expect to find her alive.” After the helicopter set down and picked her up, Rodgers was flown to a local hospital and soon released.

The Takeaway: This story is chock full of teachable moments. Never leave the car. Bring supplies in your vehicle. Signaling for help can save your life. And finally, get some training! Rodgers credits a survival course for her amazing skill set, and she was clearly paying attention in class!

The Story: Juliane Diller (born 1954 in Lima as Juliane Margaret Koepcke) was the sole survivor of the 93 passengers and crew in the December 24, 1971, crash of LANSA Flight 508 in the Peruvian rainforest. The airplane was struck by lightning during a severe thunderstorm and exploded in mid-air. Koepcke, who was 17 years old at the time, fell thousands of feet still strapped into her seat. The thick deep jungle canopy cushioned her fall, and she survived with only a broken collarbone, a gash to her right arm and her right eye swollen shut. Koepcke had no training or gear, but her parents had once told her that the best way to find people in the jungle was to follow a waterway, since people often build camps and villages along the rivers. With no one else in sight, she struck out alone. Armed with only that bit of information, she was soon able to locate a small stream, which she followed for 9 days. She finally found a canoe and a nearby shelter, where she waited, and was soon rescued by two loggers.

The Takeaway: Luck can save you. And so can the right tidbit of knowledge. Without any survival skills or equipment, this brave young lady rescued herself – simply by knowing which way to go. Sadly, she was the only one to survive the event. Unbelievably, others had made it to the ground alive, their fall broken by the heavy vegetation. These survivors decided to await rescue, which didn’t arrive until weeks after the plane explosion. Koepcke’s mother was among this group – who all died of starvation and their injuries before searchers located the wreckage.

The Story: “No surrender!” That was the last order given to Second Lieutenant Hiroo Onoda, a Japanese army intelligence officer fighting near the end of World War II. Lieutenant Onoda followed his commander’s final order – for almost 30 years. Onoda did not surrender until 1974, spending almost three decades holding out in the jungles of the Philippines – under the belief that the war was still being fought. Onoda continued his campaign well after the war ended, initially living in the mountains with three fellow soldiers. As his fellow soldiers died or surrendered, Lieutenant Onoda refused to believe the letters and notes left for him that the war was over. He finally emerged from the jungle, 29 years after the end of World War II, and accepted his former commanding officer’s order. Onoda formally surrendered, wearing his hand-made, coconut fiber uniform, since his old uniform had long since rotted away.

The Takeaway: There’s something to be said for the “never say die” attitude of this dedicated officer. But let’s get serious. Three decades of your life wasted, playing hide and seek in the jungle with some very confused locals? This man’s tenacity is admirable, to a point. Once that point has come and gone, he’s simply wallowing in a quagmire of his own self-destructive stubbornness. If you can learn to tell the difference between tenacity and stubbornness, it just might save your life.

The Story: The Donner–Reed Party (often simply referred to as the Donner Party) was an infamous group of American pioneers who set out for California in an 1846 wagon train. Doomed by their decisions and delayed by a series of mishaps, the group was forced to spend the winter of 1846–47 snowbound in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Some of the party resorted to cannibalism to survive, eating those who had succumbed to starvation and sickness. The group became snowed in, near a pass in the high mountains in December of 1846. Their first help did not arrive until the middle of February 1847, almost four months after the wagon train became trapped. Two other rescue parties later brought food, and attempted to bring the survivors out of the mountains. Only 48 of the original 87 members of the party lived to reach California. Survivor Virginia Reed’s haunting letter to her cousin praised God for saving her life, and said “…we have all got through and the only family that did not eat human flesh. We have everything but I don’t care for that. We have got through with our lives but don’t let this letter dishearten anybody. Never take no cutoffs and hurry along as fast as you can.” May 16, 1847

The Takeaway: What a story! How about this for a respectful lesson learned, without the crude cannibal jokes? Don’t be in such a hurry that you throw caution to the wind. This group could have stayed alive and well – by waiting until spring to cross the mountains.

The Story: Forget the plot details of the amazing 2015 movie The Revenant (inspired by the Hugh Glass story). There was no dramatic shootout at the end of the story and Glass didn’t have a son to avenge. The real story is amazing enough. Hugh Glass was a mountain man on a fur trapping expedition in August 1823, led by Andrew Henry. During the expedition, Glass surprised a grizzly bear mother with her two cubs and received massive injuries. He managed to kill the bear with help from his trapping partners, Fitzgerald and Bridger, but was left badly mauled and unconscious. The expedition leader Henry was convinced that Glass would not survive his injuries. Henry asked for two volunteers to stay with Glass until he died, and then bury him. Bridger (then 17 years old) and Fitzgerald stepped forward and began digging his grave. Bridger and Fitzgerald incorrectly reported to Henry that Glass had died. Glass regained consciousness, to find himself abandoned, without weapons or equipment, suffering from a broken leg, the cuts on his back exposing bare ribs and all his wounds festering. Glass was mutilated and alone, more than 200 miles from the nearest settlement at Fort Kiowa on the Missouri. He set his own broken leg, wrapped himself in the bear hide his companions had placed over him as a shroud, and began crawling. Glass survived mostly on wild berries and roots. Reaching the Cheyenne River after 6 weeks of travel, he fashioned a crude raft and floated down the river, navigating using the prominent Thunder Butte landmark. Aided by friendly natives who sewed a bear hide to his back to cover the exposed wounds, Glass eventually reached the safety of Fort Kiowa. After a long recuperation, Glass set out to track down and avenge himself against Bridger and Fitzgerald. When he found Bridger, on the Yellowstone near the mouth of the Bighorn River, Glass spared him, purportedly because of Bridger’s youth. When he found Fitzgerald, and discovered that Fitzgerald had joined the United States Army, Glass purportedly restrained himself because the consequence of killing a U.S. soldier was death (though he did recover his lost rifle).

The Takeaway: This story is about one simple (and dark) human impulse – revenge. Hate fueled this survivor, though seemingly insurmountable circumstances. But that’s not the only motivation you can channel in dire emergencies. How about a positive motivation, like the desire to see loved ones again? That could fuel a survivor and put them in a better frame of mind.

The Story: Your plane crashes on an island full of cannibals. I doubt that scenario was part of the training that these airmen received. But when a U.S. Air Force C-47 nicknamed “the Gremlin Special” crashed into a mountainside in what was then Dutch New Guinea on May 13, 1945 – the survivors had to figure it out the hard way. The plane carried 24 officers and enlisted women. Only three survived, Lt. John McCollom was relatively unharmed, but WAC Cpl. Margaret Hastings and Sgt. Kenneth Decker were badly hurt. They soon found themselves in the middle of a native culture still untouched by the modern world. The natives were known cannibals, but luckily for the plane survivors, the natives mainly ate their enemy tribe. On July 2, 1945, after having spent forty-two days in the jungle, and unexpectedly nursed back to health by friendly natives, the three survivors and their rescue team finally escaped the island.

The Takeaway: Help can come in many unexpected forms during a crisis. The native people could have easily overpowered the surviving crew and had “long pig” for dinner. But since these people were “outsiders”, it’s likely that rules of hospitality came into play and these people were viewed as important guests, not a meal. They were unlucky to have been on that plane, yet lucky to have lived.

The Story: Five men left a Mexican fishing village on Oct. 28, 2005, expecting to go on a several day long shark fishing expedition. Their ill-fated voyage hit its first snag when they lost their heavy shark-fishing tackle. Then, the boat ran out of fuel trying to find the needed tackle. After shore winds pushed them further out, the current caught them, and held them in its grasp for nearly 5,000 miles into the deep ocean. During this ordeal, the boat’s owner, a man known as Juan David, and another fisherman, called “El Farsero,” died of starvation and were buried at sea. A Taiwanese fishing trawler spotted the boat and rescued the fishermen on August 9, 2006 near the Marshall Islands. Unimaginably, they had survived nine months and nine days lost at sea, making their struggle one of longest episodes on record for survival at sea. In the face of a slow death by starvation, the three survivors turned to their trade, fishing, to sustain them, along with the catching and eating of raw seabirds. The small group had some knives and other equipment aboard. And they fashioned hooks from engine parts and lines from cables to make up for the tackle they lacked. Salvador Ordóñez was perhaps the best prepared man onboard, as he brought his Bible, and had taken a course on surviving at sea a year prior to the incident. Ordóñez was given the nickname “the cat”, for his uncanny stealth at stalking seabirds, which would land on the boat at in the evening. Over the 9 month voyage, Salvador Ordóñez, Jesús Vidaña and Lucio Rendón spent their time fishing and praying. They also learned to live off raw fish and birds, and drink fish blood when rain was scarce. They weathered fierce fall storms, and prevented dehydration by drinking the rain. For entertainment, they sang ballads, danced as best they could on the small boat, pretended to play guitar, and read aloud from the Bible. Their most perilous times came in December and January, when several large storms hit and they were unable to fish, and in legitimate fear of sinking. Their longest stretch without food was 13 days with only one seabird to share among them.

The Takeaway: Upon their rescue, their hometowns and family greeted them as folk heroes, and their religious leaders hailed this story as proof of the power of faith. However you view this tale, it is a story of amazing seamanship and survival against the odds. But since this entire ordeal was preventable, I’d say this story is also a good reminder to bring some extra fuel when you’re out on the water.

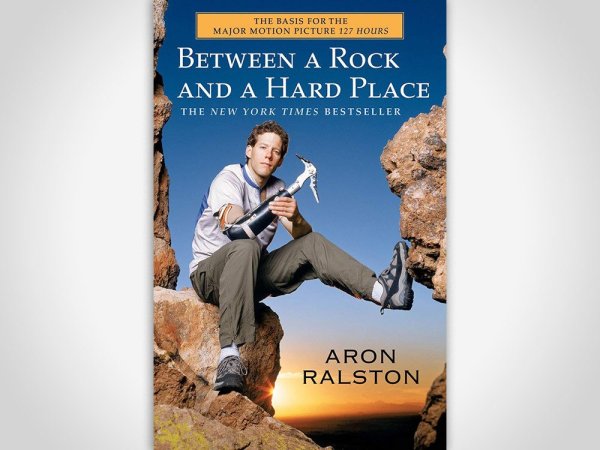

The Story: Outdoor enthusiast Aron Ralston became a widely known name in May 2003, when he was forced to amputate his right arm with a dull knife in order to free himself from the boulder that pinned it against a rock wall. Ralston was scrambling through a canyon in Utah, when a boulder shifted, pinning his arm to the canyon wall. He was alone, and no one knew where to look for him. He finally walked out of the canyon, near death and minus one arm. The whole incident is documented in Ralston’s autobiography Between a Rock and a Hard Place, and is the subject of the 2010 James Franco film 127 Hours.

The Takeaway: NEVER, and I mean NEVER, go out in the wilderness alone. I know, you need your space. But the buddy system has turned potential life-or-death situations into minor inconveniences since the dawn of time. Bring a friend. They can keep you company, they can help you if you’re hurt, and they can go for help if your arm gets pinned by a boulder. It’s also vital to tell someone where you are going and when you’ll return. This way, a search can be mobilized when you’re overdue and they will know where to start looking.

The Story: Just prior to the start of World War I, Sir Ernest Shackleton set out with his crew in an attempt to cross Antarctica on foot. But before the expedition was even able to reach the continent, their ship (the Endurance) became stuck in an early ice floe in the Weddell Sea. The crew of 27 had no means of communication or hope of outside help, and was to remain isolated for the next 22 months. The men lived within the bowels of the ship for almost a year before the ice destroyed it, forcing the expedition to move out onto the frozen sea. Several months later, the expedition built sledges and moved to Elephant Island, a rocky deserted spot of land just beyond the Antarctic Peninsula. At this point, no one knew what happened to the expedition, or where they were. Most people assumed they had been killed. Knowing that a rescue wasn’t going to happen, Shackleton made the decision to take one of the open lifeboats and cross the 800 miles of frigid sea to South Georgia Island where a small whaling station was located. Incredibly, he landed on the wrong side of the island and was forced to trek over the frozen mountains to reach the station. The Endurance: Shackleton’s Legendary Antarctic Expedition is a compelling book about Sir Ernest Shackleton’s failed attempt to cross Antarctica.

The Takeaway: Endurance indeed! These guys win the award for longest sub-freezing survival scenario. Shackleton’s leadership skills must have been superhuman, to keep his men alive and organize self-rescue – after nearly two years in a very frosty version of hell. Leadership can be a key survival skill, in both small and large groups.

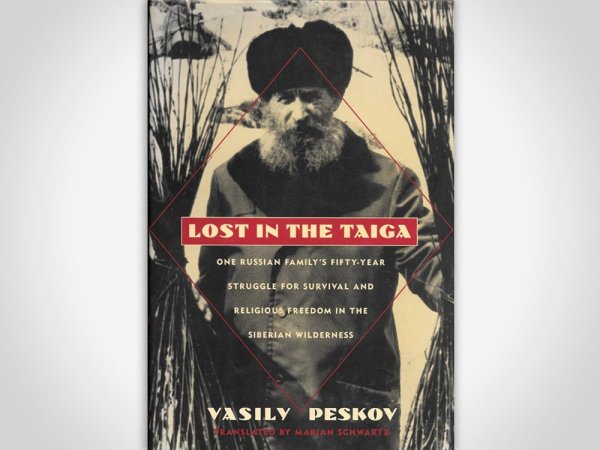

The Story: In 1936, a Russian family of four fled into the Siberian wilderness to escape religious persecution. Taking a few homesteading possessions and some seeds, Karp Lykov, his wife, Akulina, their 9-year-old son, and their 2-year-old daughter retreated into the forests. They built a succession of primitive huts as they traveled, until reaching a habitable spot near the Mongolian border. The couple had no contact with the outside world, and became completely self-sufficient. They had two more children, born in the wilderness, who had never seen a person outside their family until a geology team found their home in 1978. For sustenance, the family of six spent their days hunting, trapping, and farming by saving seeds each year to replant next season. The Lykovs had brought a crude spinning wheel and they grew hemp to produce the fiber for their clothing. Their staple food item was potato patties mixed with hemp seeds and ground rye. They lived this way, deep in the forests, for nearly five decades. The Lykov family survived in no small part due to their devotion to God and to each other. They also grew as much food as the land allowed and rationed it carefully. Each winter, the family would creep close to starvation, but they still held a council meeting to determine whether they should save their seeds to replant, or eat them all. Each year, the family saved their seed stock for the next season—even though one winter, it cost the mother her life.

The Takeaway: Teamwork and devotion are two central pillars in this story. Their devotion to each other and their religious views fueled them for decades in the wilderness. Their teamwork as a family allowed them to survive. Remarkably, the story hasn’t come to a close just yet. Even though she is an elderly woman now, the youngest child of the Lykov family still lives at their remote Siberian homestead today.