Ice and snow crunch under our tires as we pull up to one of the most popular stretches of river in Wyoming. On any given spring day, this spot on the North Platte is shoulder-to-shoulder combat fishing in front of a small dam that releases water year-round.

On this morning in early January, the temps won’t break freezing and the wind is blowing 25 mph. My husband and I are the only ones fishing the first public portion of the iconic Gray Reef section—the one that draws tens of thousands of anglers to its banks with the promise of 30-fish days. We lob streamers most of the morning without much action. By afternoon, we hit the symbol of fishing in Wyoming—a sign that reads private land: beyond this point fishing by permission only.

Welcome to wade-fishing in Wyoming. Our neighbor to the north, however, doesn’t have those signs—not legal ones anyway. Nearly every stream in Montana, whether on public or private land, is open to wade-fishing up to the high-water mark via public access. Every stream in Wyoming on private land is closed to wade-fishing without the aforementioned permission.

Montanans say their water laws boost the economy and make anglers happy, bringing them back day after day. Wyoming says its private stretches feed a growing economy that’s able to offer exclusive fishing while also keeping the hordes from over-pressuring the resource.

At its core, the issue is as old as the American West itself: Who gets access to its natural resources? For anglers, what matters most is what the rules mean on the water. Can we walk the bank or not? Can we fish around that bend? Can we drop anchor and cast?

Water-access battles continue to light up like prairie fires around the country (see the sidebar at the bottom of this story), but the two states that have held fast to their laws are Wyoming and Montana. So which state has it right?

Montana: Welcome to Big-Access Country

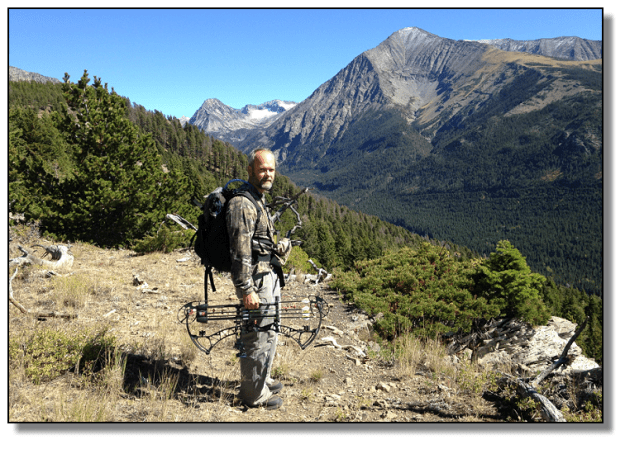

Ray Pearson and I shimmy between the guardrail on a county bridge and a fence with a no trespassing sign, then slide down the embankment to the Boulder River.

A pocket under the bridge always holds fish, he says. We’ll catch something there.

The spot embodies just how unique—and controversial—Montana’s water laws are. Land surrounding that county bridge is private (hence, the no trespassing sign). But if a government bridge crosses water, anglers can access the river from both sides within the easement, which is government land used for bridge maintenance.

I cast a few times, swinging nymphs under the clear water, and feel a strike. I reel in a mountain whitefish, a native species that more closely resembles a tropical bonefish than the ubiquitous trout. Another one eats not long after.

Pearson watches, more content to see me catch fish than to cast himself. At 66, white hair peeking from under his baseball cap, he’s landed plenty of fish on the Boulder. He’s reaping the benefits of years of work fighting for access like this. The New Jersey transplant moved to Montana in 1971 and never looked back.

The Boulder River shows why anglers consider Montana’s access laws to be the gold standard. It rushes out from the Beartooth Mountains on national forest land and then immediately flows through private ranches and vacation properties. Michael Keaton, Tom Brokaw, and Brooke Shields have all owned property along its banks. Almost none of the lower river runs through public land in the roughly 30 miles between the forest boundary and the city park in Big Timber (population 1,674).

Plop this river in Wyoming, and no one without permission or a hefty checkbook would get to fish along its banks. But because it’s in Montana, an enterprising angler could walk and fish the entire slippery, windy, boulder-filled stream as long as he or she stays below the high-water mark (in Montana that’s defined as the line where vegetation changes dramatically because of frequent water).

Montana’s access laws didn’t come about by accident. In 1972, a major overhaul of the state constitution stated that “all surface, underground, flood, and atmospheric waters within the boundaries of the state are the property of the state for the use of its people.” What followed was a series of challenges trying to block access for wade-fishermen.

Most of those assaults were fought back by a ragtag group of local Montanans called the Public Land/Water Access Association (Pearson is the association’s treasurer). It formed in 1986, and operates on little more than $20 donations from members. Even with about 1,200 members and a state supreme court ruling, the group continues to beat back access threats as if in a never-ending game of policy whack-a-mole.

Other groups have joined the fight more recently—Backcountry Hunters & Anglers came out swinging in states like New Mexico and Colorado. If a formal threat hit Montana, “It would be priority number one,” says Rob Parkins, the group’s public waters access coordinator. The New Mexico Wildlife Federation is also involved in growing water-access issues in its state.

Trout Unlimited, the country’s most prominent cold-water fisheries organization, worked with the Public Land/Water Access Association in Montana in the recent fight to maintain water access from public bridges.

But the group chooses its battles, says Trout Unlimited president and CEO Chris Wood. A TU committee analyzes each threat to access that’s brought to the organization.

“And I don’t think that we’ve ever chosen not to engage when asked to engage,” he says. “It’s not a full-throated ‘access for everyone.’ We have the wealthy donors who like private access, and rank-and-file members who want more access. It’s not an easy issue to solve.”

When Pearson and I are done fishing the Boulder, we retreat to the Timber Bar in a small ranching and mining town west of Billings, where outfitters, ranchers, environmentalists, and miners fill the room, drinking and talking. A couple of guys play pool in the back corner. Antlers hang on the wall. With a college football game playing on the TV and beers flowing, I get to see why “access for everyone” isn’t always an easy issue for TU. Local outfitter Mike Colpo requires little prodding to sum up his opinion of Montana’s access laws: “It’s all horseshit.

“Those people want everything. They want all the access, and then when they can’t walk up the boulders, they want to come up on our land and trespass,” he says. “This whole access issue needs to be rethought. Private-property rights should be respected.”

There’s plenty of bad behavior by private landowners as well. Pearson was once shot at by a truck full of teenagers while fishing a stretch of water surrounded by private land. They peppered a bluff above him with .22s.

Brian Grossenbacher, a fishing guide-turned-professional photographer who joined us on the Boulder River, has a similar story. He met a friend on a river in central Montana that was surrounded by private land. They paid a landowner $50 to launch from his property. Two hours later, they pulled off on the bank in their raft to eat lunch and a guy came by in a truck and started screaming obscenities at them. Grossenbacher and his buddy didn’t respond. After floating another 20 minutes, they heard gunfire.

“You can tell when the shots are going over your head. You can feel the brush of air, and the sound is very different,” Grossenbacher says. “We hunker down in the bottom of the raft, and my buddy is laughing. He said, ‘If I told you I’d been shot at, I knew you wouldn’t come. This happens every time.’ ”

These are extreme examples, of course, but they show the downside of unlimited access. There’s more opportunity for tension between anglers and private landowners, stories of landowners harassing river users and anglers trespassing. And yet most trout anglers would argue that the access is worth the controversy. Later in the night, I meet Patti McGowan and her husband, Ed. She’s a nurse; he’s a platinum and palladium mine manager. They say they won’t leave Montana because the fishing laws are so good.

“We don’t think about access,” Patti says. “We just fish.”

Wyoming: Pay to Play, or Fight the Crowds

As much as someone can own a river, the North Platte feels like mine. It’s a lazy stream with about 3,600 fish per mile that meanders through sagebrush flats and alfalfa fields, then tumbles through a series of dams.

It’s where I caught my first brown trout. It’s where I first stood, hip-deep in a pair of waders (boys’ size large because the local sports store didn’t carry women’s), and ineptly smacked the water with a Woolly Bugger. It’s where we first took our daughter fishing, strapped to my husband’s chest, six months after she was born.

Though it’s always been the same to me, the North Platte bears little resemblance to its historic form. Accounts from the 1800s say the river swelled to almost a quarter-mile wide through my hometown of Casper, before trickling down to almost nothing in the fall. Native fish included sauger, shovelnose sturgeon, and channel catfish. A blue-ribbon trout fishery it was not.

But one dam went up and then another. Contracts were signed, agencies negotiated on management plans, fish were stocked, and, 100 years later, the North Platte River from Gray Reef Reservoir past Casper is now known as one of the best trout fisheries in a state known for trout fishing.

We’ve spent enough time on this river that we know where we’ll catch fish and where we won’t. We know the time of year we can cross and when we can’t. We know exactly where the public portions end. And you should too if you want to come fish here.

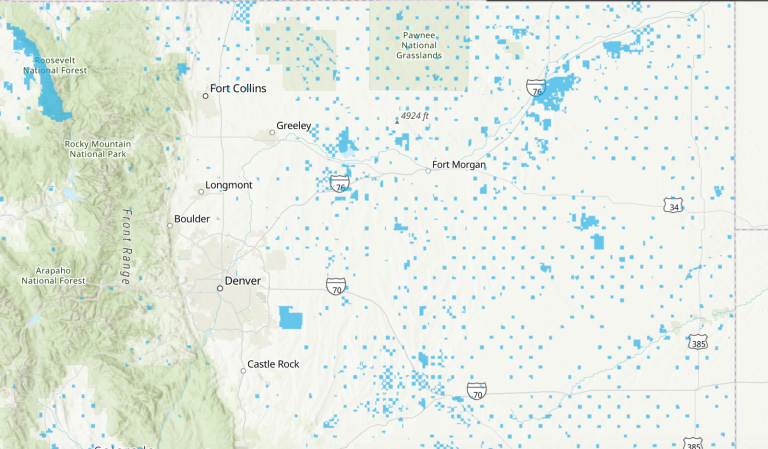

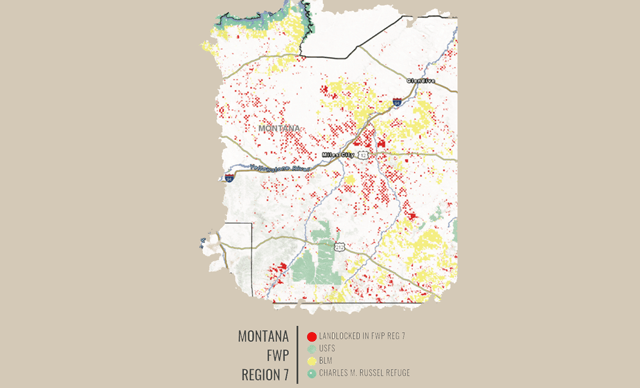

Open up a map of Wyoming, and you’ll see why anglers either learn the public stretches or take home a $420 trespassing ticket. Blue lines snake across much of the mountains and plains. They’re the arteries of the West, carrying the nation’s lifeblood from mountains to lowlands. Look closer at the map, and you’ll see that as most of those rivers dump out of their high-country origins, they’re surrounded by white—a paintbrush stroke covering both sides. White equals private. No trespassing. No anchoring to fish. No getting out of the boat to pee.

For a stretch of river in Wyoming not flowing through national forest, access on the Platte is actually pretty good, says Matt Hahn, Game and Fish’s fisheries supervisor in the region. The blue-ribbon stretch near Casper is close to 90 miles. About 25 of those are public. Some are grateful—that’s 25 miles of public access. Others wonder why the hell 65 miles of river is off-limits to wading or anchoring.

It wasn’t always this way. Wyoming and Montana were similar after an 1876 court decision stated land up to the high-water mark of navigable rivers belongs to the public. But then, in 1958, an angler took a landowner to court requesting a judgment on his right to wade through private property on the upper stretches of the North Platte.

That case eventually went to the Wyoming Supreme Court, with the court ruling largely in favor of the landowner, saying a river had to be navigable for interstate commerce year-round in order to be public for wading. The water itself was a public resource, and anglers were free to float and drag their boats over shallow sections (so landowners can’t put up fences), but the ground is private (so anglers can’t cast a line while dragging their boats).

And there the ruling stayed. Any change would need to come from lawmakers or a lawsuit designed to reach the U.S. Supreme Court. Neither is likely in Wyoming, says Tom Annear, a retired water management supervisor for Wyoming Game and Fish.

“Landowners have the incredible privilege of owning the bed of a navigable river. Why would anyone support changing that? If I owned a chunk of the North Platte, I don’t think I would support changing it,” he says.

For private landowners here, the law is simply the law. Blake Jackson, co-owner of the Ugly Bug Fly Shop and Crazy Rainbow Outfitters in Casper, has fished and guided in Montana and Wyoming. He leases 8.5 riffle-filled miles of the Platte, and he knows why it’s frustrating to the public. But he also argues the benefits to the fishery plus state and local economies.

“There’s commercial gain. It allows us to have private put-ins and take-outs. I also think there’s a big plus from a conservation standpoint,” he says. “The riparian zones and ecology of the river aren’t impacted the same [as if it were public].”

Clients choose the Platte and Jackson’s business over a river like the Bighorn in Montana because they know they’ll have stretches with no wade-fishermen.

Even then, Jackson figures he catches a couple hundred anglers a year trespassing. Some don’t know the law because they came from states like Montana or Idaho. Many know exactly what they’re doing and trespass anyway. He gets sick of the trash he says they leave behind and the literal crap on the banks.

“We often get people saying we shouldn’t enforce the law,” he says. “If you’re the one who owns the property, would you allow people to litter on it? We get people trespassing, and we will explain the law. They will scream and yell at us, and say it’s wrong and it’s not their belief, and that’s fine, but it is the law. They are actively breaking the law on purpose at that point.”

So, he calls the sheriff.

The laws around river access might be clear, but the private economy claims are muddy when you look more closely at the numbers. A recent report from the American Sportfishing Association showed that in 2016, 374,770 anglers spent $494 million in Montana, while 322,032 anglers spent $594 million in Wyoming (these figures count dollars spent in retail sales in each state).

By contrast, the Bureau of Economic Analysis said the overall “value” of boating and fishing in Montana in 2017 was almost $135 million while Wyoming’s was just under $40 million.

None of these reports detail the differences in population between the states or number of river miles per state. So, do private river laws actually improve recreation economy? It all depends on who you ask.

Home Waters

As the sun reaches the horizon on the Platte, I cast a few more times on a side channel and finally feel a tug, almost like my fly clipped moss on a rock. I set the hook, and a hefty rainbow races downstream. I carefully fight the fish to hand, trying hard not to lose my only trout of the day.

I release the rainbow just feet from where I caught some of my first fish in this river, where I learned the value of a San Juan worm, and where I came to appreciate fishing for more than just catching. It’s the same place that is overrun with anglers in the spring and summer. But Wyoming is home, so we’ll fish early and late, when we’ll find fewer crowds. We also accept that there’s some water we’ll never get to access.

There’s one 40-mile stretch of river near my home that isn’t deep enough to float and is mostly surrounded by private land. Hahn, the Casper biologist, electro-fished it once years ago and saw hundreds of fat, healthy 16- to 20-inch brown trout. Those fish will always be off-limits. We can only dream about what it would be like to walk that 40-mile stretch of freestone river and fish like kings.

Read Next: The Crazy Story Behind the Water Access Battle in New Mexico

Public Water Wars Being Waged Right Now

These are public water access battles that are going down around the country…

Louisiana: The Louisiana constitution, as interpreted by some courts, says tidally influenced or navigable water is public, meaning coastal land is public. Now, as that same land erodes, sea levels rise, and canals break down, the line between what is public and what is private is being hotly contested. Mineral rights beneath the water are at the root of the debate, but anglers are collateral damage.

New Mexico: In 2014, New Mexico’s attorney general issued a nonbinding opinion based on the state’s constitution, saying anglers can legally wade and fish to the high-water mark. The next year, legislators signed a law barring anglers from wading to the high-water mark on “non-navigable public water.” This led to a flurry of requests from landowners to certify the rivers flowing through their property as non-navigable, placing no trespassing signs on banks and even fences across streams. In 2019, the state’s new Game and Fish Commission began a review of the new regulations, but this year, the commission chair, who supported public-water access, was not reappointed by the governor. Read the full story here.

Colorado: Instead of deciding what is and isn’t navigable, Colorado just, well, hasn’t. That means whether or not a river can be fished by boat is up to landowners—sort of. An early ’80s law says an angler can’t touch the banks of a non-navigable river, but whether or not you can float, and what rivers are and aren’t navigable, is still up to interpretation. After being threatened and assaulted with rocks by a landowner, one angler is suing Colorado to force a legal opinion on at least one stretch of river.

Indiana: In late 2019, lawmakers proposed a bill to give property owners the right to their portions of the shoreline of Lake Michigan, despite a state Supreme Court ruling in 2018 declaring that Indiana’s 45 miles of shoreline are public up to the high-water mark.