We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

By the time I registered the rooster that had flushed into the air directly above me, the prairie wind had sucked him up and away. I managed to pepper his slipstream before he rode the 30-mph gust over a hill of beans to safety.

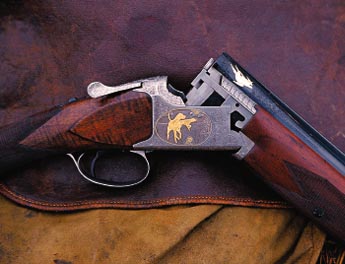

I could’ve blamed the wind (which I did, a little), but otherwise the fault rested squarely with my poor shooting. It certainly didn’t lie with my shotgun, a circa-1953 Browning A5 Sweet 16 with a fixed modified choke. This was admittedly my first time shooting the A5, but it already felt familiar. The shotgun was an unexpected gift from an elderly neighbor, who couldn’t keep it when he moved to an assisted-living home last year.

Apart from the itch to hunt with such an iconic gun, it also happens to be the only one I own that would accommodate the new 16- and 28-gauge Prairie Storm loads I was outside Aberdeen, South Dakota, to test. The fan-favorite loads have been available in 12 and 20 for years, but Federal Premium introduced the additional sub-gauge loads in 2020. It’s an introduction, they note, that’s directly resulted from customer demand.

So, who are these sub-gauge customers? And is it worth swapping out your 12-gauge for a sub-gauge?

A Sub-Gauge Primer

Let’s go back to basics for a minute. What is a sub-gauge, exactly? Like most things, if you consult the masses, you’ll discover many folks can’t agree on this. Poking around some online forums revealed many hunters seem to exclude the 20-gauge from the category simply, it seems, because it’s more common. But by most competition rules and the confirmation of Field & Stream shotguns editor Phil Bourjaily (which is good enough for me), a sub-gauge is anything smaller than a 12-gauge. This includes the 16-, 20-, and 28-gauge, as well as the .410 (and yes, more obscure gauges like the 24 or the 32).

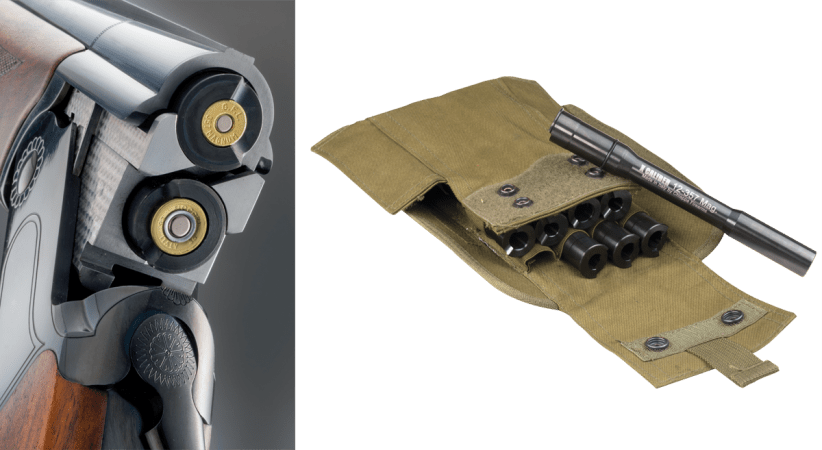

“The love of sub-gauges is very American,” says Bourjaily, pointing out that we’re the only shooters who shoot skeet in four gauges. “No other countries like sub-gauges the way we do. I don’t know why that is. I’ve read that maybe it’s because our guns were more robust and to make a lighter gun, you need a smaller gauge. And certainly, if you look at a lot of English and Continental doubles, [that theory fits]. My J.P. Sauer 12-gauge is about 6.5 pounds—it weighs what most people’s 20 gauges do. But sub-gauges have always been popular.”

So, if sub-gauges have always been popular, why the current uptick in interest and visibility?

“I always just assumed age was driving it. As hunters get older, they get fatter and weaker, and like lighter guns,” says Bourjaily. “But it doesn’t explain why a lot of younger hunters are picking them, too. There has been a lot of growth and emphasis on smaller-gauge guns. The cynical way to look at is to say, all the gun companies can do is sell more guns to the same people.”

Ammo Trends

But there is, of course, plenty of genuine consumer demand for sub-gauge guns. The Benelli 828 U in 20-gauge, new for 2020, is just one example of rolling out sub-gauge offerings in a popular, well-established 12-gauge. There’s one gun in particular that many folks have pointed to as helping renew interest in sub-gauges, and that was the release of the modern Browning A5 Sweet Sixteen. And as interest in sub-gauge shotguns have swelled, ammo manufactures have been delivering.

“Sub-gauge loads have historically been a little harder to find in the typical sizes you want for whatever game you’re chasing—pheasants or grouse or ducks,” says Jared Wiklund, public relations manager for Pheasants Forever and one of my companions on the South Dakota hunt. “But the technology is so good nowadays that people using sub-gauge shells, I think it’s going to be a thing of the future.”

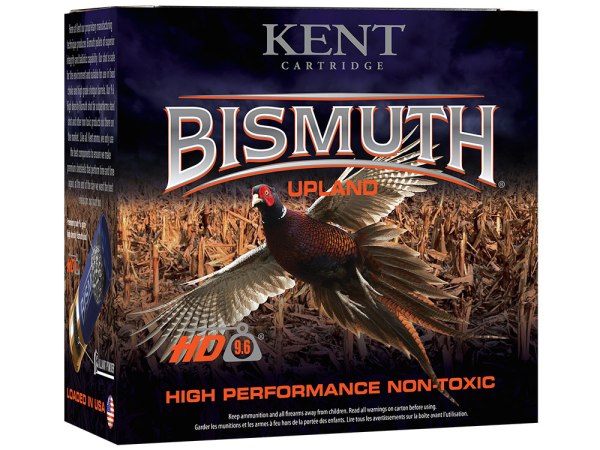

Bismuth has been making a comeback among wingshooters and, unless you’ve been living under a very large rock, you know that some of that technology has been a game-changer for turkey hunters. Tungsten Super Shot has swept the turkey-hunting world, making an impact on hunters with both its performance and its price. TSS is twice as dense as lead, which leads to increased energy and lethality down range.

Turkey hunting also happens to be the one category where manufactures are really seeing prominent sub-gauge growth. At Federal Premium, 20-gauge and .410 ammunition make up nearly half of turkey sales. Of the entire shotshell category, however, 12-gauge is still king.

“We typically sell 80 percent 12-gauge, 15 percent 20-gauge, and the other 5 percent makes up all the rest,” says Dan Compton, product line manager for Federal Premium. “The 16-gauge ammo has seen a steady increase in demand over the last eight years. This is mainly due to increased offerings from gun companies in lightweight upland guns. Prior to that, the 28-gauge saw a surge in popularity.”

Read next: 5 Custom Shotshells That Are Better Than Steel

In recent years, Prairie Storm lead loads in 16- and 28-gauge have been the top-requested shotshell product from customers. The only place Federal currently offers TSS in 16- and 28-gauge loads are through its Custom Shop. This is because TSS is still a relatively niche and expensive product, despite all the buzz.

Banning 12 Gauges?

When Holly Heyser started hunting 14 years ago, she bought a 20-gauge Beretta 391 because that’s what the hunters she knew told her to buy.

“And I liked it, but when I ended up getting a 12-gauge a few years later, I ended up killing a lot more ducks,” says Heyser, acknowledging that she also started practicing more when she got the larger gauge. “So for a while, I really kind of resented the whole 20-gauge thing because I’ve been told I needed it because I’m a girl. And I’m 5-foot-8. I’m not delicate.”

As the communications director of California Waterfowl, Heyser gets plenty of invites to hunt private duck clubs across the state. Before attending one such hunt, she learned that members and their guests weren’t permitted to shoot a 12-gauge. According to Heyser, this gauge restriction isn’t the norm among California’s hundreds of duck clubs, but it is becoming more common.

“When I first heard about this trend, I thought it was kind of snobby. Like, we’re going to use our small-bore guns,” she says, impersonating the kind of pretentious, older hunter who almost certainly wears tweed. “It just reeked of elitism to me.”

She arrived to hunt, comfortable with her 20-gauge but curious why it was required. Club members told her the “No 12-gauge” rule was designed to reduce bird disturbance.

“I thought that was the silliest damn thing I’ve ever heard in my life. Because it’s a gun, and it’s not like birds go, Oh, just a 20-gauge. I’m going to keep flying through.”

She remained skeptical until a hunt with Paul Bonderson of Bird Haven Ranch, who had just implemented his own ban on anything larger than a 20-gauge. Because she was introducing a group of wildlife biology undergrads to hunting (“so they get to know their constituents”), Heyser wasn’t shooting much that morning. And when she wasn’t shooting, she noticed surviving ducks were recovering from volleys more quickly than she was used to.

“When you fire your gun, it’s like this whole explosion that clears out everything. It makes everything shut up, it makes everything fly away. And when it’s a 20-gauge, everything just goes back to normal a little bit faster. That’s when I realized it wasn’t B.S., and it wasn’t something snotty. It was a legitimate claim.”

The Case for Switching

In addition to quieter shots (most of the time), both for birds and everyone in the blind (including your dog), sub-gauge shooters have to deal with less recoil—usually.

“People assume that a small-gauge gun is going to kick less, and it doesn’t always,” says Bourjaily. “Coaching trap, we get kids who’re still shooting their first guns, like their little Mossberg 500 youth gun. Those’ll kick the snot out of you.”

Recoil has nothing to do with the gauge of a gun, but rather the weight of the gun and the kind of load you’re putting through it. But with the right combo, hunters can enjoy reduced recoil—and the improved opportunity for follow-up shots that it affords. Tony Vandemore of Habitat Flats says he hasn’t killed a duck with a 12-gauge in a long time.

“With today’s chokes and loads, I don’t think you’re under-gunned one bit with a 20-gauge,” says Vandemore, who initially got his 20-gauge, a Benelli M2, to make long days in the turkey woods a little easier. Then he started shooting teal with it, and didn’t pick up his 12-gauge once that fall. That was a decade ago. Now, he only uses his 12-gauge for snow geese.

Vandemore doesn’t feel guilty throwing the synthetic M2 in the bottom of his blind or hunting in nasty weather, but he saves his favorite duck gun, a beautiful 28-gauge Benelli ETHOS, for the sunny days.

“Thirty-five yards on late-season mallards with the 28-gauge are no problem as long as you pattern your gun, you know your choke, and you know the loads you’re shooting,” he says. “More than anything, I think we all kind of go through phases. When I was young, I needed big, bigger, biggest. I mean, 3½-inch 12-gauges—just let it rip. Man, it just got to where my head would hurt. The older you get, the more it’s about how close you get them, rather than how far away you can shoot. Anything I’m going to call the shot on for ducks is going to be well within range of a 28-gauge, let alone a 12-gauge.”

Over the years, Vandemore has noticed a lot more hunters arriving at Habitat Flats with 20 gauges in tow. He’s also getting a lot more questions from folks who are curious about how to get started, and what kind of set up he runs. In both of his 20- and 28-gauge Benellis, Vandemore has a Rob Roberts T3 choke and shoots tungsten-based Hevi-X No. 6s. For big honkers, he’ll use 4s or 2s.

Besides all the concrete benefits associated with shooting a sub-gauge, there’s appeal for some hunters in the street cred and bragging rights associated with shooting something perceived as more challenging, and a little different. That’s not why Vandemore hunts with sub-gauges, but he is aware of the phenomenon.

“The biggest satisfaction to me is getting them in close, but killing them with a 28-gauge is also satisfying,” Vandemore says. “So many people think it isn’t a wise choice. But if you put it on paper, it’s an extremely lethal load with good pattern density. You’re not doing anything that would be viewed as unethical, in my opinion.”

Ethical shooting is actually another bonus Heyser has heard about at those California duck clubs that ban 12-gauge use.

“That’s based on the erroneous belief that a 20-gauge doesn’t have the range of a 12,” says Heyser, noting that a shotgun’s range depends entirely on the load and choke. “Even though it’s wrong to think that the 20-gauge can’t shoot as far as the 12, it does have the psychological effect of causing people to take closer shots. Which makes them more successful—and reduces the really annoying phenomenon of sky busting.”

The (Weaker) Case Against Switching

The case for down-sizing your bird gun might seem iron-clad, but it’s not a panacea for everything that ails your wingshooting, or your wallet.

“If your shooting is so poor that you need those extra pellets to hit a duck—which I did, early on in my shooting career—it’s really helpful to have that,” Heyser says. “But if you know what you’re doing and you know how to lead a bird, a 20-gauge is going to kill them just fine.”

Ammo availability has historically been a hitch for sub-gauge shooters, and sub-gauge duck loads can still be difficult to find and expensive once you do. This is particularly true for California waterfowlers like Heyser, who have to navigate more complex regulations when purchasing ammo. She makes sure to buy her ammo early, before it gets cleaned off the shelves as the season wears on.

But with recent ammo introductions and increased custom-load possibilities, pricey though they may be, such concerns are receding. These days, the main hurdle for hunters who want to add a sub-gauge to their collection is just that: ponying up for a new gun that we don’t exactly need, but definitely want.

As for my pheasant hunt, I eventually got my act together and dropped a crossing rooster with my new old shotgun. As I watched local hunters stone roosters through gale-force winds at 50 yards with smaller gauges than my Sweet 16, my take away was the same as it always is on my first rusty, and mildly embarrassing, hunts of the year: It matters very little what you’re shooting, and it matters much more how you’re shooting.