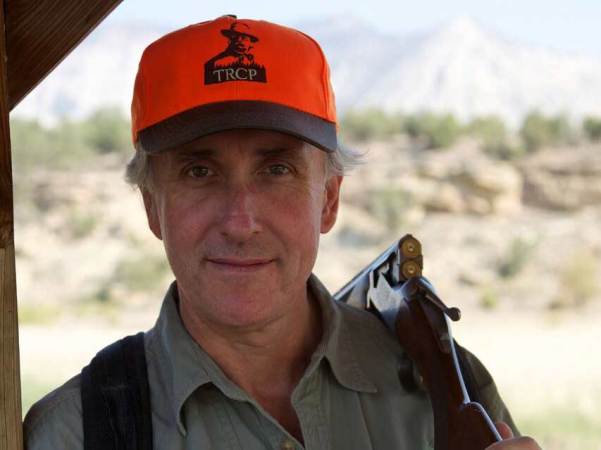

Over the past month, Outdoor Life’s hunting editor Andrew McKean has had two opportunities to interview Secretary of the Interior David Bernhardt. The first interview was a wide-ranging conversation about topics as varied as CWD funding, actions that federal agencies are taking to prepare public lands for climate change, and the status of acting BLM director William Perry Pendley.

The second interview detailed a new BLM designation called Backcountry Conservation Areas that aim to perpetuate sportsmen’s access to public lands but to give managers tools to improve wildlife habitat and improve public recreational opportunities. These BCAs got their first showing earlier this month in the BLM’s proposed Resource Management Plans for the Lewistown and Missoula areas in Montana as well as the Four Rivers Field Office in southwest Idaho.

The new land designation is intended to “promote public access to support wildlife-dependent recreation and hunting opportunities and facilitate the long-term maintenance of big-game wildlife populations,” said the BLM in a statement. Bernhardt told McKean the new designation is designed to “perpetuate traditional access and to take care of our best big-game habitat, using migration mapping and other information to improve the habitat even more. Other uses, like oil and gas development or mining, are still allowed but they’re secondary to those two things. We think it’s an important way to recognize the value of some of these lands to wildlife.”

The BCAs will curtail some uses, including minimizing surface occupancy of critical lands and regulating viewsheds, but lands in BCAs will generally be open to traditional multiple uses, including motorized travel and the use of mechanized equipment for habitat improvement projects. Backcountry Conservation Areas are planned as land-use designations in other resource management plans scheduled to be released later this year and into 2021.

Later, Bernhardt sat down for a wide-ranging interview. Here are some sound bites from that discussion, plus a lightly edited transcript of the full interview.

Acting BLM Director

Outdoor Life: The acting director of the Bureau of Land Management, one of the largest agencies in the Department of the Interior, is—like you—a former oil-and-gas industry lawyer, and is on the record advocating for government’s divestment of federal lands. Many critics of William Perry Pendley have suggested that, because he has not been recommended for permanent BLM director, that his record could keep him from being confirmed. First, what’s the basis of your support for Pendley, and second, will you forward his name for consideration as permanent BLM director?

David Berhardt: Perry Pendley is doing a great job and he will continue to do a great job. I know people have views about statements he’s made about public lands, but I will tell you that as a manager, those views are not views that I find relevant in terms of him running BLM. Here’s why. Perry is a lawyer. Whatever people think about Perry, it’s unquestionable that he’s been a lawyer for a long time in his career. Lawyers understand their clients’ position. Perry is also a Marine. Marines understand the chain of command. Perry knows unquestionably how important it is to me and to the president that we maintain our position that the public lands will remain in public hands and be managed by us in the best way that they can be. There is no way Perry is deviating from that an iota.

You asked if we should we have somebody confirmed? My view on that is yes. But let me tell you, I know exactly how long the background process takes. I know exactly what goes into getting a candidate nominated. At the end of the day, someone will be nominated. That person will go through the process. But I’m pretty good when it comes to counting votes. Go look at the people who said I wouldn’t get confirmed…

Climate Resiliency

OL: Regardless of whether you think that it’s human-caused, climate change is affecting much of how we manage public lands. Wildfires have increased in duration and intensity, water has increasingly become a scarce commodity in some regions, and species are under stress. How are you managing agencies in the department to be resilient given such profound changes in the operating landscape?

DB: We make decisions at the Department of the Interior that have to consider three things. First, every decision has a legal component, because we are administrators of the law. Second, we have to consider information, or facts. There’s the facts we have and the facts we don’t have. Third, there’s a realm of policy discretion, and that’s determined by elections.

When it comes to information, it’s customary for us to consult our biologists. In Endangered Species Act discussions, we want a biologist to forecast into what’s called the ‘foreseeable future.’ Now, when you ask a biologist to explain the foreseeable future to me, you get a different answer than if you ask a geologist about the foreseeable future. Geological time frames tend to be different. Now if you say what’s the foreseeable future to a lawyer, you get a different answer altogether than what the biologist would tell you. At the end of the day, the decision that matters in that context is the lawyer’s view, because the lawyer is who will explain it to the court.

Both of those are different than this: We think things are happening in the environment and we need to think about those things when we make our decisions. For example, if you look at our water-management plans, you’ll see that they’ve recognized things are changing. If you look at our fire treatment plans, you’ll see that we’re recognizing that fires seem to be occurring in a more dramatic fashion and our fire season seems to be lengthening. That may affect, for example, my decisions on seasonal employees for fighting fires. Look at our leasing plans and you’d see that we’re thinking about this stuff. We’re not ignoring it. We’re not ignoring the changes we’re seeing. I have a lot of credibility in this space because I’m the only person on the planet who has been involved in listing a species largely based on science and climate science. I was involved in the listing of the polar bear. People may not like it, but that was the first one of dealing with climate science.

The BLM’s Move to Grand Junction

OL: You stirred up controversy when you proposed—and then enacted—a move of senior managers at the BLM from Washington, DC to a remote office in Grand Junction, Colorado. You have said that move was for the good of the resource. Does this action anticipate other moves for Department of the Interior agencies?

DB: My first conversation with (previous Interior Secretary) Ryan Zinke was about a massive reorganization that he wanted to pursue. For him, it came down to a philosophy as much anything, about how can you better serve the American people but also how we can change the mindset of the department a little bit. The more time I spent with Zinke’s idea, the more I became a believer in the sensibility of the Department of the Interior’s headquarters migrating in some way.

Today, we have the ability to communicate very well with an office that’s several hundred miles away. We have very high-priced rent in D.C. and our costs in D.C. are higher because we pay people a locality differential. When you look at these numbers, they really add up. Number two, some of our best managers often don’t want to come to D.C. The people who work in Interior generally are people who love the land. They love the outdoors. They’re drawn to Interior for reasons other than a nice cubicle office without a window near the National’s stadium. So, we’ve had trouble recruiting positions. What I’ve seen is that when we’ve moved them out, we’re getting better initial inquiries.

Before I even authorized a move, I asked: do we need this job? I ask that because fundamentally I believe we need more boots on the ground. We need more resources in the field. Our field offices are strapped. That’s where most of our work actually takes place.

When it comes to our Senior Executive Service, people like state directors for the BLM and regional directors at Fish and Wildlife Service, our upper echelon of managers. I say to them: You really need to understand my priorities, because you’re accountable for them. If you look at my job description in law, I supervise all public business of the Department of Interior. What does that mean? The word “all” is used and “public business.” So, I would say it’s pretty broad. My view is that if you’re a state director, you’re supervising all public business of the BLM in your state, and if you’re not, I’m going to be all in your business, and that’s not what you want. So, they’re accountable for understanding what policies I have, because that’s my discretion, not theirs. And they’re learning that.

WIld-Horse Management

OL: Wild horses and burros are one of the great management failures of the Department of the Interior. Their range has increased and their protected status allows them to increase in populations and further degrade habitat for native wildlife. What are you doing to address the wild-horse issue?

DB: It’s a big challenge. When I was here before [Bernhardt served in the George W. Bush administration], wild horses were outta control. We had a crisis. We had 45,000 horses. You know how many we have today? 70,000 plus another 20,000 in retirement homes. We just got $21 million from Congress, and we have a limited period of time to try to demonstrate that we can do good things with this $21 million. We spend about $80 million a year on wild horses, and we’re gonna do that forever probably. But if we can demonstrate that what we do with this extra money gets things going in the right direction, we may be about to turn a corner, but we’re a long way from saying that we’ve solved it.

CWD Funding

OL: Chronic wasting disease is one of the most devastating wildlife diseases in our history. What is Interior doing to understand and slow the spread of CWD?

DB: When I was at Interior before, our budget for CWD was $8 million. Last year it was $700,000. When I was here before, there were 5 or 8 states with CWD. Now it’s 26 and maybe growing. We need to work with state wildlife managers. Where I think there’s a lot of opportunities, like on best practices, encouraging people not to use urine-based attractants, things like that. A lot of science needs to go into it. There’s roles for Agriculture, there’s roles for us, and there’s roles for the state.

I got a conversation started last year. The appropriations are starting. We need to work on it. For me, it dovetails very closely with ensuring that [hunting and fishing] participation numbers remain good. We just have to manage the situation the best we can. These are very complicated structures, these prions and proteins. It’s not an easy thing, but we just cannot ignore it for 10 years.

We have a CWD task force within the department. I’m the first secretary in a long time to have a career science advisor. I tasked him with putting a group together within the Department and on top of that working with the Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies and with [Department of] Agriculture to begin to develop best practices. One area where we can play, if a state has practices they want to use, we can probably work to use those on federal land, too, within that state.