You and I could drink a lot of root beer as we debate the relative merits of conserving wildlife habitat on public versus private land in America. Efforts on public land have more enduring value, you say, because the places and wildlife that benefit from conservation initiatives are accessible to all Americans. Sure, I might counter, but the best soil, the most reliable water, and the most habitable landscapes in the country are privately owned. There’s a reason all that public land you love is public. Relatively speaking, it’s not especially productive. Directing habitat conservation efforts to private land will have deeper and longer-lasting effects.

But while we debate over our frosty mugs, other folks are figuring out that it’s not an either-or proposition. It’s possible to conserve both public and private habitat, sometimes within the same property.

That’s precisely what the American Prairie Reserve is accomplishing in the remote corner of northeast Montana, where I live. You may have heard of this group and their audacious plan to “re-wild” the shortgrass prairie, converting millions of acres of public rangeland into the nation’s largest wildlife preserve to support bison, prairie dogs, elk, and, eventually, even grizzly bears and wolves. The APR is on its way to achieving this by buying private ranches that have relatively small deeded acreages but that hold leases for much larger expanses of adjacent public lands. These are mostly Bureau of Land Management pastures that the ranchers lease for summer cattle grazing. The APR’s goal is to convert both the private ranchland and public BLM lands to bison range, and eventually to a huge wildlife preserve.

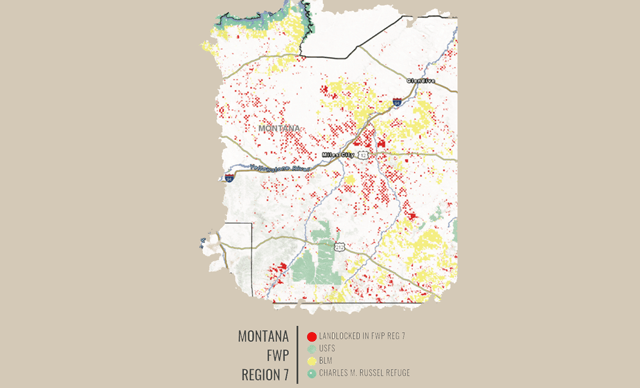

Over the past decade, the APR has accumulated nearly 100,000 acres of private land, and another 310,000 acres of associated federal and state land in northeast Montana. Its mission, according to the APR’s website, is to “acquire and manage approximately 500,000 private acres, which will serve to glue together the roughly 3 million acres of existing public land.” Those adjacent public lands are the elk-rich Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge, which is managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and BLM lands inside the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument.

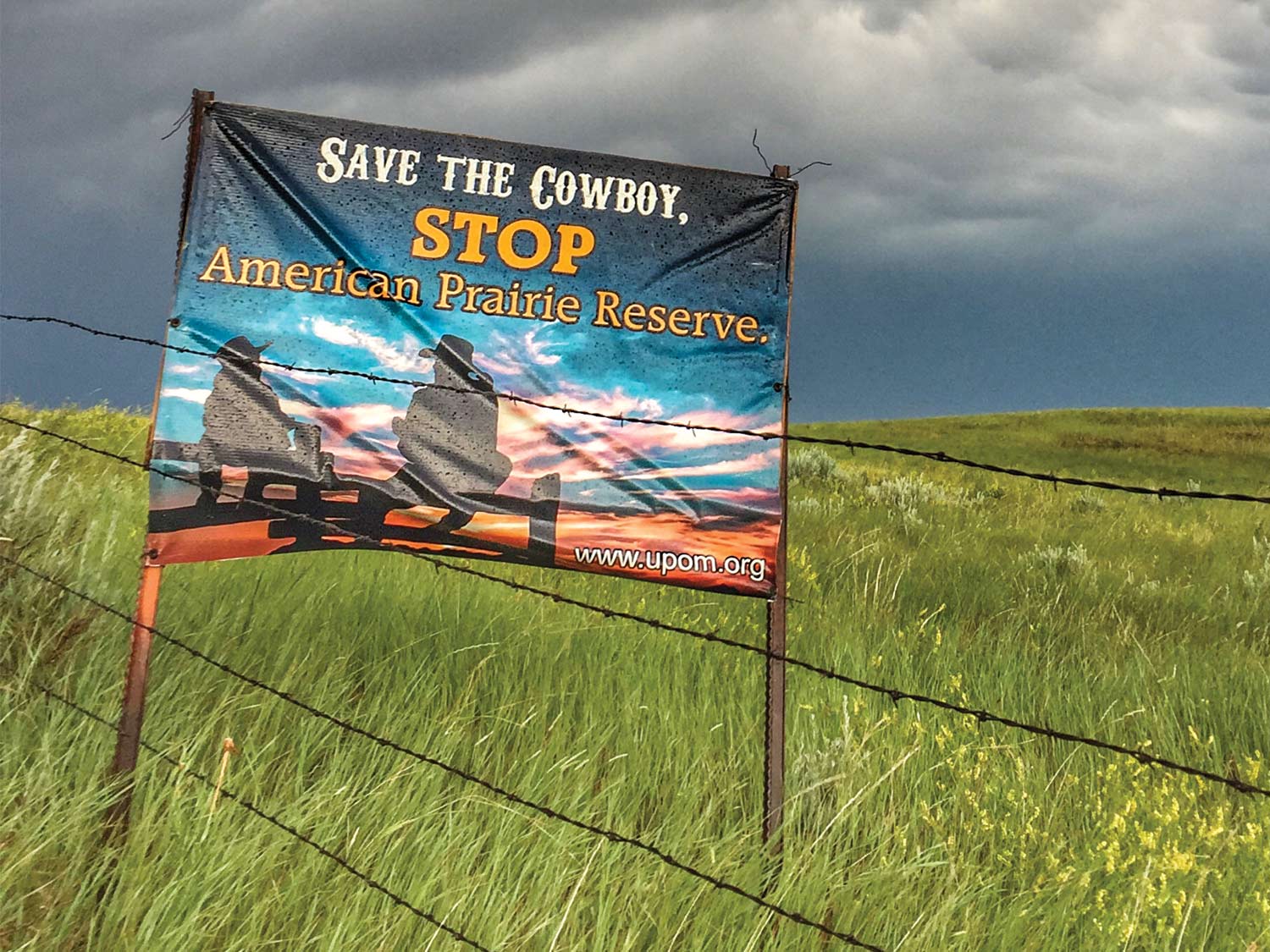

The APR’s initiative has abundant and vocal support and opposition, in more or less equal measure. Advocates (most of whom live elsewhere) claim it’s an ambitious and overdue attempt to heal a century of abuse on some of America’s most fragile but important habitat. Opponents (most of whom live in northeast Montana) claim that the APR is using money from “coastal elites” to displace local ranchers and the rural communities that have grown up around cattle grazing. Besides, they say, those millions of acres of public rangeland are functioning just fine.

We don’t have enough root beer to adequately address both those perspectives, but the APR’s ambition and concept are not going away, and in fact they may be a model for landscape-scale conservation going forward in other places. Here’s why: While the APR has been quietly accumulating land, public funds for conservation have been increasingly hard to secure—they require focused lobbying and frequent advocacy (as Randy Newberg calls for on p. 56). If you belong to a conservation organization, you’ve probably been the recipient of nearly constant calls to action asking you to contact your congressional delegation and demand that they fully fund the federal Land and Water Conservation Fund, or approve Farm Bill conservation titles, or appropriate money for one habitat program, then another.

Private conservationists don’t have to fight those same never-ending advocacy battles to win their funding. Sure, they have to persuade large donors to give money, but those donors often initiate the conversation. That’s because they’re looking for something that can be in even shorter supply than public funds: legacy-scale investment.

As Gib Myers, a former venture capitalist from California, told the Great Falls Tribune, the $2.5 million that he and his wife have given to the preserve—and the Myerses are by no means the APR’s largest benefactors—has a longer-lasting impact than ownership stakes in companies. “This is a real legacy, and so this is our focus,” Myers said of his investment in APR. If he’s correct, and if some philanthropists continue to choose to invest in wildlife habitats rather than art museums or football stadiums, then this trend toward private conservation is likely to accelerate as wealthy baby boomers think about legacy-scale estate planning. The global economic uncertainty caused by the coronavirus crisis is sure to create caution among some large donors, but the APR reported in 2018 that it had more than $5 million in current pledges and another $18 million in conditional gifts, most of it restricted to land acquisition.

That amount of money can buy a lot of ranches, especially in a part of the country where unimproved rangeland sells for less than $500 per acre. That money can also do good work for wildlife, since wild critters don’t know or readily respect the boundaries between private and public land. But as the APR grows in size and influence, questions about its impact on local communities are becoming more pointed. Will the public continue to be able to access public land inside the preserve? Will liberal hunting opportunities be maintained? And will the preserve allow for the continued existence of vibrant rural communities around its periphery?

All those questions bring us back to our root beer conversation, and a different way to look at how we fund wildlife conservation in America. Public funding is hard to win, but the fractious legislative process more or less ensures that they will be used for public benefit. Private funds don’t have that same public-trust obligation, which means that we need to be cautious about how eagerly we solicit or accept contributions that influence things that we hold in common, like our wildlife, our public land, and our traditions of access and transparency.

And that, my friend, is the root of our debate. Are private conservationists working in the public interest? When it comes to the APR, only time will tell.