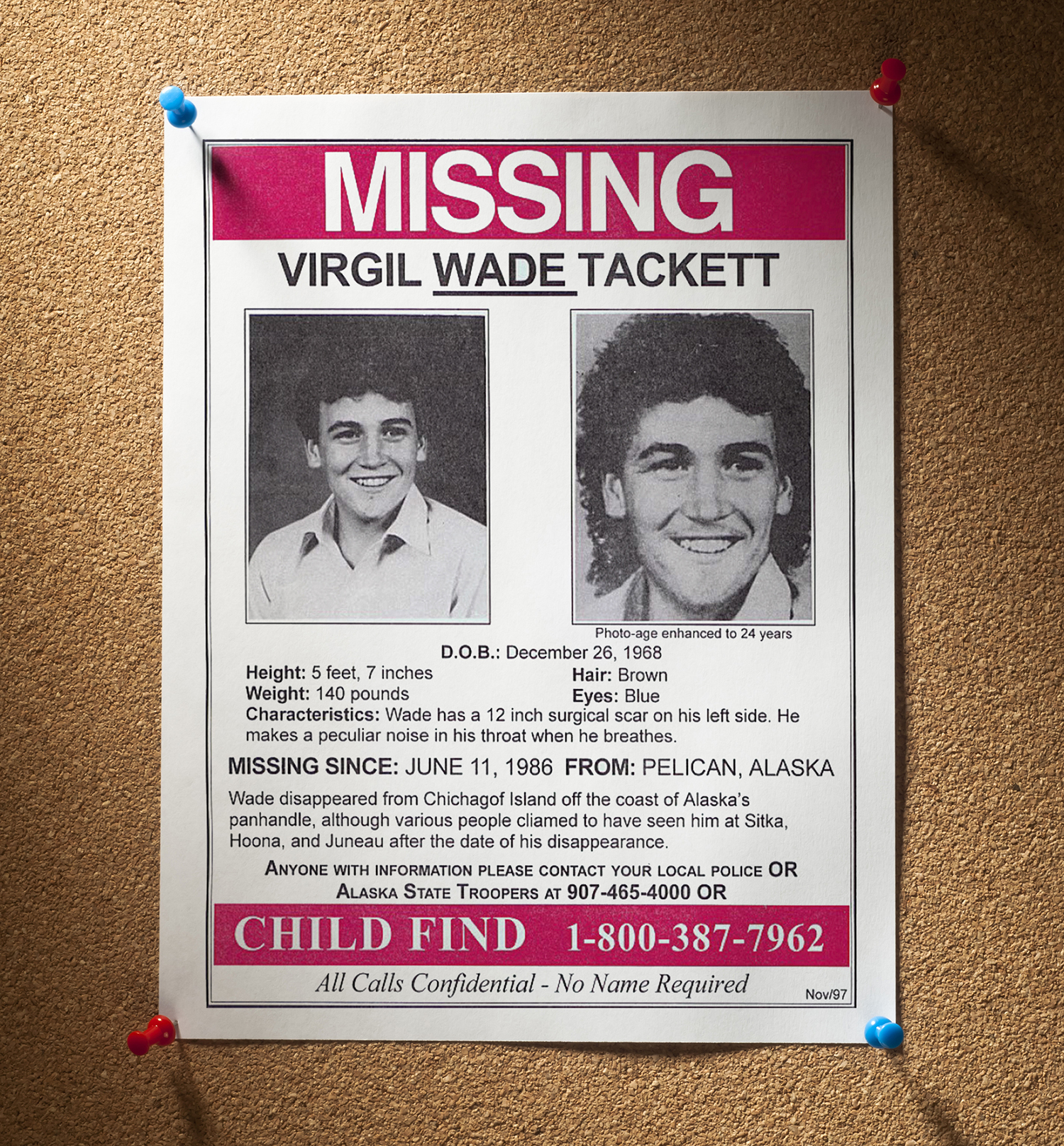

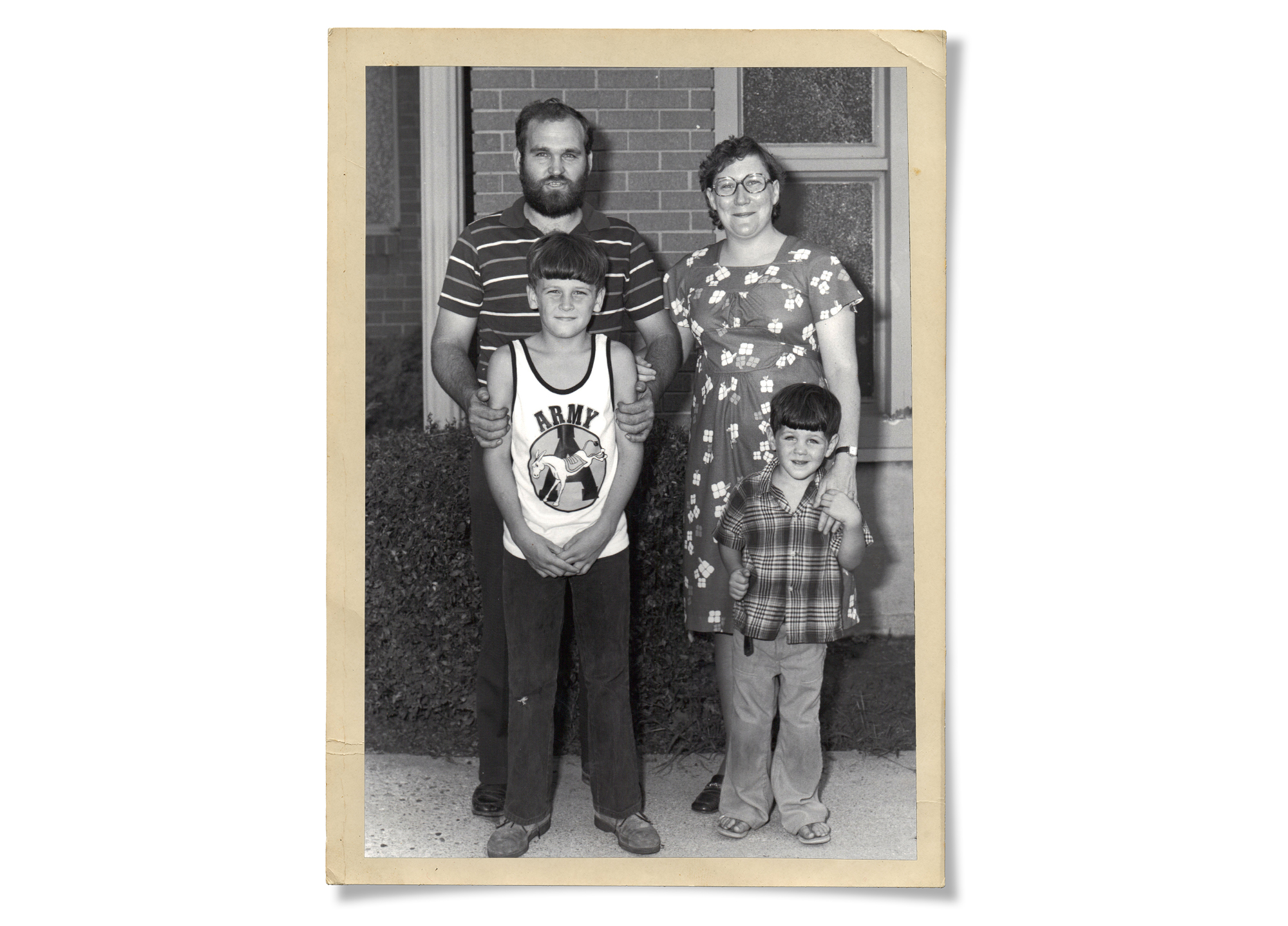

IN LATE MAY 1986, 17-year-old Virgil “Wade” Tackett flew from Ohio to Southeast Alaska, thinking he had a job on a family friend’s commercial fishing boat. But when he reached Sitka on Baranof Island, a community of 8,000 people, he discovered there had been a mix-up.

Another boy, Nick, had been giving the deck-handing job. The family friends promised to help Wade find work at a seafood processing plant or on a fish-buying scow. Wade worked a few days off-loading halibut at Sitka and then spent some time exploring the town before boating with his family friends and Nick about 100 miles north, to Pelican, to help them get ready for the Dungeness crab season.

The weather was sunny and calm on June 11. The boys didn’t have much work to do, so Wade and Nick took a 14-foot skiff out to explore the area around Pelican. Nick would later tell the state trooper who investigated the case that after a hike on Yakobi Island to an old mine, then a picnic on Junction Island, he decided to stay on shore while Wade went out to explore with the skiff. Wade never came back.

An hour or two after he last saw Wade, Nick hailed a passing boat. The Good Samaritan and Nick found the skiff less than a mile away, nosed against the shore. The throttle was near full-open, and the outboard was dead. They notified the Coast Guard and, that evening, searchers began combing the shoreline and the water. Aside from a single oar found the following day, there was no sign of Wade.

The investigating Alaska State Trooper ruled that Wade had drowned. It was an open-and-shut case for anyone used to the harsh realities of Alaska’s waters. The ocean is dangerous. Commercial fishing in Alaska is one of the deadliest occupations in the country: During the last decade, an average of 24 commercial fishermen have drowned in Alaska each year, according to the CDC. An additional average of 20 noncommercial boaters drown annually in the state. Wade was not wearing a PFD, one of the details about their son’s disappearance that Wade’s parents had a hard time believing. But almost no Alaska commercial fishermen wear PFDs, largely because it’s harder to work in one. There’s also the prevalent belief that if you fall into the frigid water, you’re dead either way.

Despite the fact that the circumstances of Wade’s disappearance weren’t all that unusual, his case turned into one of Alaska’s stranger missing person sagas. It involved psychics, talk shows, politicians, and alleged sightings of the missing boy that would be reported for years to come.

A Family Searches for Clues

On June 18, 1986, Virgil and Mary Tackett arrived in Pelican from Ohio, hoping to find their son alive or at least his body. They found neither. Worse, their trip to Alaska left them with more questions than answers. The Tacketts rejected the Alaska State Trooper’s conclusion that their son had fallen out of the skiff and drowned. They suspected foul play and clung to the hope that their son was alive. Accounts reveal that Mary, in particular, directed a lot of frustration and blame at Nick and the trooper who had investigated the case.

For author R.W. Swartz, who lost his own brother in a drowning accident in 1973, Wade’s disappearance struck a hard chord. He published the book “Cold Water Cold Hearts: A Mother’s Search for Her Son Missing in Alaska” about the 17-year-old’s disappearance last year, which has renewed public interest in Wade’s case.

“The State Trooper did his job,” Swartz told me over the phone. “Nick was probably traumatized by it all.”

When the Tacketts returned home, they wrote long letters to Ohio Congressman Bob McEwen, Alaska Governor William Sheffield, and U.S. Attorney General Harold M. Brown criticizing the investigation and asking for help with their son’s disappearance. The offices of McEwen and Sheffield and the Alaska State Troopers all scrambled, trying to answer their questions and offer some closure. Numerous members of Tackett’s community wrote Rep. McEwen asking that the investigation be reopened. McEwen was sympathetic and responded in force, requesting three times that the FBI get involved. The Tacketts contacted newspaper reporters, as well as TV and radio stations. In December 1987, Cincinnati Enquirer columnist Camilla Warrick published a five-part series on Wade’s disappearance. The Tacketts began talks with the TV show Unsolved Mysteries, though the program strung the family along for years and ultimately never featured their son’s story.

Supernatural Encounters

Willing to try anything, Mary began speaking to alleged psychics. First, she asked a friend that was considered to be clairvoyant. In a letter printed in Swartz’s book from Mary to Chuck Busby, the village public safety officer in Pelican, she wrote that the psychic told her Wade may have been kidnapped, enslaved, and forced to work in a mine:

“She did not say he is in a gold mine but that he is with others who have been thought missing and that they are doing some sort of work. I cannot count the times she has told us that Wade is coming home. She says she can see him here, that he will be found and that this is bigger than we could ever guess.”

Mary then contacted Frances Cannon, a private investigator and celebrity mystic known as the Singing Psychic, who regularly made the rounds on shows, including Howard Stern’s and David Letterman’s, and professed to be a “psychic to the stars” for pop icons like Michael Jackson. She apparently developed her powers after almost being killed by a logging truck that crashed into her car. Cannon, who had also claimed to have helped find hundreds of missing children, was a guest on a Cincinnati radio show when Mary called in. After they spoke, Cannon threw everything she had at finding Wade. She was convinced the teen was alive but a victim of child slavery who was forced to run drugs.

After Cannon had a vision of Mt. Edgecumbe on Kruzof Island, just across the sound from Sitka, she flew to the small city and soon began encountering people who, she reported, had seen Wade Tackett around town. When the Sitka Sentinel interviewed Cannon not long after she’d arrived, she said she had already talked to 30 people who’d seen the missing teen.

Cannon made quite the impression on Sitka’s residents, including Dave Kanosh, who was in high school at the time. Kanosh, a Tlingit culture-bearer who is now in his fifties, remembers wondering if Cannon was mentally sound and if she was exploiting the family.

Almost four decades later, Kanosh is still haunted by Wade. He’d met the boy a week or so before he disappeared, when Wade had approached him in the library and wanted to talk about a variety of topics, including Native legends. Some of what he asked made Kanosh uncomfortable, including stories about the Tlingit bogeyman, the Kóoshdaa Káa. What makes Kanosh even more uncomfortable is that he is one of numerous people who believe they saw Wade after he disappeared. Kanosh’s encounter occurred in August 1986.

“He seemed disoriented. He was asking people where he was. Initially, I had thought him drunk, but his speech was not slurred. A man and woman were walking along. The lady carried a bag. She put down her bag as he approached, seeing if he was okay,” Kanosh said before recalling the first time he met Wade. “His fascination with Tlingit legends—in particular the Kóoshdaa Káa—still chills me.”

The Kóoshdaa Káa means different things to different people in Southeast Alaska, but none of them are pleasant. It evokes strong superstitions among some, particularly commercial fisherman. Most often it’s considered an evil spirit that preys upon and possesses those who become lost in a literal or metaphorical sense. The spirit turns those lost souls into reflections of their former selves. The Tlingit used to believe that anyone lost at sea would become the victim of the Kóoshdaa Káa. Sometimes the lost would come back for a brief while, like revenants returning to haunt the world of the living. In certain cases, if victims could be made to remember their humanness by a shaman, they could be brought back to their human selves.

Questionable Sources

The Singing Psychic had not been in Sitka long before she had her own sighting of Wade in a hotel.

“I saw the boy myself,” Cannon is quoted as saying in Swartz’s book. “I was unable to retain him. He backed away from me afraid and wild eyed. I was in the lobby where kids play games. Large Natives in the doorway grabbed him and ran.”

Cannon immediately called the Tacketts with the news. Virgil and a friend flew to Sitka as quick as they could. Upon meeting Cannon, Virgil lost confidence in her sighting. But then she whisked him away on a wild-goose chase that culminated in a meeting with a self-described shaman named MiMi Donthiner. Over several drinks at a bar, Donthiner cryptically told the bereaved father that she herself was taking care of Wade.

“Mimi said she would let Virgil see Wade but then changed her mind,” wrote Swartz, “saying again that he might not be able to stand the shock: ‘If you can wait a few years, he would probably be healed and returned if he wanted to be. Do you want a half a boy back or a whole boy back?’”

At the same time Virgil was in Sitka, his wife called Dolores “Dolly” Whaley, founder and CEO of Missing Children of America, to see if she had any information on her son. Whaley, who was based in Anchorage, had never heard of the case. But when she went back through her files she was surprised to find three calls her agency had received inquiring about a boy named Wade. They’d been made in October and December 1986, and the following January. The callers, who allegedly had Tlingit accents, asked if anyone was looking for Wade. The first two callers said that he was being taken care of. The last caller said Wade was not doing well.

The October call was placed before any missing-person fliers about Wade had made it to Alaska, according to Cincinnati Enquirer columnist Camilla Warrick. Mary Tackett and Dolly were shocked by the messages, and Dolly threw herself into the search for Wade.

While Cannon was considered by some to be a certifiable, and Donthiner’s intentions were also questionable, Virgil still went to the Sitka police station and made a detailed report of everything the two women told him. Before leaving Alaska, Cannon chartered a helicopter to Kruzof Island and the base of Mt. Edgecumbe, as well as an abandoned World War II outpost. She and Virgil poked around without finding any sign of Wade.

(Strangely enough, a human skeleton was discovered in that area in 2020. Investigators are still trying to identify the remains, though they believe they’re from the past 50 years. The skeleton likely belongs to an individual who was between 30 and 50 years old and was of Native or Hispanic ancestry, which appears to rule Wade out since he was a white teenager.)

Shortly after Cannon’s return from Sitka, she wrote a letter to President Regan asking him to get involved with the case. Swartz printed excerpts of it in his book, including the following: “I believe that narcotics from other countries are shipped in through Sitka. Kids are used to pass drugs and for sacrifices in the Tlingit Indian culture. Some kind of trade between Moonies, Nazis, devil worshippers who have infiltrated the Natives.”

The Many Sightings of Wade Tackett

People began seeing Wade around Alaska. Most claimed something appeared wrong with him, like he had amnesia. Some reported that he lived in Hoonah, a community about 75 miles by boat from Pelican. Dave Kanosh points out that another characteristic of the Kóoshdaa Káa is that the spirit will occasionally assume the form of the lost person, either to confuse people or to lure them away too.

A year after her original series was published in the Cincinnati Enquirer, Warrick wrote a follow-up column, asking: “But who then is that other boy who has been sighted nearly a dozen times in such Alaskan villages as Sitka? The one who matches Wade’s description right down to his wavy brown hair and pure blue eyes. Who gave him the shirt like the one Wade had that was bright yellow with a pineapple on the chest? Where does he belong? Why does he look so disoriented? What do his tears mean?”

For a few years, there were more sightings of Wade in Southeast Alaska, but eventually the trail went cold. The Tacketts did their best to face their loss and move forward. Then the Oprah Winfrey Show called asking if they, alongside other parents of missing children, would be on the show. After their segment aired, the family received what they thought was a solid tip.

Months before, social worker and counselor Lynn Brooks claimed to have seen Wade with a traveling work crew in a bar in Yellowknife, the capital of the Northwest Territories. A 1990 article for the Cincinnati Enquirer describes their meeting:

“Brooks talked to him about three hours. ‘He was different, very quiet, much younger, kind of lost,’ she said. ‘He nursed the same beer all evening.’ He told her he was from Michigan. He loved wildlife. His name? ‘Wayne.’ Brooks is convinced he was Wade, now 21. She detailed the encounter to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, who have opened their own case and consider it a valid sighting.”

Other sightings across Canada followed until the late 1990s without leading anywhere. They soon petered out and left the Tacketts, who’d had their hopes rekindled, all the more miserable. Mary Tackett was subsequently quoted in the news as saying, “You’ll go to the gates of hell to find your kid.”

That, and then some, is what she did until she died in 2010.

An Unsolved Mystery

Swartz thinks that many of the psychics who “helped” look for Wade probably meant well, despite ultimately causing the family more pain. He points out that Cannon never charged the family for her services, though she spent significant time and resources on the case.

After dedicating years of his own life to Wade Tackett’s disappearance, Swartz is convinced the 17-year-old drowned on June 11, 1986—the day he went missing. Even so, Swartz admits to a Wade sighting of his own long after the boy had gone missing. It was in Gustavus, Alaska, during the small town’s July Fourth festivities. He hadn’t yet heard of Wade at the time. Later, when he took on the book about the missing teen, he was struck by how much the man in Gustavus had looked like an artist’s rendition of Wade’s appearance as an adult.

Twenty-one years after Swartz’s brother drowned, the author received a strange package in the mail to his desk at the 32nd Street Naval Station in San Diego. It was addressed to his deceased brother at an address in the California desert. Swartz, thinking it was a mistake, put the package back in the mail, only to find it back on his desk three days later. Once again, he returned it to the military post office with a note not to return it. Days later, it had appeared on his desk a third time.

Swartz was mystified by the package. His brother’s body had been recovered. There had been open viewing during the funeral. The return address was in Kamloops, British Columbia. The customs slip said the box contained a flag, though Swartz never opened itNonetheless, it gnawed at him until he convinced his family to take a weekend trip into the desert with him. He didn’t reveal the true reason why he wanted to make the drive.

“As I drove by the address in the desert, there was a group of people in the yard having a barbecue, and none of them could have been my brother, or even a family relation. Feeling foolish, I drove home,” Swartz wrote. “Even after years, the loss of my brother controlled what I did.”

It’s easy to conclude that Wade’s story was the result of a collective insanity, that all the sightings were mass delusions akin to catching a glimpse of Bigfoot at the edge of suburbia or the Virgin Mary in clouds. Without a body to put to rest, even when there is no other logical conclusion than death, people can imagine and cling to the most improbable of alternatives. The Alaska State Troopers Active Missing Persons Bulletins webpage shows the faces of more than 150 missing people, each with a gut-wrenching, heartbreaking story. In his photo, Wade is smiling, looking mostly innocent—if a bit mischievous. He looks like a boy destined to take full advantage of life. It’s no wonder he was so hard to let go of.

Read more OL+ stories.