We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

Admittedly, one of the most overdone topics in the hunting industry is the Best Whitetail Cartridge. Every outdoor publication and website has done it. Some several times. A few annually. And still, no one agrees.

Why? Because the question is too broad. As if every whitetail weighed 300 pounds and lived on the edge of Saskatchewan’s buffalo plains where 300 yards is considered close. Or 100 pounds and haunted South Carolina swamps where 75 yards is considered a long shot.

Nevertheless, the articles keep popping up. That’s not all bad, because it gets hunters arguing and discussing stuff, if not thinking, and at least sharing some ideas. A few generate a hint of light with all their heat.

This article will avoid describing the Best Whitetail Cartridge in favor of comparing three of the more famous. Surely thousands, if not millions of deer hunters, consider one of these the ultimate whitetail round, whether it is or isn’t. So let’s dive right in.

.30-30 Winchester

This famous, old, rimmed cartridge is often credited for having sent more deer to the dinner table than any other. How anyone can prove or disprove this makes it moot. The point is this: Since 1895 the .30-30 Winchester has been one widely used and beloved whitetail cartridge. But its fame may be due more to the rifles in which it’s most often chambered than to its ballistic performance.

At its heart, the .30-30 is a middle-of-the-road round. Not too big, not too small. It’s not too fast, not to slow. The round burns about 32-grains of powder to throw 150-grain to 170-grain flat-nosed bullets. These drop deer reliably and, “you can eat right up to the hole.” To the degree this is true we credit the little rimmed cartridge’s mild muzzle velocity. Depending on barrel length, give it 2,200 to 2,300 fps with a 170-grain slug, about 2,300 to 2,450 fps with a 150-grain. That’s 400 to 700 fps slower than most other standard deer rounds like .243 Win., .308 Win., and .280 Rem.

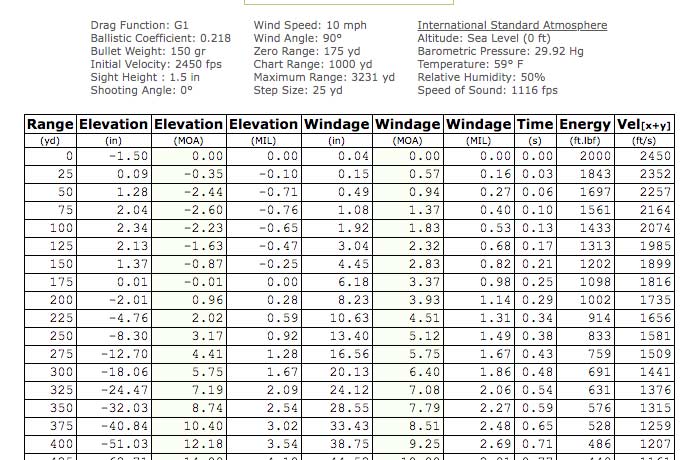

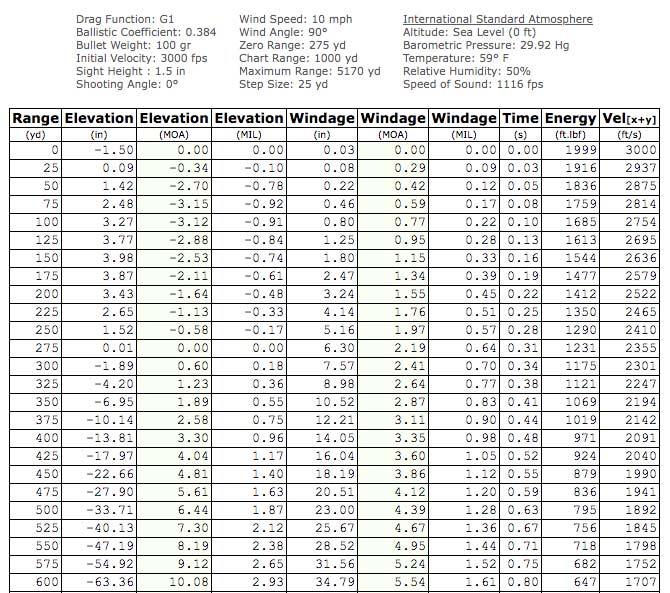

Contrary to conventional assumption, the .30-30 does not produce crushing levels of kinetic energy. At the muzzle, those 150-grain slugs might be packing about 2,000 ft-lbs. A .30-06 pushing the same bullet would produce closer to 3,000 ft-lbs. Even the little .243 Winchester throwing a 100-grain bullet 3,100 fps cranks out more muzzle energy—2,100 ft-lbs—than the .30-30. And it retains more of it downrange. At 200 yards, the 30-30 bullet’s energy has dropped to about 1,000 ft-lbs. The 243’s is still 1,500 ft-lbs.

How can a 100-grain bullet “hit harder” than a 150-grain? Velocity and something called Ballistic Coefficient (B.C.). Double a bullet’s mass and you double its energy. Double its velocity and you quadruple its energy. As for Ballistic Coefficient, that’s a fancy way of measuring a bullet’s ability to resist air drag. Like an Indy car versus a Mac truck. A long, slim, sharply pointed, boat-tailed bullet will slip through the atmosphere with minimum drag while a shorter, flat-nosed bullet with a flat base exposes more surface to air friction. It wastes its energy pushing air.

This combination of muzzle velocity and B.C. determines the .30-30’s trajectory. Zero a 150-grain .30-30 flat-nose dead-on at 175 yards, and it will peak 2.6 inches above line-of-sight at 75 yards and not fall more than 4 inches below line-of-sight until 220 yards. That just happens to be the range at which most of us engage whitetails. Maybe not most buffalo plains western hunters, but certainly woods, swamps, brush, and mixed farmland hunters from south Texas to Minnesota, Florida to Maine.

But the question remains: Why settle for this limited range when so many more modern cartridges can easily shoot that flat or flatter to 300, 350, even 400 yards? And the answer in large part is John Moses Browning. This is the 19th-century gun design genius who created the Model 94 Winchester, the first rifle chambered for the .30-30. Thanks to Browning’s dual-bolt locking bars, the M94 is strong enough to contain the higher pressures created by the then-new smokeless powders used in the .30-30. Winchester’s M94 and Marlin’s lever-action rifles became America’s favorite deer rifles and remained that deep into the 20th century. Heck, they may still be. Slim, nicely balanced, fast to the shoulder, mild recoil (about 11.5 ft-lbs at 10 fps with a 150-grain bullet in 7.5-pound rifle), and fast to cycle. Flicking that lever will run five rounds from the tubular magazine through the action and down the barrel as fast as a running buck could flash through gaps in the trees.

Speaking of tubular magazines, these handy cartridge storage containers are part of the reason the .30-30 Win. is a ballistic flop. A launch speed of just 2,300 fps doesn’t help much, but it’s the flat-nosed and round-nosed bullets that really sacrifice speed and energy downrange. So why not load pointy, higher B.C. bullets? Because a sharp tip behind the primer of the stacked round in front can ignite it, setting off a deadly chain reaction.

Read Next: The State of the Deer Rifle

Hornady’s rubber-tipped MonoFlex bullets are sharp-tipped without fear of primer detonation. The Hornady MonoFlex 140-grain, boat-tail bullet for the .30-30 Win. boasts a B.C. of .277. Compare that to the 150-grain Round Nose with B.C. of .186. Drive both at a top-end muzzle velocity of 2,400 fps and you get slightly less drop and drift with the MonoFlex.

The .30-30 is a ballistic ho-hum yawner, but in a slick lever-action rifle it’s a deer killing dream machine in heavy cover.

.243 Winchester

Since we’ve already introduced this pipsqueak, let’s flesh it out. This short-action .24-caliber is a .308 Winchester case necked down to hold that smaller bullet. When it hit the streets in 1955, it took whitetail hunting by storm. At the time, one of the most popular, light-recoiling deer rounds was the excellent .257 Roberts. The .250-3000 Savage was going strong, too. This .243 Winchester shot similar weight bullets at similar velocities, but the .243-inch diameter was just enough narrower than the .257 to increase B.C. and improve downrange ballistics slightly. Besides, all the gun scribes were bloviating about this wonderful new .24-caliber, combination deer/varmint/predator round, so everyone had to try it.

Well, it’s stood the test of time. The excellent .257 Roberts has faded, but the .243 Winchester is a standard—chambered by just about everyone who builds hunting rifles. It’s available in bolt-actions, levers, pumps, autos, and single shots. It wouldn’t surprise me if someone chambered it in a blowgun. A 100-grain bullet might sound a bit light to many, but as already noted above, making it aerodynamically efficient, and driving it 3,000 to 3,100 fps, ensures it hits harder than the 150-grain .30-30. And reaches a lot farther with similarly mild recoil. Figure about 12.8 ft-lbs at 10.5 fps. Pussy cat territory.

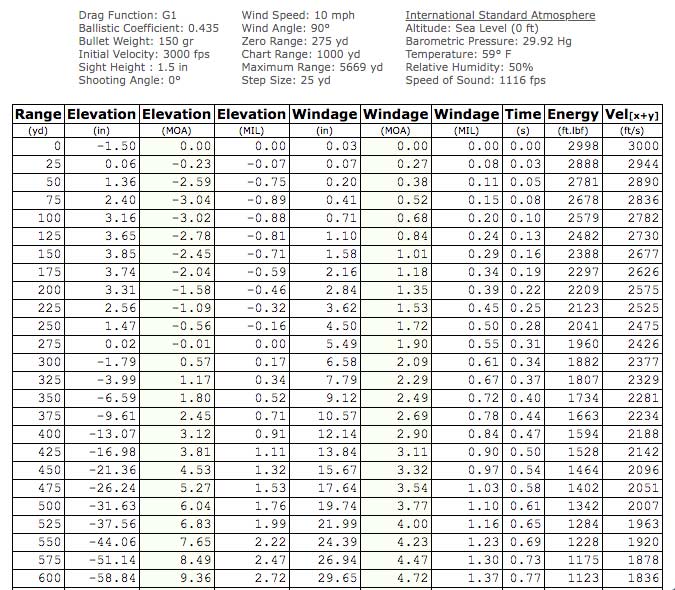

The trajectory table here tells the tale. The only other thing to highlight is the potential for getting it in light, quick-handling rifles. Unlike the .30-30, the .243 Win. has never been closely identified with a specific rifle style. It is most common in bolt-actions, but those could be anything from long actions with big, heavy stocks and 26-inch barrels weighing 8 to 9 pounds to trim, light, quick little short actions with 18.5-inch barrels at less than 6 pounds. I’ve discovered a trim short action with a 22-inch barrel weighing about 6 pounds before scope mounting makes for a fine deer hunting rifle. It’s lively and quick enough for woods shooting and steady with enough reach for open country hunting. With light rifles like this in .243 Win., I’ve routinely laid out whitetails as heavy as 250 pounds and as far away as 375 yards.

One complaint you’ll hear is that the 100-grain .243 bullet hasn’t enough mass and momentum for reliable penetration. Unless the bullet is a monolithic or fairly hard, tough, controlled-expansion number, it probably will not shoot through. This is not the best option for laying down a blood trail. Lung/heart struck deer often race for several seconds before tipping over. Shoot open fields or hone your tracking skills.

These light bullets are also not going to plow through thickets like a bull moose. Small branches and even some tough grasses can deflect them off target. But take this with a grain of salt: Most other bullets are similarly deflected. This flies in the face of the widely held belief that the .30-30 is a brush buster. I have my doubts. Most brush-busting tests have concluded that .30-30 slugs, too, are easily bent into new angels of flight from relatively light brush. Wise hunters simply avoid brush shots. Better to pick an opening. If you really want a brush busting round for whitetails, try a 500-grain solid in a .470 Nitro Express.

.30-06 Springfield

I tried to avoid this, but I just couldn’t. The .30-06 Springfield has been the standard for too long and may have terminated as many deer as the old .30-30. It’s not cool to advocate for the 113-year-old .30-06 WWI military round these days, but this antiquated warhorse can still make hay—whether the sun is shining or not—because it shoots the same .308-inch diameter bullets as the .30-30, but with about twice the quantity of powder and 18,000 psi more allowable pressure. Muzzle velocity isn’t everything, but 3,000 fps is significantly faster than 2,400 fps. Add the higher B.C. of a typical spire point boat tail (about .435), and you increase reach and on-target energy dramatically. Whitetails don’t like it, but millions of hunters do.

The .30-06 case shape accounts for this. It sprang from the old 7x57mm Mauser. Both share the same rim and head diameters and basic body size. The .30-06 case just stretches 2.484-inches from base to neck while the 7mm Mauser is limited to 2.235-inches.

The .30-06 was such a trendsetter in the gun world that it inspired a common action length known as the long-action, standard-length, and .30-06-length action. This is the action length used for the .270 Win., .280 Rem., .25-06 Rem., .6.5-06, .338-06, .35 Whelen, 7mm Rem. Mag., .300 Win. Mag., .338 Win. Mag., and even the .458 Win. Mag., among others. Whew!

Oddly enough, this standard-length action is now used to knock the .30-06. Somehow shooters have gotten the idea there is something magical about short-action cartridges, which are themselves offshoots of the .30-06.

The trendsetter, short-action cartridge is the .308 Winchester at 2.015-inches case length. It came along in 1953, the same year Stalin died in Russia, Dwight Eisenhower was inaugurated president of the U.S., and “Your Cheatin’ Heart” by some guy named Hank Williams was playing on radios and jukeboxes across America.

Based on the .300 Savage, the .308 Win. oddly shares the same rim and head sizes as the—you guessed it—.30-06. This is why some smart alecks call it the 30-06 Short. It had a slow start, but after militaries adopted it as the 7.62x51mm NATO, it started gathering steam. It soon became the standard parent case for today’s widely known short-action cartridges like our little .243 Winchester.

Read Next: Our 4 Favorite Deer Hunting Guns of All Time

What too many hunters have bought into is this idea that a 1/2-inch shorter action will make a hunting rifle appreciably lighter, stiffer, more accurate, and faster to cycle. This might shave 4-ounces of rifle mass and 0.001-inch off a 10-shot benchrest group. I fail to see where 0.001-inch better accuracy can make the difference between “break out the skinning knife” and “turn loose the tracking dogs.”

What the .308 Win. does do differently from the .30-06 that matters is 100 to 200 fps less velocity. Deer don’t notice this, but if you’re looking for optimum flat trajectory and minimal wind deflection, it could matter to you.

Another advantage the .30-06 provides is an incredible variety of bullet sizes. Handloaders can work with 100-grain plinkers all the way up to 220-grain round-nose thumpers. Factory loads start at about 125-grains and climb right up to 220. The heavier slugs travel slower, but they carry a lot of momentum that seems to drive them right on through. If you like a big leak for blood trailing, the .30-06 with heavy, tough bullets will give you one. Light cup-and-core bullets don’t always exit or tear an appreciable entry hole.

For many, the downside to the .30-06 is recoil. In a 7.5-pound rifle, it’ll run about 23.8 ft-lbs at 14.3 fps with a 150-grain bullet, 27.3 ft-lbs at 15.3 fps with a 180-grain, and 30.3 ft-lbs at 16 fps pushing a 220-grain slug.

If that sounds like more shoulder stimulation than you’d welcome, you may want to step down to the .308 Win., which can easily make a claim for the ideal whitetail cartridge. But then so can the 7mm-08 Rem., .260 Rem., .270 Win., .280 Rem… and especially the .30-30 Win. and .243 Win.

Read Next: Best Deer Hunting Calibers