One of the most elusive creatures to roam Yellowstone National Park has been caught on a trail camera for the first time. A wild wolverine was captured bolting through the forest, the first on-camera sighting since the park began to use wildlife cameras in 2014.

Biologists estimate that there are as few as 300 wolverines left in the lower 48, so the chances of spotting this critter are pretty low. The remote trail camera, located outside of the Mammoth Hot Springs area, was originally mounted to observe cougars.

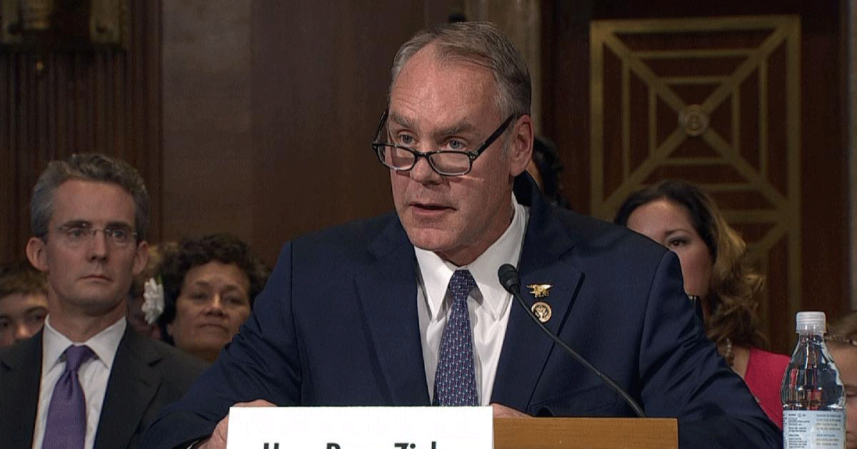

“We put out remote cameras across the northern part of Yellowstone as part of a cougar study,” says Dan Stahler, a wildlife biologist at Yellowstone National Park. “When I first saw the video, just a week after we set up that camera, it gave me goosebumps because…I’ve never seen one in person in my 25 years here.”

The video, which was posted to Yellowstone’s Facebook page last month, shows the animal scurrying through a snow-blanketed, forested area on the morning of Dec. 4.

Wolverines live in extremely low densities and have an average home range of about 500-square miles for an adult male. They travel incredibly large distances, meaning that no one wolverine lives exclusively within the Yellowstone National Park boundaries. Biologists estimate that half a dozen individuals are likely “periodically using Yellowstone.”

A study conducted by Yellowstone National Park from 2005 to 2009 documented only seven wolverines within the park boundaries. The evasive creatures are one of the most understudied mammals due to their large home ranges and low numbers in the United States. Only in the last couple of decades have biologists developed the tools and methods to monitor them.

“We know that Wolverines were once widely distributed throughout the circumpolar north, including a lot of the parts of the Rocky Mountain West,” Stahler says. “They experienced pretty substantial population declines by the 1930s, largely due to commercial trapping and predator control efforts that sought to poison everything from wolves, bears, cougars, and wolverines.”

Even though more wolverines are being spotted these days, biologists are reluctant to cite a population increase. An enormous lack of tracking and research on the species in the past century created a knowledge gap about the animals. Parks like Yellowstone are spotting more wolverines, but this is likely because technology has increased, or simply that more people are searching for them, says Rebecca Watters, executive director of the Wolverine Foundation.

“There are a lot of claims out there and counterclaims in popular press articles about what the population might be doing,” Watters says. “I think that those are generally the result of just looking at one particular area and saying, ‘Oh, well, a wolverine showed up here, and it wasn’t here before, so therefore the population is increasing.’ That’s not the way that the wolverine life history works.”

Last year, the USFWS declined to grant wolverines Endangered Species Act protections because “analysis show that wolverine populations in the American Northwest remain stable, and individuals are moving across the Canadian border in both directions and returning to former territories.”

To promote the conservation and education of the animals, Watters encourages hunters and other outdoors-people to report wolverine or track sightings with clear photos to multiple angles. With their expertise in animal tracks and voyages into the backcountry, hunters are critical to the conservation of wolverines.

“I think wolverines probably benefit from gut piles. Hunters are probably symbiotic with wolverines in that respect. We are definitely interested in hearing any hunters reports of wolverines,” Watters says.