The doe trotted past, too quickly for a shot, and disappointment swamped our blind. The new hunter beside me finally had a deer within range, and he thought he’d blown it. If I’d ever questioned Arc’s interest in hunting before, his intent was unmistakable now: He really wanted to kill a deer.

One minute later, a dozen does ran into our little plot, a buck on their heels. With minimal coaching, Arc folded his first deer with a single shot. By nightfall, three more hunters from our group had killed their first deer, and the landowner who hosted us had four fewer does on his property.

But the easy success of that Missouri hunt belies what’s actually a staggering problem all over the U.S. Our current recruitment efforts are well meaning, but we have a long way to go before we save hunting.

Big Problem, Slow Response

Hunter numbers have been declining from an all-time high in the early ’80s. And when the alarm bells started ringing more than a decade ago, our collective response time was abysmal. First, the hunting industry had to admit there was a problem. Next, we had to understand what we’d been doing wrong. Now that state agencies and conservation groups have finally identified which programs work, they’re trying to act on that intel. Meanwhile, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, we’ve lost 255,195 hunters nationwide between 2016 and 2020.

The good news? This country is already chock-full of folks ready to sign up. Adults from varied ethnic, cultural, and geographic backgrounds want to learn to hunt, and they’re willing to spend money to do it. Surging license sales from turkey season during the COVID-19 lockdowns suggest there’s a growing interest in hunting, and the self-sufficiency it provides. But state game agencies aren’t engaging nearly enough new folks, or capturing their potential license dollars, and the private sector of the hunting industry isn’t doing much better.

Read Next: Will Coronavirus Get More People into Hunting?

Old Dogs and New Tricks

The overarching problem is that many state agencies are too inflexible, too bogged down by bureaucracy to implement the necessary changes quickly.

Hank Forester, QDMA’s hunting heritage programs manager, is skeptical that agency veterans will make the changes we need. “Culture change really has to come down from the top—something that we’re just not seeing,” he says. “Recruitment professionals are typically at the bottom of the totem pole.”

“There have to be big cultural changes, and that can’t happen from one person trying to force change in the agency,” says Jenifer Wisniewski, chief of communications and outreach at the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency. Her state’s dedicated approach to hunter recruitment appears to be working, and other states should consider following suit. “Usually if you don’t have 30 years in an agency, then you’re [treated like] a nobody. The new kid isn’t going to make sweeping changes.”

We’re also dealing with capacity issues. Inside Philadelphia city limits last fall, 20 first-timers ranging from 13 to 73 years old participated in a successful bowhunt. A dozen mentors helped, and the response was overwhelmingly positive. The trouble is, those hunters were selected from more than 100 applicants. That’s 80-plus aspiring hunters who were rejected.

And this is only a snapshot of the larger problem. Of the 30,000-plus students who pass hunter ed annually in Pennsylvania, fewer than half actually buy a hunting license that same year. Meanwhile, the state has lost nearly 50,000 hunters over the last five years. Adding 20 new hunters is great, but it’s a little like bandaging a papercut instead of addressing the hemorrhaging chainsaw wound in your leg.

Now the state is trying to address its mentoring capacity problems with videos and digital classes. “It’s a big, complex puzzle of how to meet the needs of [beginners],” says Derek Stoner, hunter outreach coordinator of the state’s Game Commission and an organizer of the Philadelphia bowhunt. “And it’s probably never going to be met by in-person classes.”

Private Party, Public Good

It’s unrealistic to expect agencies—large bureaucracies that are slow to shift priorities—to solve recruitment on their own. Especially when we have millions of active hunters to take up the cause, and a billion-dollar hunting industry that also relies on hunter spending. Forester suspects for-profit recruitment is the future, and that whoever figures out how to scale these programs will also make money. Like, say, selling adventure, learn-to-hunt packages to urbanites.

Eric Dinger, an entrepreneur who created the mentoring app Powderhook, thinks it’s a mistake to task states with recruitment. Other industries don’t rely on the government to grow their customers, so why should hunters?

“We know hunting is fun,” Dinger says. “And we’ve still never figured out how to get one million hunters to each invite one person hunting. That’s really the missing piece, and I don’t know that an agency or an app or a product will fix that. I think that’s a culture change. We need veteran hunters thinking it’s cooler to invite someone to shoot their first deer than it is to shoot a deer themselves.”

One of the objections from current hunters is that there isn’t enough land or wildlife to go around as it is, and if we add thousands of hunters to the landscape, that problem only gets worse. “We have a limited resource, and we don’t need 100,000 more deer hunters,” Wisniewski says of Tennessee. “But small game? Even trapping. Those are kind of a lost art, and that’s something we’re encouraging.”

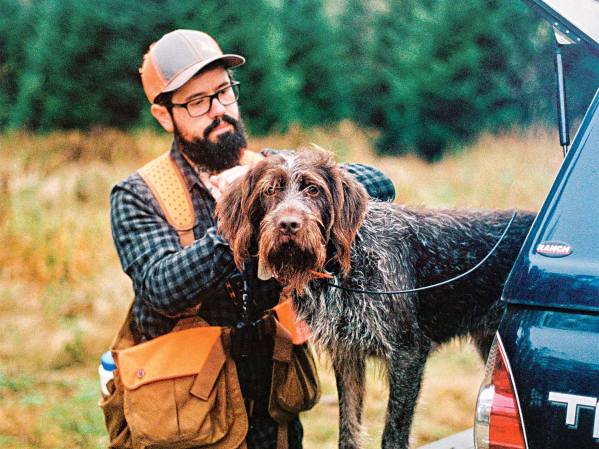

Besides, research shows that new hunters don’t care about all the things traditional hunters do—like killing big bucks. There are opportunities for private landowners who need help shooting does each season to offer access to new, local hunters.

And that’s just what happened on our Missouri doe hunt last fall. That night, with every tag punched, we all filtered into the skinning shed, where the differences between rookies and veterans faded. Everyone was talking at once, asking questions and swapping stories. One hunter, who used to work at a game-processing shop, was showing Arc tricks for peeling the hide off his doe. I sat back with my beer and just watched the butchering, laughing, and bullshitting unfold. It was as natural as any deer camp, and it was impossible to tell who was having a better time: the new hunters or the old ones.