We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

As America’s hunters prepare for the woods and fields this autumn, the U.S. Army is gearing up for an even longer and more uncertain season. Military evaluators this fall are assessing what the Army calls its Next Generation Squad Weapon (NGSW), a replacement for the venerable M4 carbine and the M249 light machine gun.

If its predecessor as the everyday-carry weapon for America’s fighting force is a guide, then this new rifle could be used in combat missions for the next 40 years. The current M4A1, chambered in 5.56mm, has been the workhorse of GI grunts since the Vietnam War. The M249 light machine gun, also known as the Squad Automatic Weapon, or SAW, has been around nearly as long.

We actually know precious little about this new squad weapon, since military procurement is shrouded in classified secrecy. But here’s what we do know: It will be chambered in 6.8mm. The projectile it fires will be a copper slug tipped with steel to pierce the body armor of “peer adversaries” at long range. And it will be capable of belt-feeding and the high rates of fire required by the successor to the SAW, as well as slower rates of fire but more precisely placed shots from squad-deployed carbines. Also in the Army’s requirements: Despite shooting a heavier bullet, the gun, together with its ammo, must be 30 percent lighter than the current platform firing the 62-grain 5.56mm load. The Army’s new 6.8 is not to be confused with the 6.8 SPC, based on a .30 Remington case. The external dimensions of the new 6.8 are bigger, both in diameter and length, and require a new magazine configuration, according to sources.

We also know that three consortiums are in the running for the final bid. They are General Dynamics Ordnance, Tactical Systems, and the ammunition maker True Velocity; SIG Sauer and its partners; and the triad of Textron Systems, Heckler & Koch, and Olin Winchester.

We’re covering this arms race because if the history of military small-arms procurement teaches us anything, it’s that technology developed for the battlefield eventually shows up in the deer stand. The Springfield Rifle, the .30/06, the AR platform, the .223/5.56 round, nearly all of John Browning’s inventions, plus hundreds more innovations were developed for military use. How soon will we see the 6.8 cartridge and associated weapons platforms come to our sporting-goods stores?

Very soon. Those of you paying attention to the porous membrane between civilian and military ordnance have seen evidence of this Army squad-weapon project in the commercial space. SIG Sauer’s new chambering of .277 SIG Fury, introduced earlier this year, is a child of the Army’s new-weapon search and hints at SIG Sauer’s contribution: a traditional brass cartridge case that’s fitted with a steel rim and cartridge head. The steel base allows the cartridge to shed weight but handle higher pressures to generate muzzle velocities well above those achievable by all-brass cases.

Why does heightened pressure tolerance matter? Because it allows a rifle to achieve desired velocities in a shorter barrel. The end result is a lighter weapon than conventional brass-cased ammo would allow. The proposal from General Dynamics includes a cartridge designed by True Velocity that features a polymer composite case.

The Textron team’s contribution is also built around a groundbreaking cartridge design. Called a case-telescoped (CT) cartridge, the technology uses an enclosed plastic case to contain the propellant and bullet, achieving 30 percent weight reduction while also dissipating the heat of rapid-fire operation. Wayne Prender, Textron’s senior vice president for applied technologies, declined to comment on the specifics of the firing system or on the design of the rifles that chamber the new ammunition, which is being manufactured by Olin Winchester.

“What I can tell you is that we threw out the rule book when it came to this ammunition design,” Prender says. “We did not try to refine or to tweak an existing platform, but instead we took a new approach with the plastic polymer. Some of the advantages are in weight, but at higher pressures, plastic simply performs better than brass or other metals. We measure that performance advantage in increased rate of fire, muzzle velocity, and extended range. Now, each of those is relatively easy to maximize individually, but our challenge has been to maximize them collectively, while also significantly reducing the weight of the firing system.”

Textron and its partners aren’t new to the CT ammunition business. A decade ago, the company developed a case-telescoped polymer cartridge in 5.56mm for the Army and then scaled it up to 7.62mm. But the 6.8 project required rethinking the weapon itself, which will be produced by H&K, and partnering with an ammunition maker that could provide the millions of rounds the Army’s $12 million annual contract requires. That’s where Olin Winchester enters the picture. The company recently won a 10-year, $28 million contract to operate the military’s Lake City Ammunition Plant near Kansas City, Missouri, where it will manufacture the Army’s 6.8 bullet, and also the CT round, if Textron wins the NGSW contract.

“We acquired crucial experience developing the technology for the CT round, but in order to support an Army at war, we need the ability to scale,” Prender says. “Olin’s capability to scale shines even brighter with the recent win of the Lake City plant.”

Might we someday see case-telescoped plastic cartridges loaded for deer hunters in Winchester’s signature red-and-black boxes? Prender didn’t want to speculate. But he did note that the advantages of the NGSW, including weight reduction and the downrange energy of the round, won’t be only for soldiers.

“The weight reduction alone is a huge advantage, whether for mobile soldiers or hunters,” says Prender. “Simply carrying a weapon and the brass ammo can be burdensome and affects a soldier’s livelihood. It keeps them from moving as fast or agilely as needed—or to shoot as accurately as they need to because they’re tired. And it’s not just foot soldiers. We are addressing the need for a rifle and AR replacement now, but there is growth potential beyond that. Replacing medium and heavy machine gun systems is in front of us, and I can anticipate other applications that might size up the projectile in the CT platform. As an example, weight is extremely important for a helicopter-deployed weapon.”

As for the 6.8mm, Prender says it balances flight stability, accuracy, and downrange energy better than any of the 6mm cartridges. And if Textron wins the contract, plastic-cased ammunition could show up in soldiers’ hands by fall 2023. And maybe in the rifles of deer hunters a few years after that.

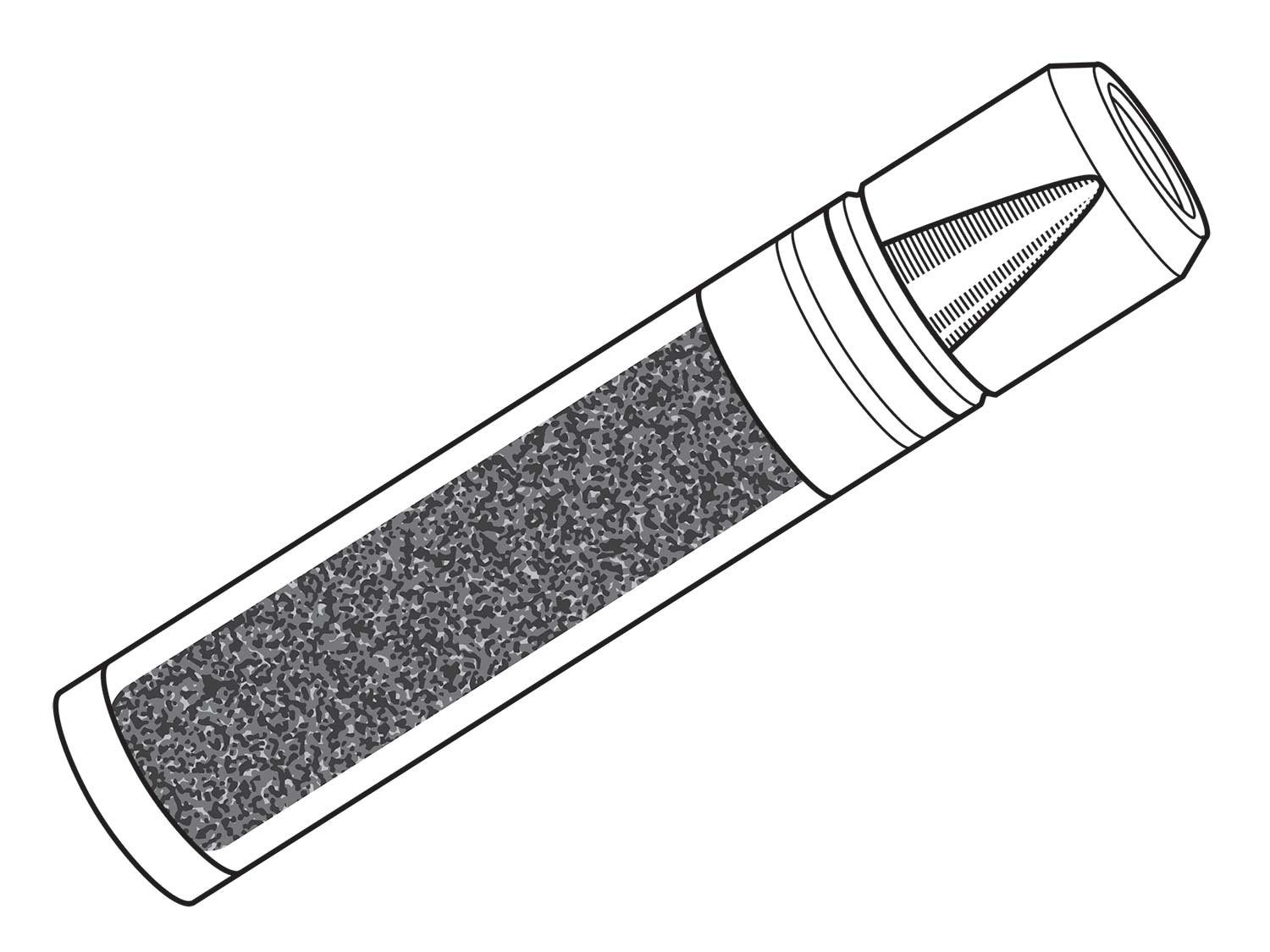

And… There Will Be a Muzzleloader Hunting Boom

Real talk—most of us who hunt with muzzleloaders don’t wear buckskins or moccasins; we hunt with them because they give us longer seasons or because regulations prohibit centerfire rifles. And most of the state agencies that write the rules around muzzleloader use aren’t dedicated to preserving the heritage of old flintlocks. These agencies want to hit their management objectives, which, at least in the Midwest and Northeast, often means harvesting more deer and getting more hunters in the field. The product designers at Federal understand these realities well, and introduced a product earlier this year that makes muzzleloading a hell of a lot easier. The FireStick is a capsule that comes preloaded with powder that you load through the gun’s breech. The system is much faster and infinitely cleaner, and it’s super simple to use (though it can be used only with Traditions’ new NitroFire gun). Federal is betting that the simplicity will bring new folks into the game. The product will be legal for hunting seasons in about 30 states this fall. “As soon as the industry announced it, our hunters were asking, ‘Can I use this?’ ” says Peter Novotny, the assistant chief of Ohio DNR. So the state changed its regs this summer to legalize the FireStick. Look for other states to follow suit. —Alex Robinson