One of the most divisive players on the Colorado ballot wasn’t the presidency or a contentious senate race, but the gray wolf. While Joe Biden and newly elected senator John Hickenlooper decisively won Colorado with a nearly 10-point margins, a 50.8 percent to 49.1 percent split concerning the restoration of gray wolves divided the state.

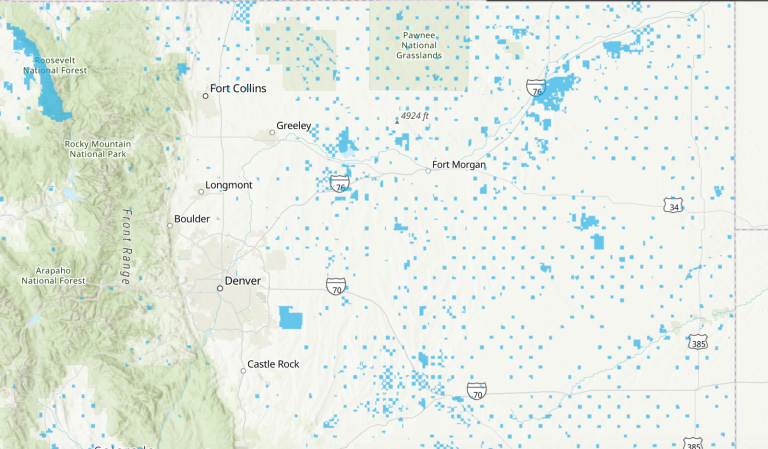

Voters narrowly approved a ballot initiative to reintroduce gray wolves west of the continental divide. Proposition 114 requires Colorado officials to restore and manage the population by the end of 2023. The animal’s historic range spans across most of North America including Colorado, where the native population was hunted to extinction by the 1940s.

Ballot Box Biology

This marks the first time a state has voted to reintroduce an animal into its ecosystem. Opponents of the measure question the wisdom of allowing wildlife management practices to be determined at the ballot box.

“Ballot box biology is reckless. In this particular case, it totally undermines the authority of Colorado’s wildlife professionals who have said time and time again over several decades that a forced wolf introduction is a bad idea,” said Kyle Weaver, Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation president and CEO in a press release.

Wolf restoration advocate Rob Edward, president of the Rocky Mountain Action Fund, led the $2.39 million support campaign for the ballot initiative. Edward pointed to the successful reintroduction of wolves 25 years ago at Yellowstone National Park. Today, approximately 1,700 live in Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. A strong government backing of the species’ revitalization is crucial to repair ecological consequences, he says.

“They’re so critical that it’s important for the government to put them back where they have been eradicated,” says Edward. “They were eradicated as part of a multi-decade campaign in an early part of the 1900s; A campaign on behalf of a single industry, and that’s the livestock industry that had no scientific understanding of the ecological consequences.”

Some conservationists point to the beneficial role of wolves as a keystone species. Without their predator presence, elk and deer overgraze by browsing plants and trees to depletion, says Edward.

Backlash Against Reintroduction

The livestock industry, some hunting groups, and the Colorado Farm Bureau united against the proposition that was largely supported by voters in urban areas.

Prop. 114 includes a compensation program that reimburses ranchers for any livestock killed by the predators but offers little economic relief to the state’s immense hunting economy of deer and elk.

“As an apex predator, wolves will drastically reduce elk and deer herds that are already suffering in many parts of the state, leading to decreased hunting and wildlife viewing,” said Patrick Pratt, deputy campaign manager for Coloradans Protecting Wildlife in a Sept. 23 press release.

Colorado recreational hunting is a $1.6 billion business, according to a 2017 report by Southwick Associates, commissioned by the Colorado Parks and Wildlife. The state is home to the largest elk herd in North America.

Some also point to the natural migration of wolves into the state, disputing the need for government intervention. Earlier this year, Colorado Parks and Wildlife identified a group of wolves in Moffat County. The resilient predators often naturally expand their range.

“But even that small group of wolves, which we’ve determined is quite likely a group of siblings, is very unlikely to hold for long-term recovery in western Colorado. They’re just extremely vulnerable to events that cause them to not be able to propagate,” Edward says.

The pack is located in the northwestern corner of the state near the border, where three from the “pioneer pack” were likely killed after crossing into southern Wyoming last summer. The recent delisting of gray wolves from the Endangered Species Act leaves species protection up to the states.

Changes in Gray Wolf Protections

In 1974, the gray wolf became one of the first species protected under the Endangered Species Act. Just last week, the Trump administration announced its plan to remove the gray wolf from the endangered species list across the Lower 48 states following “successful recovery efforts.”

In total, the gray wolf population in the lower 48 states is more than 6,000 wolves, greatly exceeding the combined recovery goals for the Northern Rocky Mountains and Western Great Lakes populations, according to the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service.

Gray wolf protection and management will be up to the states. Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho allow hunters to apply for permits to hunt wolves. States in the upper Midwest like Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Michigan could have regulated wolf hunts in their near future.

The predators have lived in political limbo for years. In 2013 the Obama administration also proposed lifting most of the federal protections for gray wolves in the Lower 48, to no avail. Critics then and now called the decision premature. And as in the past, the decision to delist wolves will likely be challenged in court.

One thing is for certain—regardless of how the delisting decision plays out, Colorado’s divisive vote to approve Prop. 144 is going to have a long-term impact on state wildlife management.

“This one day will be judged as a very monumental conservation victory,” Edward says. “The people of Colorado have decided that they are going to sidestep the political influence of the livestock industry. They are going to tell the state game management agency that it’s time to restore this most important carnivore.”