I wouldn’t have met Lee Livingston, or have gotten to count him as a lifelong friend, if I hadn’t hired him to guide me to a Wyoming bighorn sheep. On the other hand, I could have killed that ram without Lee, a registered outfitter based in Cody. Maybe it would have taken me longer. Maybe I would have settled for a smaller specimen. But as an accomplished big-game hunter, I could have found a way.

Only Wyoming wouldn’t let me.

As long as there’s been federally managed wilderness in Wyoming, the state has required nonresidents to hire a licensed guide or be accompanied by a resident in order to hunt big-game species in designated wilderness areas. It’s not a small amount of space. Wyoming boasts 14 wilderness areas totaling more than 3 million acres of federally managed public land.

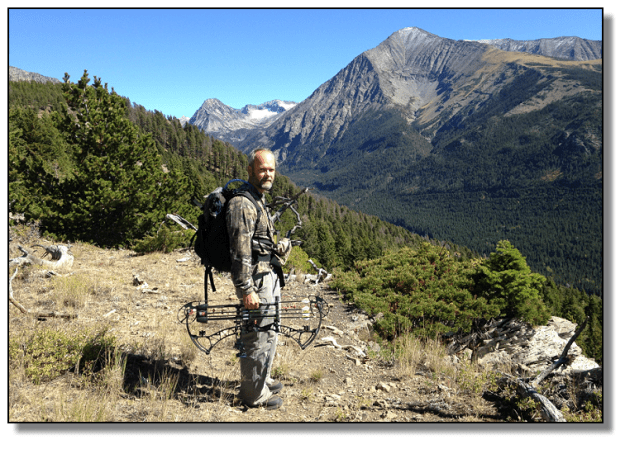

I don’t need a guide to access that land in the summer with a fishing rod. I can hike and camp entirely guide-free with my family. But if I shoulder a rifle or a bow, I’m breaking the law if I enter that public land without a guide.

It’s a rule that Keiran O’Brien knows all too well. O’Brien, now 82 years old and still living in his hometown of Eden Prairie, Minnesota, was 47 and an elk-hunting machine when he and two brothers packed into the Teton Wilderness in 1984. A game warden ticketed them all for hunting without a licensed guide. O’Brien appealed, and the case went all the way to the Wyoming Supreme Court.

“It was bullshit then, and it’s bullshit now,” O’Brien said in an interview last fall. “For nine or 10 months of the year, you can hike naked in the Wyoming wilderness, and nobody messes with you. But for two months of big-game season, you’re a criminal if you hunt your own public land without a guide. It’s un-American, and it’s designed to keep outfitters in business.”

O’Brien’s appeal maintained this law violated three clauses of the U.S. Constitution: the equal-protections clause that ensures the rights of U.S. citizens are maintained in all states; the immunities clause that ensures residents of one state are afforded rights granted by all states; and the supremacy clause that requires states to adhere to federal law—in this case, that of the National Wilderness Preservation System.

Read Next: Hunting Bighorn Sheep in the Wyoming High-Country

Wyoming’s highest court disagreed on all counts. In a split 3-2 decision, the court ruled in 1986 that O’Brien, and every other nonresident big-game hunter, must have either a licensed guide or a qualified state resident take them into wilderness areas. The court maintained that the rule ensures public safety, since guides are familiar with the dangers of the wilderness and how to keep their clients safe. Besides, the court said, states are within their rights to limit other aspects of hunting, including the number of big-game tags that are reserved for residents.

But Wyoming’s wilderness rule has come under renewed scrutiny as the national “keep it public” movement gains momentum. Do states have the authority to exclude Americans from their own public land, regardless of their state of residency or which activity they pursue?

“It’s a tradition that’s rooted in a system where folks profit off the allocation of those [big-game] tags,” says Tim Brass, the state policy and field operations director for Backcountry Hunters & Anglers, which hasn’t taken a position on the guiding law. “Embedded traditions are hard to change. The safety aspect doesn’t hold water at all. Hunters hunt safely in the wilderness in every other state.”