“I got one!” my buddy (a new hunter) told me as soon as I picked up the phone. He was talking about a cow moose that he’d just killed with his bow, filling a local semi-urban, archery-only draw permit. He quickly gave me the details, and although his hunt was completely legal, the cow died near a fairly busy road, so I told him to make sure and have his license and permit handy because he was sure to get a visit from the wildlife troopers (Alaska’s game law enforcement agency). In hindsight, I wish I’d have told him to call them and tell them about it himself. Soon enough he was visited by three different troopers, lights flashing. This is an uncomfortable situation for anyone, regardless of outcome. Even the most seasoned, ethical hunter will begin to second-guess themselves under interrogation.

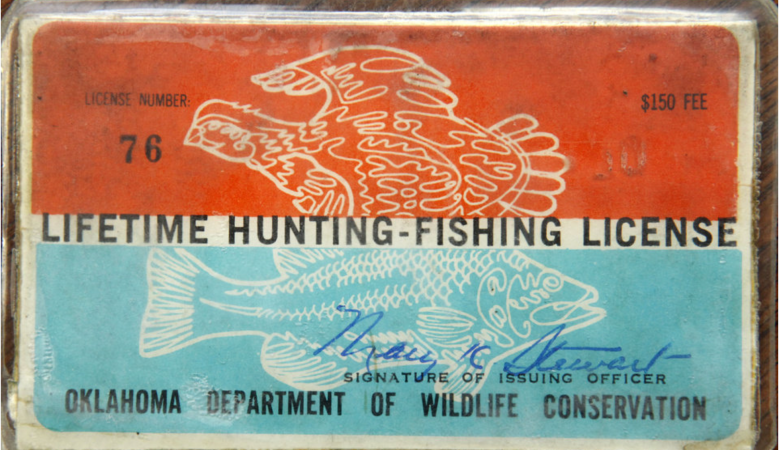

As hunters, we have a unique interface with law enforcement. We are regularly license-checked, and law-abiding hunters typically have a direct understanding of how important wildlife law enforcement is. We know that many of the agents, wardens, and troopers have the same passion for the outdoors that we do. There are always exceptions, but in my experience most wildlife enforcement officers can relate to hunters and just want to make sure everyone is playing by the rules. Naturally, everyone will have their own opinion on whether or not they’ve had positive or negative interactions with wildlife law enforcement. That said, we don’t want to throw them under the bus for simply doing their jobs. When you’re hunting in close proximity to other people, you can expect to be visited by the local trooper or warden. This is all pretty standard.

However, I’ve been noticing a growing issue in situations like this. It seems that we live in an increasingly Orwellian society full of snitches and tattle-tales. Now, don’t get me wrong, actual wildlife violations should absolutely be reported. Perhaps a more contemporary way to say this is that even here in Fairbanks, Alaska, there are “Karens” everywhere. These folks see something they don’t like, and think “might” not be legal, or they simply see an opportunity to cause someone else an inconvenience, and they feel obligated to call the authorities. I don’t like this situation, but it’s the reality. If you’re hunting where people can see what you’re doing, you’re bound to be reported, it’s just a fact of life. Depending on the situation, there are several things you can to do save yourself time and headaches, as well as allowing law enforcement to focus on actual poachers and law breakers.

When to Call Ahead

Sometimes, it’s a good idea to call your local wildlife enforcement agent or warden before you ever go hunting. Call ahead when you know you’re going to be hunting in a spot or manner that an unwitting passerby might think “could” be illegal. In some places, this is actually required and saves a lot of hassle. When I was a kid growing up in Colorado, you could use spotlights to hunt predators at night, but on public land, you needed to call the warden before you went (to prevent folks from jacklighting deer). Even if you do end up getting checked, it’s likely that since they already know you’re going to be there and they know what you’re doing, the stop will go quickly and smoothly. This can save you a tremendous headache and perhaps even save you from a disrupted hunt. I’m not saying that law enforcement needs to keep tabs on our every move, but in a situation where you’re likely to encounter them anyway, you might as well make it easier on everyone and let them know what you’re up to.

But sometimes you don’t know exactly when or where an opportunity will present itself, and it might just happen to be in sight of a busy road. As in my buddy’s case, it wouldn’t hurt to immediately call and inform them of where he was, what happened, and that he had everything in order. Sometimes, they might not send anyone at all, and if they do, it will be the correct officer, who already has an idea of what’s going on. This often turns out to be a positive experience. However, when a dispatcher is going purely off of what the crazy cat lady has told them, they may send the SWAT team out. It might take the officers awhile for them to figure out that nothing illegal actually happened. Once, while checking permitted beaver traps (in Fairbanks) with an AK fish and game employee, we were approached tactically by city police officers. They were called and told that we were shooting in a highly populated area (and who knows what else). After we cleared things up with the cops, we got back to our truck and found state wildlife troopers waiting for us because the same person had also called them and told them an even different story.

Ultimately, you can’t control the Karens, but you can make sure that you’re doing everything by the book, and doing your best to make wildlife officers’ jobs a little easier. In my experience, when you’re open and truthful with wildlife officers they treat you fairly and you’ll have a positive encounter. But if it seems like you’re trying to be secretive or cagey, the officers will key in on that and potentially try to write you up for even the smallest infraction. So know the rules, follow them to the letter, and talk to your game wardens—then enjoy your hunt knowing you’re on the right side of the law.