I saw my first elk track during the summer of 1962. My class had been doing field work for a wildlife course at Utah State University, with most of our studies directed toward mule deer. I hurriedly reported my find to our professor. Elk were scarce in the forest, and up to that point none of us students had seen one.

Our professor examined the track, confirmed that it was indeed an elk’s and commented on how fortunate we were to have seen it. Though we worked in the forest the rest of the summer, we never laid eyes on a single elk. My old professor is gone now, but the elk aren’t.

In fact, they’re present in such large numbers throughout the West that they are using up the range almost as fast as it can grow.

As hunters, we’re familiar with wildlife success stories in terms of the enormous increases in animals today compared to their numbers at the turn of the century. Whitetails have made unbelievable gains, and so have muleys, antelope, turkeys and other species. But elk have an intriguing story that’s different from other game.

When America was settled, elk ranged from the East to the West Coast. Six subspecies lived in North America, roaming in eastern hardwood forests, across the central plains and in the western mountains. It didn’t take very long, however, for elk to be driven to extinction in many areas. The Eastern elk disappeared before the turn of the century, the Merriam’s around 1904. Other subspecies were dwindling rapidly. By 1910, it appeared that elk were headed for extinction. Around 1920, the major species, the Rocky Mountain elk, numbered fewer than 50,000 animals, most of them in Yellowstone Park and the National Elk Refuge in Wyoming. On top of their superb-tasting flesh and the fact that they competed with livestock for range grass, it was their tusks or ivories that also contributed to their downfall. Bulls and cows alike have a pair of unique teeth that are highly prized for jewelry. Historical accounts state that untold numbers of elk were killed exclusively for their teeth.

Then began the unique aspect of the elk success story. From 1892 to 1939, about 5,200 elk were transplanted via rail, wagon and trucks to 36 states and several Canadian provinces from Yellowstone Park and the National Elk Refuge. An all-out effort involving thousands of people was made to bring elk back to North America. Today, according to the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, there are approximately 960,000 elk in the U.S. and Canada. The 1 million mark is just around the corner. A range map of the transplant efforts resembles a huge wheel, with spokes emanating from the Wyoming hub.

Why have elk made such dramatic increases? A combination of factors created population booms. Forest fires and logging benefitted elk by producing the kind of forage preferred by the animals. More restrictive seasons and hunts protected female elk, encouraging herd expansion. Increased transplant programs that continue to this day allow elk to reestablish themselves in habitats where they once flourished.

This enormous success story has not come about painlessly. In the viewpoint of some (but not all) cattlemen, every bite of grass taken by an elk is one less bite for a cow.

Efforts by state agencies to introduce elk were commonly opposed not only by ranchers, but also by the U.S. Forest Service and U.S. Bureau of Land Management–two federal agencies that control almost 500 million acres in America.

What did the feds have against elk? As guardians of public lands, both agencies are mandated to manage lands under a multiple-use system. Unfortunately, multiple-use seldom favors all uses but ranks them in order of priority. Until recently, livestock grazing was a far higher priority than wildlife management. I recall attending many so-called “intergency” meetings in Utah when I worked as a wilife biologist. The Forest Service consistently gave in to ranchers’ demands and allowed cow elk hunting on ranges that had the potential of supporting many more elk. As a result, elk herds were maintained at low levels. On some Utah national forests, federal officials were so closely aligned with cattlemen that forest rangers wouldn’t allow elk to be transplanted into their districts because it was all “allotted” to cattle. For many years there were zero elk in those forests, but happily those days are over.

According to Mike Welch, big-game coordinator for the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, elk are flourishing in that state. “We have about 60,000 elk in Utah,” Welch says. “They occupy practically all of their historic habitat and are at their highest levels since being reintroduced from Wyoming about 80 years ago.”

As a longtime resident of Utah, I watched those herds grow enormously from the day I spotted that strange track as a college student in the early ’60s. In 1970, 14,000 elk lived in Utah. In just over 25 years, 46,000 more joined their ranks. So many more, in fact, that last year the state allowed hunters to take two elk, one of which had to be antlerless. In 1997, Wyoming also allowed an extra antlerless elk to be taken. Never in modern history has a state allowed more than one elk to be killed by an individual hunter. Obviously, elk are doing too well in some areas, and efforts are being taken to trim their numbers.

More big news for elk hunters comes from Colorado, the number-one hunting state in terms of herd numbers, hunter harvest and numbers of elk hunters. This fall, hunters will be allowed to purchase either-sex elk licenses across the counter for the general season in 48 units.

“The elk population in some areas of the state is higher than the habitat can sustain,” says state terrestrial wildlife manager Jim Lipscomb. Another Colorado wildlife officer, Jim Olterman, is optimistic about the upcoming 1998 hunt. “If the weather is at all decent,” he says, “I wouldn’t be surprised if we set another record for elk harvest.” The highest harvest record in Colorado was a whopping 51,595 elk taken in 1990. No other state has ever come close to that figure. Some observers believe that the general either-sex hunts this fall may result in an incredible harvest of 60,000 elk.

Arizona and New Mexico also show amazing statistics regarding elk herds and harvests. In 1975, Arizona hunters took about 1,100 elk; in 1995, more than 10,000 were killed. New Mexico hunters shot 1,800 elk in 1975 and more than 12,000 in 1995. Nevada had zero elk in 1975; the state now has a growing herd of more than 3,500 animals. California’s tule elk herd has grown from 600 in 1975 to more than 3,000. Despite animal-rights protests, tule elk hunts have been held in California for the last six years.

Of the western elk states, only Washington shows declining elk harvests. This is the smallest state in the West, but it has the second-highest human population, other than California. There seems to be little hope for Washington, with enormous urban growth predicted for years to come. Too many people and rapidly dwindling habitat seem to be taking their toll in that state. According to wildlife officers, more than 30,000 acres each year are lost to development and human encroachment.

Elk are also doing well in states outside the West. Herds are increasing dramatically, and in some states brand-new herds have been recently established. Arkansas is one of the hot success stories. With no elk in 1975, the state now has a population of almost 500. Arkansas will have its first elk hunt ever this fall. South Dakota’s elk are in great shape, increasing from zero in 1975 to almost 4,000 today. In 1995, 25 elk were introduced into Wisconsin. Those elk are doing remarkably well and are expected to expand their numbers appreciably. Many other states are reporting expanding elk herds. Canada’s elk herds have grown rapidly, increasing from 40,000 in 1975 to 89,000 in 1995. With this wonderful success story, you’d think that elk hunting would be easier than ever. That’s wishful thinking. Averaging hunter success in all the western states, elk hunters continue to have only a 20 to 25 percent success rate.

There’s a logical reason for that. Though there are more elk, they continue to live in the most rugged landscape in the Lower 48. The mountains remain as steep as ever, and the forests are still there–presenting the same formidable obstacles. Elk hunting will always be a physical challenge in much of the West.

Hunting strategies themselves have changed radically over the last few decades. I remember making my own homemade bugle calls out of a chunk of garden hose, a length of pipe or a willow branch. Granted, the sound that emanated from these devices was tinny and quite unlike the bugle of a live elk, but it worked. Then came the diaphragm call, which added an amazing new dimension to elk hunting. In reality, the call was first used for turkey hunting, and it’s commonly believed that callmaker Wayne Carlton was the first to modify the sound to imitate an elk. Dozens of diaphragm models are on the market these days, used with or without a grunt tube.

The next big discovery to hit the hunt scene was when Montana hunter Don Laubach realized that imitating a cow elk’s chirp could have a profound implication in hunting strategies. Laubach gave me one of his prototype calls in the early 1980s and asked me to experiment with it. I did, was immediately impressed with the results and wrote the first story ever on cow calling (“Elk Hunting’s Newest Secret,” September 1986). Now, cow calling is routine, and more than a dozen manufacturers make cow calls.

Not everyone is happy with the elk success story; the big animals cause serious damage to the ranching and farming industry. In places where elk have overpopulated, starvation may occur when forage is depleted. Game departments minimize these impacts by issuing antlerless tags to keep elk in check with the carrying capacity of the range.

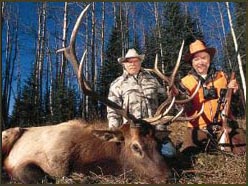

I’m one of the many happy hunters who have no problem with taking a cow elk here and there. I’m also more than pleased if I’m fortunate enough to tie my tag to a bull. As the old saying goes, any elk is a good elk. And you might say that the good old days are not gone forever. When it comes to elk hunting, they’re here right now. ciably. Many other states are reporting expanding elk herds. Canada’s elk herds have grown rapidly, increasing from 40,000 in 1975 to 89,000 in 1995. With this wonderful success story, you’d think that elk hunting would be easier than ever. That’s wishful thinking. Averaging hunter success in all the western states, elk hunters continue to have only a 20 to 25 percent success rate.

There’s a logical reason for that. Though there are more elk, they continue to live in the most rugged landscape in the Lower 48. The mountains remain as steep as ever, and the forests are still there–presenting the same formidable obstacles. Elk hunting will always be a physical challenge in much of the West.

Hunting strategies themselves have changed radically over the last few decades. I remember making my own homemade bugle calls out of a chunk of garden hose, a length of pipe or a willow branch. Granted, the sound that emanated from these devices was tinny and quite unlike the bugle of a live elk, but it worked. Then came the diaphragm call, which added an amazing new dimension to elk hunting. In reality, the call was first used for turkey hunting, and it’s commonly believed that callmaker Wayne Carlton was the first to modify the sound to imitate an elk. Dozens of diaphragm models are on the market these days, used with or without a grunt tube.

The next big discovery to hit the hunt scene was when Montana hunter Don Laubach realized that imitating a cow elk’s chirp could have a profound implication in hunting strategies. Laubach gave me one of his prototype calls in the early 1980s and asked me to experiment with it. I did, was immediately impressed with the results and wrote the first story ever on cow calling (“Elk Hunting’s Newest Secret,” September 1986). Now, cow calling is routine, and more than a dozen manufacturers make cow calls.

Not everyone is happy with the elk success story; the big animals cause serious damage to the ranching and farming industry. In places where elk have overpopulated, starvation may occur when forage is depleted. Game departments minimize these impacts by issuing antlerless tags to keep elk in check with the carrying capacity of the range.

I’m one of the many happy hunters who have no problem with taking a cow elk here and there. I’m also more than pleased if I’m fortunate enough to tie my tag to a bull. As the old saying goes, any elk is a good elk. And you might say that the good old days are not gone forever. When it comes to elk hunting, they’re here right now.