We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

One day in the summer of 1985, I wandered into a bookshop and found, tucked away on a shelf marked “Sports,” a book by Michael McIntosh. It was The Best Shotguns Ever Made in America, published in 1981, and it told the story of the legendary American side-by-sides: Parker, A.H. Fox, Ithaca, L.C. Smith, Lefever, and the Winchester 21.

The book was drawn from a series of magazine articles written in the 1970s, when McIntosh worked for the Missouri Conservationist. At that time, all but the Winchester 21 were out of production. For such a slim volume (just 185 pages), the book had an enormous impact. By recounting the stories of seminal, forgotten guns, it reignited interest in the American side-by-side in the hearts of many more. My own semi-dormant love of side-by-sides was rekindled.

Almost 20 years later, I was shooting at a skeet club with a friend who was also a lover of side-by-sides, when another member showed up carrying a Stevens 311, a long-barreled brute of a gun intended originally for geese at long range, or maybe grizzlies up close. A skeet gun it was not.

“You guys are always talking about how great side-by-sides are,” he said, “So I thought I’d try one.” We shot a round of skeet with exactly the results you might expect. Afterward, he shook his head. “Sorry, fellas, I just don’t see it.” It was no wonder. These two moments tie together and tell a lot about the American side-by-side market in general. It’s filled with contradictions.

In the years between the two, a lot happened: That reignited interest in side-by-sides of all stripes took off. Talk of resurrecting the great ones became reality: The Parker Reproduction of the 1980s was followed by the A.H. Fox in the early ’90s, and a few years later, the Ithaca Classic Double.

Meanwhile, prices of original Parkers in every grade soared, and they became a seriously hot item for collectors. The Fox, Ithaca, and “Sweet Elsie” (L.C. Smith) were pulled along in the slipstream. Magazines sprang up devoted to classic shotguns, along with side-by-side clubs, national shows, and shooting events. It appeared, for a time, that the side-by-side was back for good. However, appearances can be deceiving.

With hindsight, that couple-decades-long “renaissance” seems to have been a last flicker of interest before the side-by-side ran aground, yet again, on the shoals of economics and labor costs. Interest, while intense among the few, was just too small to support an industry.

However, Tony Galazan managed to build a substantial company on the back of that interest. Connecticut Shotgun Manufacturing (CSMC), in New Britain, began as a dealer specializing in old Parkers, cashed in on the explosion of interest in the ’90s, and brought the A.H. Fox back into production. Today, CSMC makes a boxlock side-by-side of its own design (the RBL) and has the rights to the Fox, Parker, and Winchester 21. He is also producing a new Fox shotgun for Savage Arms. No one in America knows more about the American side-by-side, than Tony Galazan.

Asked what he sees as the major obstacle to the sustained return of the American side-by-side, Galazan’s answer was not cost of production, rather surprisingly, but lack of demand.

“In the last five years, particularly, interest in the U.S. has centered less on the great old guns, and more on black guns,” he told me.

Looking back, it seems the great interest in side-by-sides that blossomed between 1985 and 2005 had a lot to do with nostalgia. Baby boomers, whose fathers and grandfathers shot such guns, had made some money and were now interested in acquiring a “good old gun like Dad used.”

The Parker Reproduction attempted to ride the wave of this interest, with guns made in Japan whose parts were interchangeable with the originals. They were produced in the most desirable gauges (20 and 28), in higher grades, with commensurate prices. The benchmark price was around $5,000. For the average shooter, that’s a lot of money even now, but it was huge in 1985. Although the shotgun press welcomed it, the buying public did not. Production ended after one or two runs, and the remaining stock of guns was sold off over the next few years at discount prices.

Galazan’s A.H. Fox is still in production, but likely would not be if he did not have a substantial company to back it up. The third attempt at reproduction, the Ithaca, was tried as a stand-alone company, with guns made in America. It lasted only a couple of years, produced few guns, and disappeared in a thicket of unpaid bills.

America’s original double-gun companies—Parker, Fox et al.—had all been swallowed up around the time of the Great Depression. Parker was absorbed by Remington, A.H. Fox by Savage Arms, and L.C. Smith, eventually, by Marlin. At various times, the famous names were attached to guns that bore little resemblance to the originals. In the 1960s, Savage sold a “Fox” that was, in reality, just a spiffied-up Stevens 311. Around the same time, Marlin tried to market a boxlock bearing the L.C. Smith name. None of these efforts bore much fruit.

Where the later attempts at reproduction failed was partly price—they were all expensive—and partly the fact that reproductions do not bear the collector’s cachet of originals. In the end, however, any shotgun design is going to succeed or fail on the basis of how well it shoots, and how well we shoot with it.

The market for side-by-sides in the 1980s and ’90s consisted largely of upland-game hunters. Yet, many of the old Parkers and L.C. Smiths were originally intended primarily as duck guns. They had long barrels, tight chokes, and too much drop. Since this was the beginning of the move to non-toxic (originally steel) shot, few people hunted ducks with them, and hunting grouse with them was a forlorn hope.

This was exactly the problem my skeet-shooting acquaintance ran into with his Stevens 311. According to Michael McIntosh, who chronicled the return of the side-by-side in both books and magazines, and wrote a volume devoted to the A.H. Fox, that company probably made more light upland guns than any of the others. But that aside, finding a quick, light double suitable for woodcock or grouse in any of the more common grades, from any of the great names, was tough. And since demand was high, the prices of those guns quickly climbed out of reach.

It’s an iron-clad rule of American industrial capitalism that if a demand exists, a supply will be created to fill it. In theory, with today’s computerized production equipment, it should be possible to produce a side-by-side every bit as good as those produced a century ago by the skilled hands of craftsmen at Parker and Ithaca. And, in theory, if enough of them were produced, the unit price could be lowered to put them within reach of the average shooter.

Why is it not happening? Simply because a genuine, check-writing, credit-card-swiping demand doesn’t exist.

Galazan has undertaken to produce, for Savage Arms, a run of guns to be called the Fox Sterlingworth. It is, Galazan says, a cross between the original Fox and his own RBL design, and he suspects it will sell for about $4,000. It’s hard to imagine Savage expects the gun to become a profit center. More likely, it will be a prestige item, just as the loss-making Model 21 was for Winchester for many years, and as Remington briefly attempted with the Parker more than a decade ago, before turning the rights over to Galazan.

More and more, it appears that the side-by-side shotgun, both American and European, is fated to become a niche item—the Morgan sportscar of the shooting world.

McIntosh once quoted an acquaintance who shot a round of clays with his own lovingly restored Wilkes Brothers game gun: “It’s like the first time you taste a really great wine,” the friend said, and he became an immediate convert. That, however, is rare.

Mcintosh himself was introduced to side-by-sides by his father; I learned about them in the pages of Gun Digest in the 1960s, whose writers assured me it was the choice of aficionados, and I’ve basically been a side-by-side man ever since. Only a tiny minority of new shooters today are likely to have a father who shoots a side-by-side; these rarely make the mainstream shooting press. And how many shooters will ever get the opportunity to field-test a London “Best”?

And there’s another consideration: In my experience, very rarely does a man or woman who learned to shoot a pump, or a semi-auto, or even an over/under, with a single trigger and a pistol grip, ever willingly switch to a double with two triggers and a straight grip. It all just seems too unfamiliar and even awkward. To really appreciate the virtues of the side-by-side, you need to be a shooter of some experience, not a beginner.

One ray of hope is that as interest in side-by-sides levels off, so will the prices of the thousands of American-made guns that are out there. They are not all priceless collectors’ items, and most have years of great shooting left in them, if only someone would take them out and put them to the use for which they were intended.

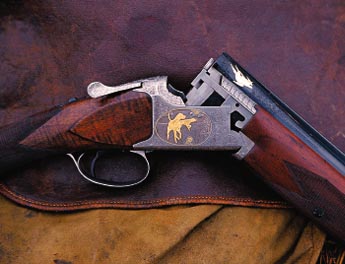

The right guns, in the right hands, will win converts, and then perhaps the whole cycle will start again. Because we can never escape one crucial fact: A fine side-by-side is a thing of beauty.