On July 26, 1992, Billie Worthen watched the western sky fade to stars before unloading her rifle and leaving a herd of 876 sheep grazing in Spring Canyon, 8,000 feet above sea level in Utah’s Fish Lake National Forest. The guard dogs had the night shift.

When the sun came back around the other side, Worthen left her sheep house and rode her mare up to the herd. She was within a few hundred yards of the sheep when her horse began to spook. She soon discovered what was making her horse edgy–the smell of blood.

Hours later federal hunters with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Wildlife Services had to place rocks on the carcasses as they counted the bodies, to be sure they didn’t count the same animal twice. It was the worst single stock-killing incident in Utah state history–102 sheep dead.

Bending down to look at a track of the culprit, Kelly Joe Wright, a predator specialist, saw that the animal responsible for the carnage was a single mountain lion. He didn’t know then that this was the beginning of the reign of a new king on the Old Woman Plateau.

Mike Bodenchuk, currently the director of Utah’s Division of Wildlife Services, refers to Felis concolor simply as “lion”–not puma or panther or cougar or catamount or even mountain lion–just “lion,” as in the king of beasts.

Whether it’s king or not, when Bodenchuk accepted the post of regional director for Utah’s Division of Wildlife Services in the winter of 1993, he had little doubt that he and Wright would make short work of the mountain lion responsible for the bloodbath. Historically, few lions have lived long enough to earn a reputation, because when hounds or wolves get close, a mountain lion’s natural defense mechanism is to climb a tree.

But exceptions are unpredictable by definition–how was Bodenchuk to know his life was about to become intertwined with a lion’s?

A DEFENSIBLE KINGDOM

The tom’s territory was basically all of the Old Woman Plateau. Roughly 40 square miles, the plateau is jammed between I-70 on its western edge and a rim on its eastern edge, a 1,000-foot plummet that zigzags north like a lightning bolt. From the interstate the plateau seems shoved together under clouds hung low over a wild Rocky Mountain panorama. Up close, canyons appear and ridges rise. Distances triple and then quadruple as two dimensions grow to three, until all around is the kind of country that caused mountain men to linger.

Bodenchuk found the lion’s scratches at the borders of the plateau–leaves and dirt piled into a heap and urinated on to mark a territory. Male lions don’t get along with each other, and this stock killer was the dominant male. If a dominant male catches a juvenile male in his territory, he’ll kill him. If two big toms cross paths there could be a heck of a fight. After hunters, fights with other cougars are the chief cause of death of toms. Either this particular lion killed the dominant male that preceded him or a human did.

THE WAR BEGINS

John Wintch, a rancher who resides in Manti, Utah, held the grazing permit for the Old Woman Plateau, as his father and grandfather had before him. He hired herders to live from April through September in little white wagons and guard his flocks from lions, coyotes and bears.

On April 10, 1993, a herder found one of Wintch’s sheep killed by a lion.

There’s no mistaking a lion kill. Coyotes rip animals to pieces, like sharks in a feeding frenzy. Black bears maul their prey to death. But lions kill by biting the back of a sheep’s neck and twisting its head with a powerful forepaw to snap the spine.

After the prior year’s carnage of 102 sheep, this was what Bodenchuk was waiting for. Modern Wildlife Services hunters slay only stock killers and predators that endanger humans or recovering wildlife populations; they no longer use cyanide and bounties to indiscriminately exterminate populations of meat eaters. To be sure he killed the cat responsible, Bodenchuk had to wait for the cat to kill again.

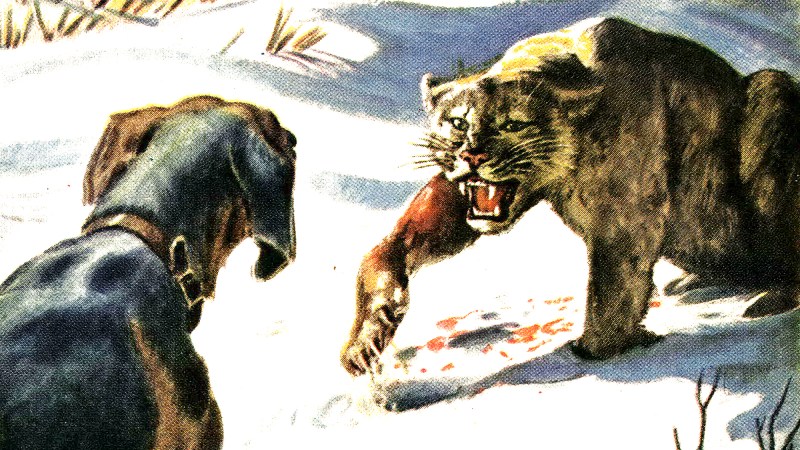

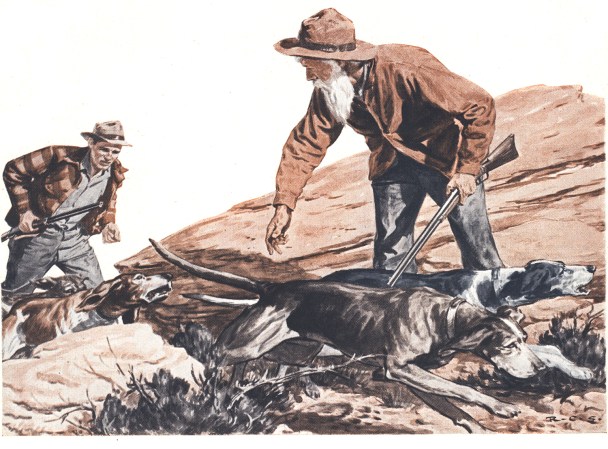

Seeing the 4-inch tracks around the attack site, Bodenchuk knew the big tom had drawn blood again. He loosed his hounds–Gomer, a bluetick, and Brutus, a redbone. The dogs’ wails echoed up the canyon’s walls, but the lion went up a cliff as though he knew the dogs couldn’t leap like he could.

Three days later the tom killed again. “He was a hit-and-run lion,” says Bodenchuk. “He was smart enough to eat from a kill just once.”

This time when the dogs started bawling, the tom beelined two miles for the precipice at Saleratus Creek. Stepping off his gray mare to see where the cat lost the hounds, Bodenchuk couldn’t make out where he’d jumped to; the tom had just launched into space as if he had wings.

Wright and Bodenchuk took five lions off the Old Woman Plateau in 1993, but they never treed the king. Wintch lost a fifth of his sheep to predation that year. The tom was earning his reputation.

TAKING EVERY ADVANTAGE

In the winter of 1993-94, Bodenchuk decided to end the slaughter. A friend had drawn a sportsman’s tag for the unit. The two hunters went in on snowmobiles. A hot sun will burn a track off bare ground by late morning, but a track in snow can reek of lion for days.

On the fourth day, after passing up smaller cats, they jumped the big tom far from the rim. He was bounding 15 feet per stride and Brutus’s voice had gone from a mournful bellow to a sharp bawl. Instead of heading for the rim at Saleratus Creek, which he could not possibly have made, the cat turned north across open country. This was going to be easy, thought Bodenchuk. But then he remembered Coal Mine Road. Trucks pound up and down that road every day but Sunday, and it wasn’t Sunday. Filled with tons of coal and plowing down the tight, icy road, coal trucks stop as slowly as trains. Gomer and Brutus could be crushed.

Bodenchuk came over a rise on his snowmobile to see a coal truck miss the big tom by inches. The driver didn’t seem to notice. Bodenchuk’s dogs were in the road behind. Another truck would be along any moment. He knew the cat would likely cross the road repeatedly. It was a risk he couldn’t take. He chased down his dogs.

THE DARK YEARS

Native American tribes have no shared myths pertaining to the mountain lion. Mountain lions, it seems, were too elusive to be classified collectively. Wintch came to hate this elusiveness. The following four years were dark and bloody for his sheep and cattle. He lost an average of 600 sheep a year from his herd of 3,000 on the plateau.

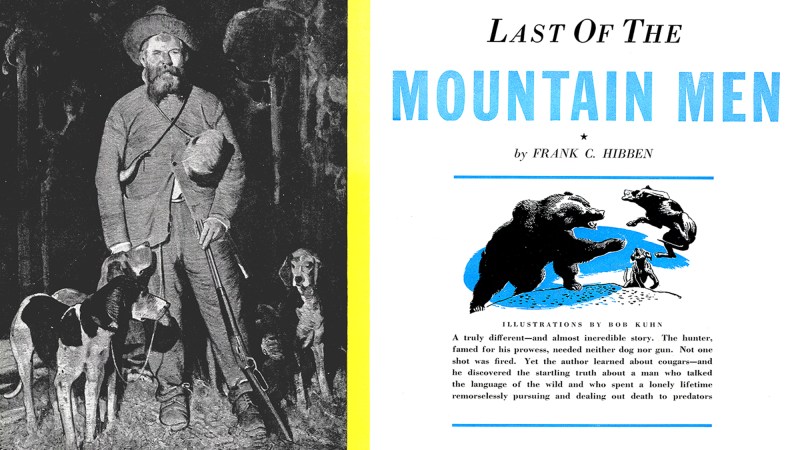

Bodenchuk’s journal entries during this period read like a Western dime novel. These were days of desperation and bravado. He chased one stock-killing female on foot up a cliff where he cornered it on a ledge under ancient Indian pictographs. He crawled into a mine shaft after another and killed that cat in total darkness by shooting at the sound of its deep snarl. He killed two lions that were living under a porch, feasting on house cats. During this time, Bodenchuk estimates that he and Wright and a few others pursued the big tom at least 200 times, but on each occasion the cat jumped off the rim into nothingness.

After all these years of loss, Wintch had to make the toughest decision of his life. The lion wars were over. He wouldn’t put sheep back up on the plateau. He says it was “like trying to hold onto a handful of sand–no matter how hard you try, it just slips through your fingers.” When he was a boy there were 29 herds of sheep in Saleratus Canyon; now there are none.

The tom should have died the following winter. In January 1995, he was living high near the rim. An elk herd was socked in there, and the tom was living off them. It was during this time, Bodenchuk believes, that an elk broke the big cat’s jaw. The tom was probably kicked with a rear hoof, says Bodenchuk. How he ate for the next six months until his bones fused is a matter of speculation. But the pain is very imaginable.

NOW IT’S PERSONAL

In 1996, Bodenchuk was promoted from regional supervisor to State Director of Wildlife Services. He moved 200 miles north to the Salt Lake City area. “Even as I pursued other lions, I kept thinking of that old tom,” he says. “I suppose, like a great athlete, a hunter is measured by the skills of his adversary. In that regard, that tom had soundly whipped me. I wanted a rematch.”

Without livestock up on the Old Woman Plateau, Bodenchuk had to draw a personal tag to hunt the big tom. To boost his odds, he talked his wife, Debby, into applying. She drew in 2000. The dominant cat was so bold that he walked right through camp one night. Wright joked that the tom wanted to see “who had been chasing him all these years.” Still, the cat made the rim that day and the wild chases and dramatics that followed broke Debby of any urge to climb in the saddle and pursue lions again. She now describes lion hunting as “foolhardy rides up Rocky Mountain inclines behind baying hounds in hopes of catching something your horse would rather not.”

Bodenchuk drew a tag in 2001. The old tom was at least 9 years old by then; at that advanced age another tom would likely kill him for his kingdom soon. Bodenchuk decided to team up once again with his old hunting companion, Kelly Joe Wright. Bodenchuk says, “One time we had to restrain Kelly physically to prevent him from tying a rope to his waist and dangling himself off a cliff in a suicidal attempt to kill a ledged lion he couldn’t climb down to. There’s no one I’d rather chase lions with.”

RACE TO THE RIM

High in Spring Canyon on the night of June 13, 2001, the big tom killed a large mule deer buck. He had either lain in wait or spotted the buck below in the canyon. In two bounds the big male jumped on the buck’s back, sank his teeth into the deer’s neck and used a forepaw to pull the buck’s head around, breaking the mule deer’s neck before they rolled together, raising dust in the darkness.

The old tom left around dawn. At this same time, down in the bottom of Spring Canyon, Bodenchuk and Wright were on horseback, following their hounds. Bodenchuk had brought Brutus and Gomer, and Wright had supplied two more: Bones, a black and tan, and Reba, a redtick. Wright’s dogs would tend to get out ahead and run a track fast. “Reba is the smart one,” says Bodenchuk. “She’ll figure out a track quickly. Bones lives to hunt. If he’s not watched closely, he’ll disappear and hunt on his own for days.”

The dogs struck the track. Seeing the fresh carcass and hearing the dog’s excitement, they knew the cat was close.

The old tom had a full stomach, which often makes chases short. Still, he moved out ahead and pulled one of his characteristic tricks: He jumped up ledges, climbing out of Spring Canyon toward Rock Canyon.

As the two men pushed their mounts up ledges onto the mesa, Bodenchuk, now nearly as well-schooled in the terrain as the old cat, pulled a trick of his own. He took a ledge from Spring Canyon into the rough country above.

He heard the dogs. Ducking and weaving as their horses struggled up through boulders and oak brush, he and Wright followed the sound to the top of Trough Hollow toward Rock Canyon.

Down the canyon they went, sliding down rock chutes. The hounds’ voices changed. Treed? No. Was the old tom scattering the dogs?

The lion left Rock Canyon by jumping and clawing up sheer sandstone. The hounds searched for a way up. Bodenchuk and Wright lost track of the chase, now three hours old.

Bodenchuk and Wright rode wildly for two hours up and down vertigo-inducing terrain. They found nothing. As they climbed higher, hoping for a voice on the wind, thunder broke. A storm blew in, fast as they can in the Rockies, and washed away their hopes.

They went back to the truck. Wet and dejected, they moved two miles to the other side of Trough Hollow. This was the fourth day in a row spent chasing the old tom. A pair of antler collectors had got in the way the day before, confusing the dogs and throwing them off a hot track.

As they came down Balsam Hollow’s sage flats, now eight hours into the endurance match, they saw the two antler collectors. They pulled up, letting the dust wash over them.

“Now ain’t you a sight!” said one of the two men.

The sun was a red ball on the horizon; they had no time for social proprieties. Bodenchuk desperately asked whether they’d seen the dogs. The collectors pointed to the rim.

Throwing dust to the lip of the rim, Bodenchuk and Wright jumped off their mounts. The hounds could be heard far below, but the horses couldn’t get down there. Stumbling down the rim, across gravel and dull red dirt that seemed poised to flow like water over 200-foot plunges, they half-slid 300 yards before they could see the dogs.

Bones and Brutus were under the cat (Reba and Gomer wouldn’t limp back for two days). Bodenchuk ran bent over, hiding his profile, for 200 yards down Saleratus Creek. The tom was 15 feet up a pine, just 100 yards from the rim. There was no time to lose. If the lion jumped, he could fly to safety in five or six bounds.

Bodenchuk was under the tree before the old tom saw him. The lion showed his teeth, growling low and mean. He gathered his legs under his body, preparing to pounce. The dogs, seeing the men, lay down, exhausted. Bodenchuk had forgotten his rifle. He had a moment of confused panic as the tremendous cat poised to leap.

“He looked down at me with his green lion eyes,” says Bodenchuk, “like he was deciding whether to fight or to flee. Then I remembered the .357 on my hip.”

The 160-pound tom jumped!

Bodenchuk drew and fired in one motion. Landing at Bodenchuk’s feet, the wounded tom took a step toward the rim that had always meant safety, but then stopped and turned. At spitting distance, the two hunters’ eyes met. The lion laid back his ears and his green eyes went dark with revenge. Bodenchuk shot again, toppling the cat over.

BACK ON THE PLATEAU

I stood with Bodenchuk on the rim overlooking Saleratus Canyon on a June afternoon. The sun painted deep shadows on the jagged landscape 1,000 feet below.

Bodenchuk said as he looked down into the canyon, “I can’t help feeling a void, now that that old tom is gone from this rim.”

I found myself thinking that Bodenchuk is a modern breed of game referee. He feels that predator populations should be managed, not destroyed wherever they’re found, as was the way until only a few decades ago. He also doesn’t put predators before people, as environmentalists so often do. It’s Bodenchuk’s job to solve problems between people and predators so that they both can coexist in the state of Utah.

Bending beneath a pine on a point, Bodenchuk looked pleased. “There’s another big tom on this rim.”

The scratch was large and around it were tracks too wide to be made by anything but a mature male.

“Probably one of his offspring,” remarked Bodenchuk. “Maybe my son would like to come and hunt him. I’d like my son’s life to become intertwined with a lion’s.”

A Dream Job

When Mike Bodenchuk saw this ad in OUTDOOR LIFE in the early 1960s he knew he didn’t want to be a fireman or a police officer. When I asked whether he made the right decision, he joked, “I’m about convinced there’s such a thing as an adventure gene…” Before he could continue, his wife deftly destroyed his dramatic pause with a sly giggle. I was happy to find that she takes his wild lifestyle lightly. A few days earlier we were sitting in the cab of a pickup hauling mules and lion dogs to the Book Cliffs. Bodenchuk and Cory Vetere, a lion specialist with Wildlife Services, passed the time by counting up the divorces the division’s 26 hunters have had. After a lot of counting fingers they decided the divorce rate for Wildlife Services hunters runs about 50 percent. Too many weeks spent camping in the high country tracking stock killers only to come home smelling like a mule take their toll. But it sounded like a dream job to me.