The sign that welcomes you to Chance Black’s hometown reads, “Welcome to Greenfield, where you don’t get lost in the shuffle.”

But no matter where he went, Black wasn’t at risk of that. He knew how to make an entrance. Whenever he dropped in to see his parents at the farmhouse where he grew up, Chance would crash through the front door, hollering and banging on the walls, the couch, and whoever happened to be sitting on it.

“He had to make his presence known,” says his older brother, Cody Black. “He was always the center of attention, or tried to be. I know that’s a cliche thing to say, but he was the loud one in the group. He was going to make sure everybody had a good time. And I heard so many stories of people saying that you could be in a crowd of a hundred people, but he was going to make you feel like you were the only one there.”

Cody was in Memphis, where he attends law school, when he heard news that there had been a shooting on Reelfoot Lake. It wasn’t until a few more frantic calls that he learned his 26-year-old brother had been one of the victims. Later, he would hear that Chance had done everything he could for his friend Zack Grooms, who was also killed on Jan. 25.

“That does make me proud to know that he wasn’t—even in those final moments, he wasn’t worried about himself. He was trying to help Zack as much as he could,” says Cody. “You don’t know how you would react to a situation like that, but he was selfless in his last minutes. That’s something I’ll hang on to.”

Happy Camper

Though Chance and Cody had grown close over the last few years, like many brothers, they didn’t always get along when they were growing up.

“They’re different as daylight and dark,” says Mark Black of his two sons. “Cody always loved to read and study, and Chance was more like me. He was hands-on. You could tell him all day, but if he could watch you do something? He just picked it up natural.”

When Chance was little, he often watched his dad shoe horses. It’s work that requires several tools and plenty of patience. After seeing this process a few times, 4-year-old Chance—pacifier still in his mouth—posted up by the toolbox, always anticipating which tool was required without being asked.

“I never had to put that horse’s foot down for anything,” says Mark. “When I used one tool, I would lay it down and he would hand me the one I needed next.”

Chance was always underfoot, trying to see what his dad was doing, and he loved talking to people. Sometimes too much, as Mark often had to remind his younger son not to speak to strangers. As Chance got older, do-it-yourself work remained second-nature to him, like wiring a light switch or a car stereo. His dad thought he should become an electrician, but Chance was more interested in the Air Force (he was denied on medical grounds, for hearing loss of high-pitched noises) and later law enforcement. His hobbies were mechanical, too, like collecting guns and riding motorcycles.

“When he bought his first [bike], I had to ride it home because he had never ridden one that big. And that gave me a little bit of concern. But just like everything else, he picked up motorcycles like a duck to water,” Mark says with a laugh, before adding reflexively, “He never had a wreck, knock on wood.”

Mark Black is the chief deputy sheriff of Weakley County, a horseman, and a hunter safety and former conceal carry instructor. Chance learned to love horses and hunting, too. He started with squirrels and mainly deer hunted with his family as he got older. Then he discovered the perfect pursuit for an extravert: duck hunting. He wasn’t a hardcore waterfowler, but he hunted a few blinds on Reelfoot Lake each season with different groups of buddies.

“He loved the outdoors and being outside,” says Mark. “That was just Chance. He was not a fancy, frilly guy—plain was good with him. Material things wasn’t him. He didn’t have to have everything everybody else did. His friends were his biggest thing.”

Reed Wright, one of Chance’s closest buddies, remembers a beach trip they took with mostly couples. Chance refused to put on sunscreen and seared his skin like a steak, then asked for a photo with his “girlfriend,” stretching his arm around a patch of thin air. Saved on Wright’s phone is a video of Chance in the duck blind, performing a magic trick between flights. He promises to turn a piece of straw into a bird and covers his hand. Wearing his signature sidelong expression, Chance fusses with the straw like a magician over a handkerchief before unveiling his middle finger.

“He was just a goofball,” says Wright with a grin.

Chance lived by himself in a rental house in Greenfield, five miles from his parents. He saw his dad at least once a week and they talked frequently, often about guns that came through Final Flight Outfitters, where Chance worked as one of the gun department managers. He texted or talked to his mom every day. He liked to grill out and cook a big breakfast in the duck blind. He drank Michelob and Maker’s Mark, which his brother and friends have taken to drinking, too. But most of all, Chance just loved people.

A Friend to Everyone

Pilgrim’s Rest Cemetery is a 20-minute drive from Greenfield proper. It’s a small graveyard with a view of the rolling fields and thick woods where the Black brothers grew up. It’s a quiet spot, but there are a few people chatting at the entrance when Cody arrives in his truck. One of them spots him through the windshield and waves, smiling and tilting her head sympathetically.

“I don’t know her, but she knows me,” says Cody with a short laugh, raising his hand in reply. He drives on, then stops beside a grave in the Black family plot. It’s a raw mound of red earth, still without a headstone.

A little over a month earlier, the cemetery had been packed with mourners, and a line of cars snaked down the road as law enforcement and TWRA helped direct traffic. Chance’s service, the funeral director told his family, had the largest attendance he’d seen in his life. Even he had known Chance, if only in passing: The youngest Black would always honk and wave at the funeral director as he rode by on his motorcycle.

“I had no idea until the funeral that Chance knew that many people. I mean, good gracious,” says Mark. “And we are extremely proud of that, that Chance touched that many people.”

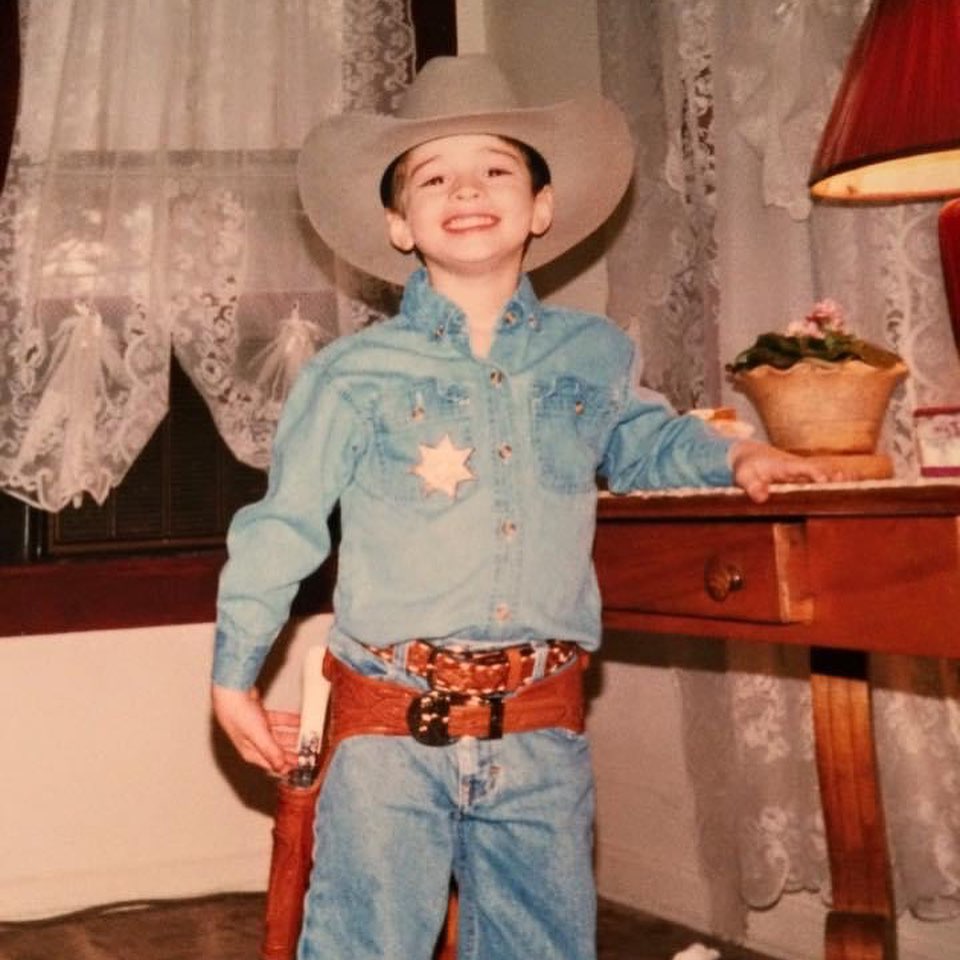

The funeral fell on Jan. 31, 2021, the last day of Tennessee’s duck season. Chance was buried in a Sitka button up he’d received for Christmas, a pair of Wranglers, and a 1994 Western-style belt buckle he had swiped from his dad to wear on nights out. He liked to tell strangers he’d won it himself at the rodeo, many of them not getting the joke that Black had been born the same year. In an exchange of sorts, Mark Black now wears the Glock 42 his son always carried on his own hip.

“What hurts the most is just him being gone,” says Cody, who had pictured Chance as an uncle, maybe, to the children he might have some day. But definitely they would share responsibility for the family farm and hunting land, just as their own dad and uncle do.

“I’ve always had in my mind that me and Chance were going to do that. And [since] he was more of the outdoorsy hands-on one, I had always counted on him being there for that. I think that’s what I miss the most, knowing that there’s not going to be any kind of future with him.”

Like many others who heard what happened on Reelfoot, the Black family was worried about how it would affect duck hunters—particularly those who knew Chance and Zack.

“We knew it was something [his friends] all loved doing, and we didn’t want them to not want to go anymore,” says Cody. “It’s not what Chance would have wanted. He would’ve wanted them to keep going and have a good time. We don’t want [the shootings] to take away from anybody’s enjoyment, whether it be theirs or anybody who saw the story.”

The Blacks do hope the world remembers Chance, “who had a heart as big as the outdoors,” for his kindness. Chance rooted for the underdog and made it a point to talk to people standing alone at parties or events. On Thursdays, his one day off of work each week, he would drive out to his grandmother’s house and mow her lawn.

“I don’t think he saw any bad in anybody,” says Mark. “Everyone was a friend to him.”

On the day of Chance’s funeral, Final Flight Outfitters closed shop and gave its employees the day off to attend the service. In the weeks that followed, business returned to normal, and employees adjusted to Chance’s absence behind the gun counter.

Beside the register in the shop is a framed photo of their former coworker, taking in a view of Reelfoot from the duck blind. The photograph is arranged so it faces the entrance to the store, to greet every customer who walks in the door.