“Throw some shells in your gun, there’s usually birds right at the start of this field,” I told my buddy Matt. “And if she gets on a bird it’s going to be obvious. She’s not going to stop. You’re going to have to run after her.”

I was referring to my 5-year-old black Lab Otis who, at the first whiff of a pheasant, transforms from mild-mannered couch potato into a homicidal, world-class sprinter. Sure enough, there were birds in the field and they started running as Otis closed in on them. As instructed, Matt chased after her, running flat-out to where the chest-high bluestem hit a mowed field. A hen erupted from the cover, then another hen, then a rooster went airborne, cutting hard left and giving Matt a 35-yard crossing shot. A miss.

“What have you done?” Matt asked, breathing hard, hands on knees as I caught up to him. “Oh, what have you done to this dog?” We’d been hunting for a total of 10 minutes.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Plenty of Labs and other flushing dogs will work slowly and closely (and you can learn about how to train them for that here, but that’s not what this story is about). My cousin has a Lab that hunts cautiously, thoughtfully even. Watching them track down a running rooster is like watching two veteran investigators work a crime scene. But when Otis and I hit a pheasant field, it feels more like we’re about to knock over a 7-Eleven. We’re both excited and a little nervous. I’m not sure exactly what’s going to happen but I’m certain that it’s going to happen quickly, and that at some point I’ll probably have to run.

But here’s the thing: more often than not we kill our birds. Over the years, I’ve learned how to use Otis’ speed and extreme prey drive (okay, wildness) as a strength rather than a hindrance. We kill a lot more roosters than we used to. And over that time I’ve noticed that a lot more folks have flushing dogs like Otis than they do perfectly controlled dogs that never stray outside of shotgun range. It’s admirable to always strive and train for a better bird dog. But it’s practical to learn to hunt well with the one you have. So if you’ve got a wild-ass flushing dog like mine, these tips will help.

Some Commands Cannot Be Broken

There’s a difference between a wild flushing dog and an untrained one. A wild dog might hunt a little too fast and stray out of range on occasion, but will always follow basic commands. An untrained dog doesn’t understand basic commands or will run through them when he feels like it. Otis is whistle-trained and I always hunt with an e-collar on her. Even when she’s birdy, two sharp whistles and a nick on the e-collar will get her back to heel. It’s thrilling to hunt with a wild flushing dog. It’s irresponsible to hunt with an untrained dog. He could chase a bird or a rabbit across a highway. At the very least he’ll blow up your hunt and get your hunting buddies grumbling in anger. You don’t need an elite, professionally-trained hunting dog to have fun in the uplands and kill birds, but don’t take an untrained dog hunting.

Start Them Close

A flushing dog, even a wild-ass one, needs to work close. I try to keep Otis at 10 to 20 yards while she’s quartering back-and-forth searching for scent. A flushing dog that’s running circles around you at 80 yards and kicking up birds out of range is worse than having no dog at all. One trick to get your dog to hunt closer is to actually walk slower. Walking faster as the dog works farther away from you typically only pushes the dog faster. Also, generally, the thicker the cover, the slower you’ll want to hunt.

Trust the Dog

That’s probably the biggest cliché in bird hunting, but so few people actually do it. All the time I see guys grid their way through fields, forcing their dogs to hunt cover that the dog has no interest in. There is no grid work when I hunt with Otis. I’ll start at the downwind side of a block of cover and let her work into the wind. If I can’t park on the downwind side, I’ll walk the edge of the field until I get downwind and then start hunting upwind. I head right for the heart of the field, and from there I let Otis lead the way. If she wants to angle left, but there’s a promising patch of cover to the right, we angle left. I’ll mark likely spots in the field that we miss and circle back to them, but the first move is to let Otis hunt the field however she wants. If she wants to circle back and hit ground we’ve already covered, we do that too. When she starts to get interested, we pick up the pace and I let her hunt in the direction she’s most excited to go, no matter what direction it is (as long as it doesn’t lead us off public land). This method is effective as the season progresses and wily roosters start to pattern hunters. Most bird hunters park in the same spots and work the fields in the same way weekend after weekend. Roosters simply watch the hunters approach from the same direction they always do and then fly or run to safety. Otis and I throw those educated roosters a curveball when we charge into the middle of the field and then split off into whichever direction Otis chooses.

I do most of my bird hunting in Wisconsin and Minnesota where wild bird numbers aren’t always as high as other parts of pheasant country. So if Otis is excited and working hard with her nose down, I know that there are at least birds around, and we’ll spend more time in the area. If we cruise through a field and she never looks excited, we’ll loop back to the truck and hit the next spot.

The single most important time to trust your wild-ass flushing dog is after you’ve shot a bird. Even a rooster that looks stone-cold dead in the air can hit the ground running. If Otis doesn’t come up with the bird immediately, I walk to the spot where the bird fell and drop my hat to mark the location. From there, I just let Otis run free. I’ll give the “dead bird” command, but it’s unnecessary. She knows what her job is now. As long as she’s not headed toward a road, I let her run as far and as fast as she likes. This moment, after all, is where a retriever really shines in the uplands. More often than not, she brings a winged rooster back to hand.

Run Like Hell

When Otis gets on a bird her ears perk forward, the front of her body slinks low to the ground, and she starts snorting in air like a hog. She also starts hunting much, much faster. I call this berserker mode (in Norse mythology, berserkers were warriors who fought in a violent, trance-like fury, and this pretty well describes my dog). It’s hard to miss this birdiness. And this is important because, if you’re going to hunt this way, you need to be able to read your dog precisely. If you mistake true birdiness for just general excitement, you’ll end up spending half the day running after your dog unnecessarily. You won’t know when to whistle her back and when to run after her. But when Otis hits true berserker mode, I do everything I can to keep up with her so she can stay hot on the bird. I’ll sprint when I have to. When she starts coursing at tighter angles I know she’s close to putting up the bird. The longest, most grueling runs are always roosters. If she gets too far away, I whistle her back to me, make her sit, and take a breather. Then we’ll pick up the track and start again. Every now and then I’ll be too late with the whistle and Otis will flush the bird out of range. That’s part of the game. When we get it right, our run ends with a flushed bird right at my feet. The smartest roosters will stay well ahead of Otis and flush from a few hundred yards out. If they stay on public land, we just keep following them, hoping they’ll sit tight or they’ll lead us to other roosters. But very rarely does Otis fail to put the bird up.

Work the Angles

Otis has the incredible sense of smell and God-given speed, but I’ve still got the smarts. When she starts running a pheasant, I’ll look ahead and take a quick assessment of what cover a rooster might want to hold tight in. If there’s a little clump of cattails in the direction Otis is working, I’ll take a direct line it to it. If the cover ends at a cut agricultural field, I’ll head for thickest patch of cover at the end of the line. While Otis burns up ground coursing back and forth, I’ll beeline it to where I think the bird will flush from. And most of the time, I guess right.

Hunting with a Crew

All the strategies I’ve just described work nicely when it’s just me and Otis (and one other hunter who also likes to run). But when you want to take your wild-ass flushing dog out with a group, you’ve got a lot more to consider. This style of hunting does not work well when combined with far-ranging pointers. Basically the pointer will do his job and then your wild flushing dog will run in on the point and put the bird up before you get a chance to get close enough for a shot. This is a fun way to outrage your pointing-dog friends. Here, I’d recommend rotating in dogs. Let the pointers work the big country and then kennel them up and let your crazy dog work the leftover heavy cover.

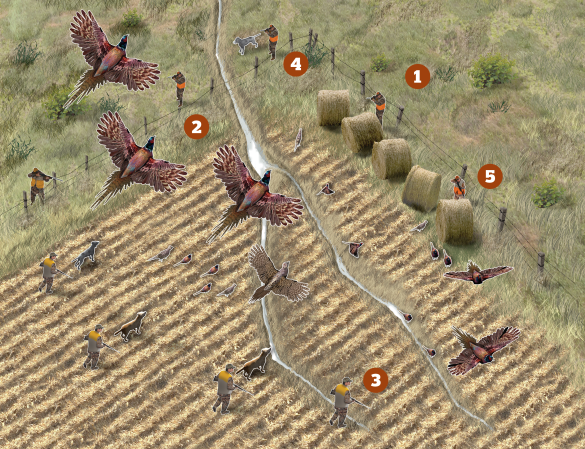

There is one way that hunting with a wild flushing dog can be effective in a big group: blocking a field. This is when a group of hunters pushes a field toward one or two blockers (who post up at the end of the field and shoot birds when they flush wild). This is a nuanced tactic that can be dangerous if not executed properly since you’re pushing birds toward other hunters. But when done safely, it can be incredibly effective. In this situation, it’s okay if your dog works a little too fast because, as long as the field is well blocked, someone’s going to get a shot at a flushing rooster. That said, you still want to keep your dog working close until he gets on a bird.

This exact scenario happened to me a few years ago in South Dakota. A group of us were hunting with an outfitter who was running Labs, two at a time, with about a half-dozen more waiting their turn in dog boxes back at the truck. It was my turn to block, so I snuck down to the end of the field and waited while the dog handler and the other hunters started working my way. Soon enough, birds started exploding from cover and rocketing by me, blurs of wagging tails and lolling tongues not far behind them. Unbeknownst to the dog handler, the kennel gate back at the truck had been left open. All eight Labs were cut loose and were flying through the field at once in a scorched-earth frenzy, right in my direction. It was beautiful, and I could barely reload fast enough.