We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

My wife’s family has an incredible cabin in a very remote, and scenic part of northern Montana. It’s one of our favorite places in the entire world, but a recent spate of security issues threatened to derail our ability to visit. We were being inundated with animal and human predators coming on to the property. It was concerning, and I worried for the safety of my wife, her family, our dogs, and myself. To be able to keep enjoying our trips north, we needed to find a way to feel safe up there, no matter what. And, using a mix of high- and low-tech solutions, I think we made that happen. Here’s what we did to make the cabin as secure as possible.

The Problem

My wife and I are the closest members of the family to the cabin, but live a 300-mile drive away in Bozeman. So, even though we try and get there as often as we can, it sits empty for long stretches of time. And, out there in the middle of nowhere, there are no neighbors, nor a consistent law enforcement presence. While there’s nothing of any real value inside, my in-laws have spent a lot of time and effort fixing the place up, so it looks nicer than most other properties in the area.

When we’re not there, the cabin is a target for thieves. When we are there, no external help is available on any kind of practical timeline. Particularly in winter (our favorite time to visit), the weather is frequently extreme. Wind, ice, and snow can knock out communications, or power, and make it impossible even to leave the property.

Montana is home to plenty of big critters like grizzly bears, wolves, mountain lions, and moose. But, in most parts of the state, seeing any of those animals is actually relatively rare. But at the cabin, any number of those animals can walk across the deck at any time, which could result in a dangerous situation.

If all that isn’t enough, communities in the area have recently been ravaged by methamphetamine addiction, and the violent crime that often accompanies it. A couple of break-ins occurred, a high-profile drug raid was conducted nearby, and trail cameras we placed on the property to pick up photos of visiting animals started capturing prowlers of the two-legged variety.

Make It Look Like Someone is Always Home

The first thing we did was hire a local guy to perform regular maintenance. In the winter, he plows the driveway and keeps the lights on. Spring, summer, and fall he mows the grass, clears brush, and removes dead trees. Hopefully all that drives home the fact that people care about the place, makes it look more frequently occupied, and creates a regular human presence that might deter anyone casing the area.

We also updated the no trespassing signs and the ones for the cabin’s alarm system, making sure they would remain prominently visible even with snow accumulation. We also added signs warning of video surveillance. A street lamp installed on a utility pole outside the cabin lights the entire area at night.

If nothing else, hopefully this is enough to keep casual trespassers, and people who might only commit crimes of opportunity away—teenagers, poachers, vagrants, etc. It’s safe to assume that anyone ignoring the signs, and climbing a locked gate to enter a well lit property is pretty committed to a nefarious course of action, and that filter affords us the confidence to deal with those people a little more severely.

Up-To-The-Minute Misinformation

Before I took all this on, my father-in-law installed two of these wireless driveway alarms. Due to steep terrain, a lake, and dense brush, that driveway is the only easy way to approach the cabin. Each chimes a different alarm bell inside, notifying us when something first starts down that driveway, then when it enters the immediate area of the cabin.

I say “something,” because anything larger than a squirrel will trigger these chimes. And that’s problematic because the amount of false alarms they create instills apathy real fast.

Late one night, shortly after security at the cabin really devolved, the alarm at the top of the driveway started to go off over and over. There was no way to tell if it was a car full of troublemakers, the fox that lives by the garbage cans, or something else. So, I had to run up there in my Y-fronts, pistol in one hand and flashlight in the other to see what was going on. I am very happy to report that I found nothing and was able to return safely to bed, because the next morning I discovered pie plate-sized grizzly tracks in the driveway, right underneath the first motion sensor, accompanied by a set of cub prints. That would have gone very badly had momma bear been startled by the sight of me in my undies.

I liked the idea of the perimeter alarms, but they were worse than useless without being able to know what was triggering them. What we needed was a camera system located at the site of each alarm, connected to some sort of easily-accessed monitor inside the cabin. All it took was one look at the price of having a wired security camera system installed to come up with a better idea: cellular game cameras.

We know from much trial and error that the only cellular phone signal available at the cabin comes from Verizon. (We do thankfully have satellite Internet there.) But, that one bar of service is provided by a tower across the border in Canada. A whole lot of Googling suggested that Moultrie made a camera that should work, but at $300, I didn’t want to spend a bunch of money buying several without knowing for sure. So, I bought a single camera on Amazon, familiarized myself with it at home, then brought it up to the cabin on our next visit. Through some miracle, the XV-7000i actually says it has five full bars of service there, has no problem transmitting data through Canada, and is able to upload any images it captures to Moultrie’s cloud server in real time. Strapped to a tree above one of the perimeter alarms, it makes images available on the accompanying smartphone app by the time I’m able to pick up my phone. And all for $14-a-month with no contract.

That’s a hugely empowering amount of information when we’re at the cabin, and it’s enabled me to stay in bed rather than go chase that fox around the dark woods. What’s surprising is how much peace of mind and practicality that camera delivers when we’re not there, too. The entire family seems to be checking the Moultrie app constantly, filling up the group text thread with photos of all the cool animals it captures. During a recent storm, it even showed us a falling tree and its aftermath, and we were able to get the handyman over there soon after to cut it up for firewood. Images are uploaded to the app in a fairly low-resolution format that’s friendly to data speed, but you can simply request the upload of any of those images in high resolution, easily enabling you to identify human faces at distance, or read license plates. There’s an image sequence of a car full of teenagers on there, first creeping down the driveway, then fleeing once they saw me tearing out of the cabin after them, this time fully clothed. The photos are clear enough you can see the fear painted on their faces.

I’ve since ordered more cameras, and fitted them all inside CamLockBoxes. Those are made from steel, precisely fit to a specific make and model of camera, and attach to a tree using a cable lock. They appear to have no effect on the strength of the data signal reaching the cameras. I’m sure a determined thief could eventually defeat the lockbox or cable and steal or disable the camera, but not before having multiple photos of their face uploaded to a cloud server. One advantage of doing all this in a very rural area is that, while there’s not much law enforcement around, there’s also very few people. If I get a photo of a trespasser, I can take it to cops with a reasonable expectation that they’re going to be able to identify the person in it, and without a whole lot else to do but go and talk to them about that.

The cameras now overlap, covering every side of the cabin, and all approaches to it. Powered by batteries, they continue to work even if the cabin’s power or Internet goes out. You’ll forgive me for not sharing photos of the cabin itself, ones that could give away its location, or which inappropriately identify intruders.

I Bought a Large Caliber Gun

If you aren’t familiar with grizzly bear attacks, you might not be aware that there’s a controversy around the efficacy of bear spray versus that of firearms. It all rests on two studies done using disparate methodologies by a single scientist, that he once told me weren’t meant to be compared at all. But, of course, people compare them, and mix them with their feelings about animal conservation and guns to arrive at conclusions that simply aren’t realistic.

Guns kill grizzly bears. But, you don’t always want or need to kill a grizzly bear. A bear that’s sniffing around for food, or just moseying about, can typically be run off with bear spray. A bear that’s protecting its cubs, or a kill, may not be so easily deterred. Around the cabin, we’re mostly going to be encountering bears chasing tasty smells. So, we go to great lengths to avoid leaving, say, a greasy grill out after dinner, and eliminate or secure any other potential attractants.

Still, as the cub tracks in our driveway indicated, we do run the risk of encountering a bear that’s very motivated to kill us. For that reason, we need to make sure the guns we carry at and around the cabin are capable of dealing with the largest predator in North America, even if we may also need to use them on the most dangerous predator in the world.

A study conducted by Dean Weingarten demonstrates that grizzly bears can be killed by a firearm of virtually any caliber. The variable that concerns me is time. In a life-or-death situation with a bear, it’s going to happen very fast. So, shooting a bear only to give it plenty of time to carry on with killing you before it goes on to die a while later is not the solution I’m looking for.

All of the training we’ve taken, and all of the bear attack survivors and experts I’ve talked to agree on one thing: no handgun is powerful enough to immediately render a bear harmless. No matter the caliber, all handguns (or shotguns) do is poke holes. Poking more of those holes is better than poking fewer of them. So, we carry semiautomatic handguns, and run heavy, powerful hard cast lead loads designed to maximize penetration through them. More holes, deeper holes.

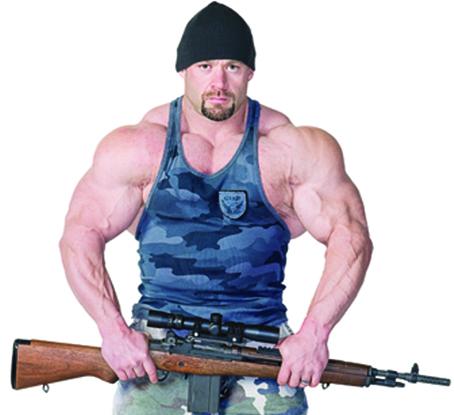

Still, those are a last-ditch option that may not save your life. If I ever have to run out of the cabin in the middle of the night, in my underwear, ever again, I want to be carrying a gun that requires no asterisk or modifier. I want to be carrying something capable of killing anything I shoot with it in an authoritative and immediate manner. Enter the Marlin 1895.

Reading writers like David Petzal and John B. Snow, I came to the conclusion that .45-70 offered the performance I was looking for, especially with modern loads, and the 1895 in GBL form promised a sexy looking gun that was compact, and fast-handling—perfect for using in and around a cabin, or as a truck gun. I ordered one, and set about playing around with configurations and loads.

Chasing maximum performance, a 325-grain Hornady Leverevolution was the first choice. Using a spire-point bullet, it offers more consistent accuracy than the flat or round-tipped alternatives, and a polymer avoids the tendency for a round detonating the one in front of it in the tubular magazine under recoil. But, after a couple of trips to the range, I was unable to produce groups smaller than 3 inches at 100 yards. I’m used to modern, one-hole hunting rifles, so I reached out to Neal Emery, who runs marketing at Hornady for help.

Emery told me that the 325-grain FTX is designed to be more of an expander than a penetrator—sort of your ultimate drop-a-deer-where-it-stands round than something appropriate for predator defense. That wasn’t much help on accuracy, but it did point me in the right direction on effectiveness in this particular application. Going back to Petzal’s work, I found his recommendation for 430-grain Buffalo Bore hard cast for bear work. Out of my 18.5-inch barrel, it should be delivering in excess of 3,000 foot-pounds of energy, in a round capable of penetrating anything it impacts, without expansion. I wouldn’t want to shoot this around other homes or people for fear of over penetration, but out in the middle of nowhere, it should resolve any arguments I need it to.

Of course, a round is only as good as your ability to put it on target. Given that most of our security concerns come at night, and at distances far under 100 yards, I needed to find an optic capable of delivering fast, precise shots, and the ability to see at night. With half a mind to use this rifle for hunting at some point, I opted for a variable-power scope, rather than a red dot. Made from the company’s highest quality glass, the Leupold VX-5HD 1-5x24mm retains the ability to run the gun with both eyes open, but for those 100-yard or more shots, it also gives me the ability to dial in a little magnification for more precise shot placement. The whole idea with fancy glass is that it gathers light better than your eyes can alone, so this scope also provides clarity in low-light conditions that might otherwise be marginal. It mounts to the gun with a quick release, so if you have any concerns about glass in hard conditions, the iron sights provide a backup. The sight picture is so crisp, and so clear on this thing that I’m shooting as fast as I could with a dot, just with more precise aim only crosshairs can deliver.

Adding a scope to a lever rifle is easy. Mounting a light is harder. I tried a light mount from Wild West Guns, but it uses the magazine band’s set screw for retention, meaning it needs to be mounted way out at the far end of your barrel. That impairs weight distribution, and makes it hard to operate the light with your support hand. The Hill People Gear light mount is far better, simply clamping to the magazine tube anywhere you’d like. It includes an MLOK slot on the bottom side, and a length of Picatinny rail, enabling you to mount any light on the planet. To that, I fitted a Streamlight TLR-1 HPL. That’s the company’s most powerful light that’ll fit unobtrusively on a standard pistol or carbine, paired with a large reflector designed to gather and focus light for a very tight beam pattern. It projects the LED’s 1,000 lumens all the way out to 500 yards, with enough peripheral light to retain good situational awareness.

Together, that scope and light are an effective combination. I’m able to keep the light off until I need it, then flick it on with a finger on my support hand, and acquire a target in the same instant. There’s so much light that there’s no confusion in what I’m shooting at, nor an ability for any target to outrun my vision. I still can’t group this thing under three inches at 100 yards, but hey, the torso of an average adult human is a full 18 inches across. There’s room for error.

I’m currently copying that build with an 1894 chambered in .44 magnum for my wife. She’s a better shot than me, but only weighs 100 pounds, so is recoil sensitive. This being 2020, I’m hoping to run 230-grain Buffalo Bore (the heaviest bullet an 1894 can stabilize) through it, but none is currently available. It won’t be as immediately effective as the .45-70, but she can shoot it, and it should be substantially more powerful than a revolver running the same ammunition.

Our Pets Offer Protection

I ran all this past a retired Army Ranger buddy. He and I have spent enough time together outdoors that I trust him both to have a handle on my capabilities, and to provide honest feedback on ways in which I can get myself killed.

Griff was impressed by the perimeter alarms and the cameras, but less enthused by the idea of me going up against what could possibly be multiple armed assailants, all on my own. “My rule is never to get into a gun fight without at least four-to-one odds,” he told me. “That way you can move, reload, and provide covering fire.” But my entire goal here is to be able to enjoy the cabin with my wife, without bringing Griff along as a third wheel.

I was dismayed for a second, then remembered that I was sitting on the couch with three large, aggressive dogs spread across my lap. So I asked him if they counted in that ratio. “Yeah, you’ll be fine,” he responded.

Read Next: Why a Shotgun Is a Great Option for Home Defense—Plus 3 Guns You Should Buy

Thinking about bears, attacks are often caused by surprise. You get close to a bear that’s protecting something, and like a shark, its method of evaluating the threat you pose is to bite your face off. Look at the most recent incident in Montana, and you’ll see that the bear didn’t realize a father and son were nearby until they were right on top of it. But, with the dogs along, not only do we take wind direction out of the equation by adding noses (even if the wind is blowing from the bear to us, we’re now equipped with receivers for that), we also add a circle of disruption that encompasses at least a 100-yard circumference from our own location. It becomes far less likely that one of us humans will be the one that draws the bear initially, giving us more time to respond in whatever manner we end up deeming appropriate.

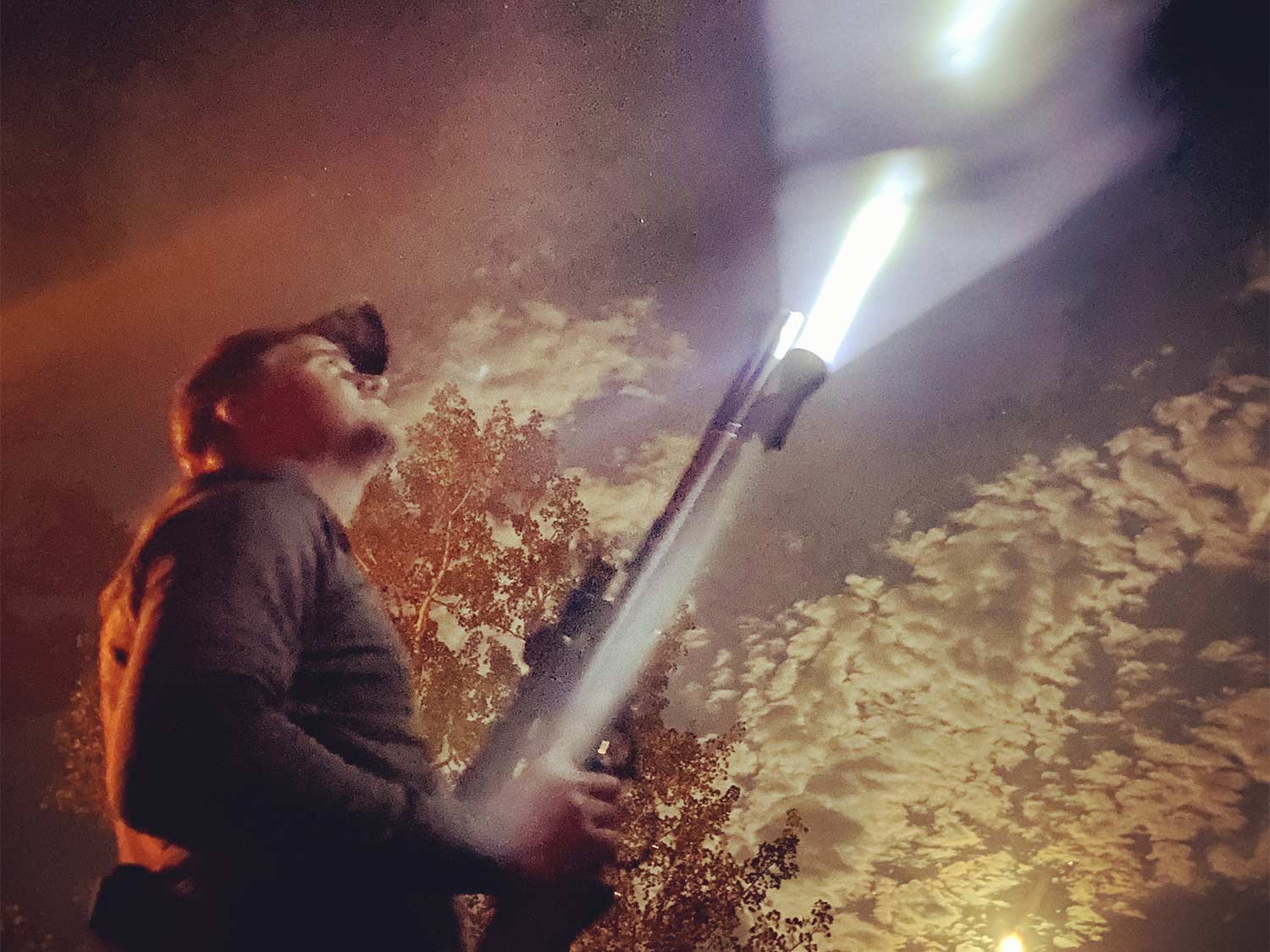

With humans, dogs augment our alarm system, add a significant degree of deterrence, and amplify any threat I pose to an intruder. One guy blinding you with a spotlight on what looks like a really big rifle turns into not being able to see as three sets of jaws come tearing at you through the night, making a godawful racket along the way. Adding three sets of ears, and three noses to that equation pretty much ruins any meth head’s ability to hide.

In both scenarios, the dogs net us valuable seconds with which to make more informed decisions, or just place more rounds on target. What happens in the likely event any of that harms the dog? Well, dogs are the definition of impermanence. I figure allowing one to go out doing its job is the highest honor you can pay it.

Of course, I don’t want to lose one of my little buddies. The entire idea with creating a security plan this layered, and focusing it so strongly around deterrence and information is that it hopefully enables us to avoid trouble. I feel like I’ve made the worst case scenario as unlikely as possible, but am also confident that if that worst case does come knocking, I’m prepared.