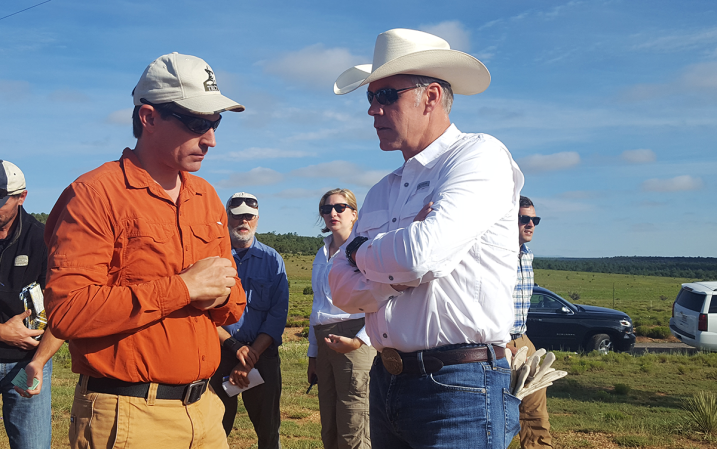

Scientists in Wyoming and elsewhere are demonstrating that healthy migration corridors are key for healthy big-game herds and robust hunting seasons. Secretary of Interior Ryan Zinke recently signed an order to put that science to work on the ground.

“This really is a science-based initiative,” says University of Wyoming associate professor Matthew Kauffman, who has helped broaden the understanding of how pronghorn, elk, and mule deer use the western landscape. “It’s a natural progression of what we have learned from research over the past 10 to 15 years.”

In particular, biologists have documented that some western big-game species commonly migrate 150 to 200 miles over the course of just one spring or fall season. That is comparable to more famous migrations of caribou in the far north or wildebeest in eastern Africa.

Earlier this month at the Mule Deer Foundation meeting in Salt Lake City, Zinke issued an order that western land managers such as the Bureau of Land Management and the National Wildlife Refuge system, use migration-data to help inform land management decisions and seek partnerships with locals to conserve these habitats.

“This is emerging as an important issue for sportsmen’s groups,” Kauffman said. “These long migrations illustrate why public land is so important for wildlife, but also how private land often provides critical connections between winter and summer ranges.”

Migrating big game learned their migration routes over thousands of years, enabling them to thrive in the rugged, arid regions of the West. Previously, biologists knew that wildlife migrated, but new GPS-monitoring allows them to pinpoint where the corridors are, how far animals go, and when they move.

For example, mule deer migration is not only key to surviving snowy winters, but also key to maximizing the amount of lush, nutritious forage the animals eat during hot, dry seasons. That pays off with more and healthier fawns. Freeways, fences, residential development, and oil and gas drilling can all impinge on a migration route.

“Until you map the corridor, it is hard to design an effective conservation solution,” he said.

Details – and funding – of Zinke’s order have yet to be spelled out.

For super-cool footage of migration corridors in action, watch the video below.

Warning: some of the big buck footage will make you drool on your keyboard.