You probably rejoice when you spend an entire day afield without bumping into another hunter. Encountering strangers—especially when they’ve stumbled across your secret spot—spoils the solitude we seek in the outdoors.

So you’d be hard-pressed to find any sportsman or -woman who wants more competition in the woods. Yet, more hunters is precisely what we need right now.

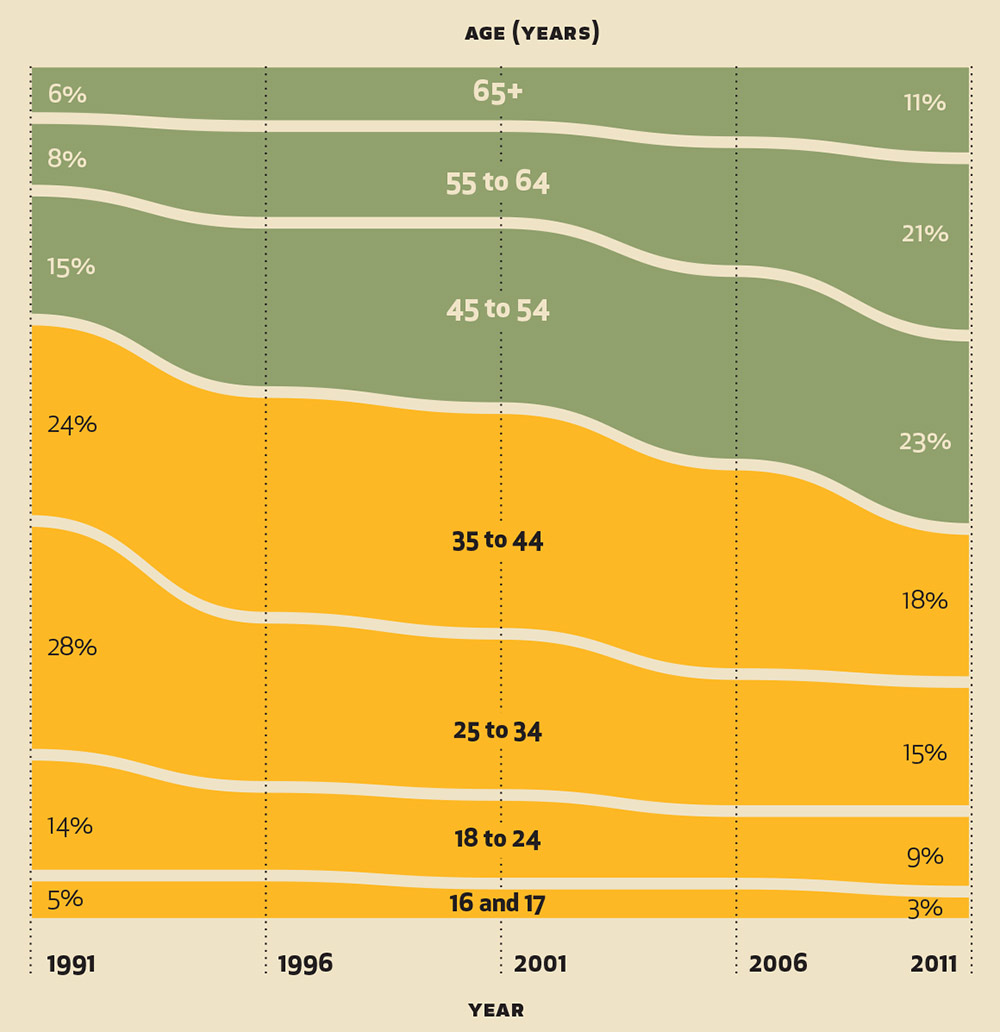

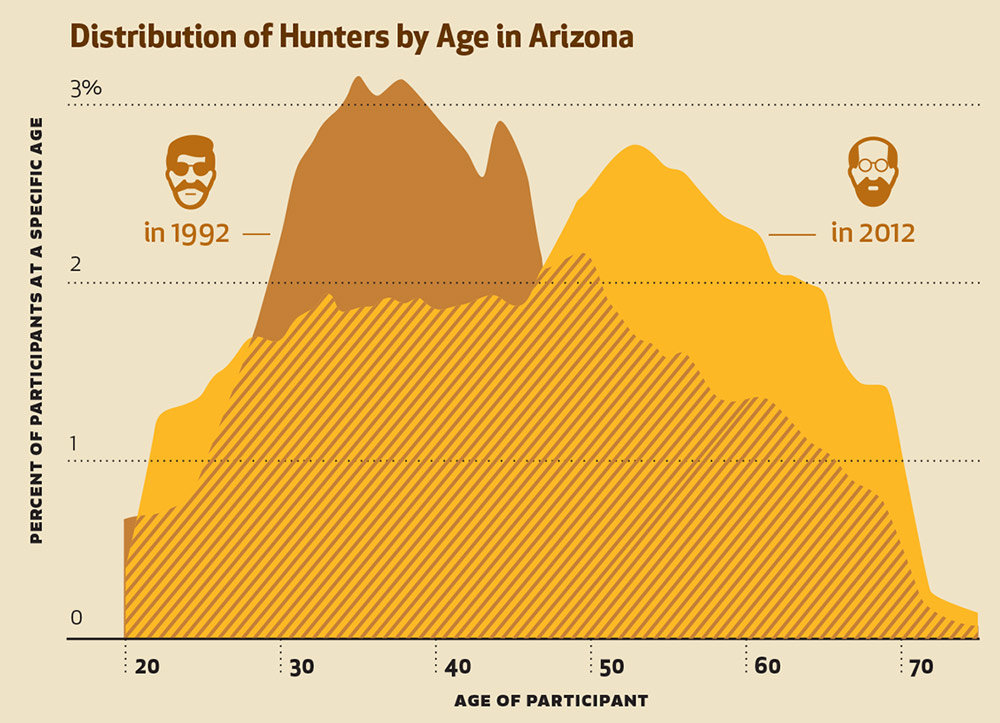

Here’s why: Baby boomers make up our nation’s largest cohort of hunters, and they’ve already begun to age out of the sport. Within 15 years, most will stop buying licenses entirely. And when they do, our ranks could plunge by 30 percent—along with critical funding for wildlife management, advocacy for hunting, and a tradition that’s probably pretty important to you. In other words, the clock is ticking. And unless we act now, we might not recover from the fallout.

Baby Blues

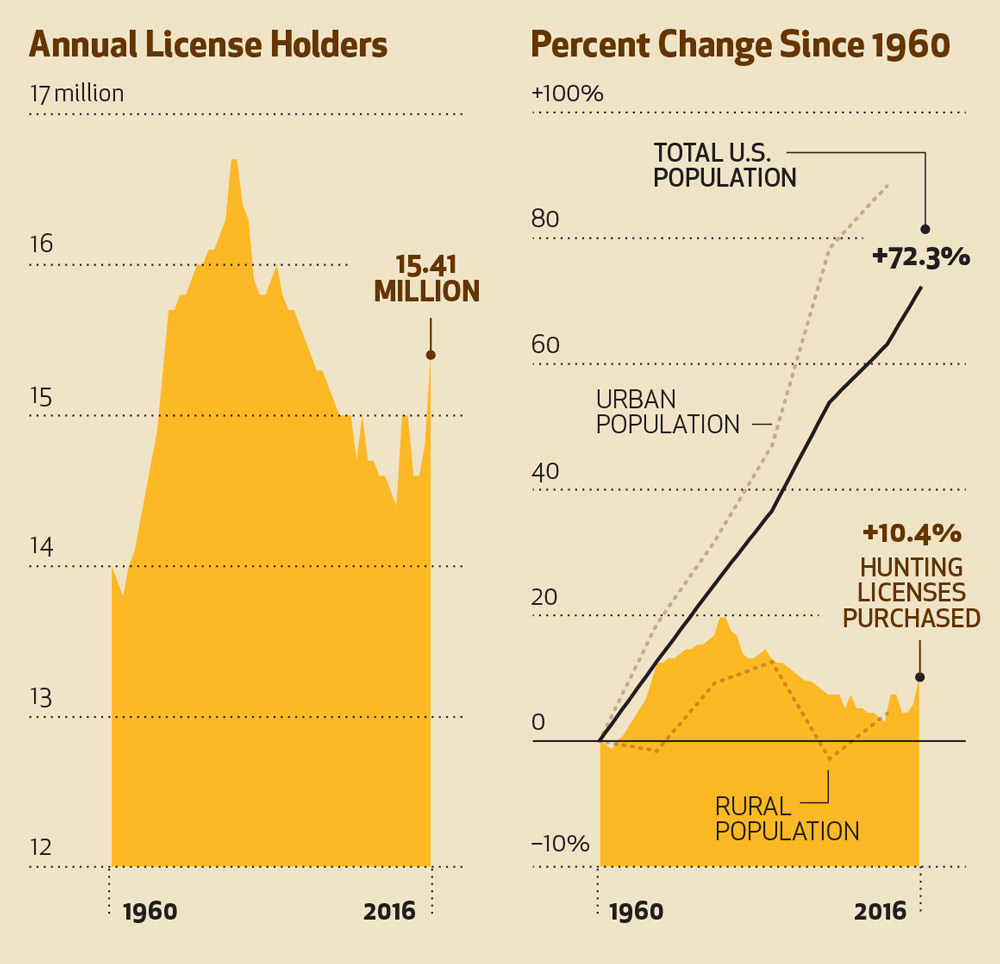

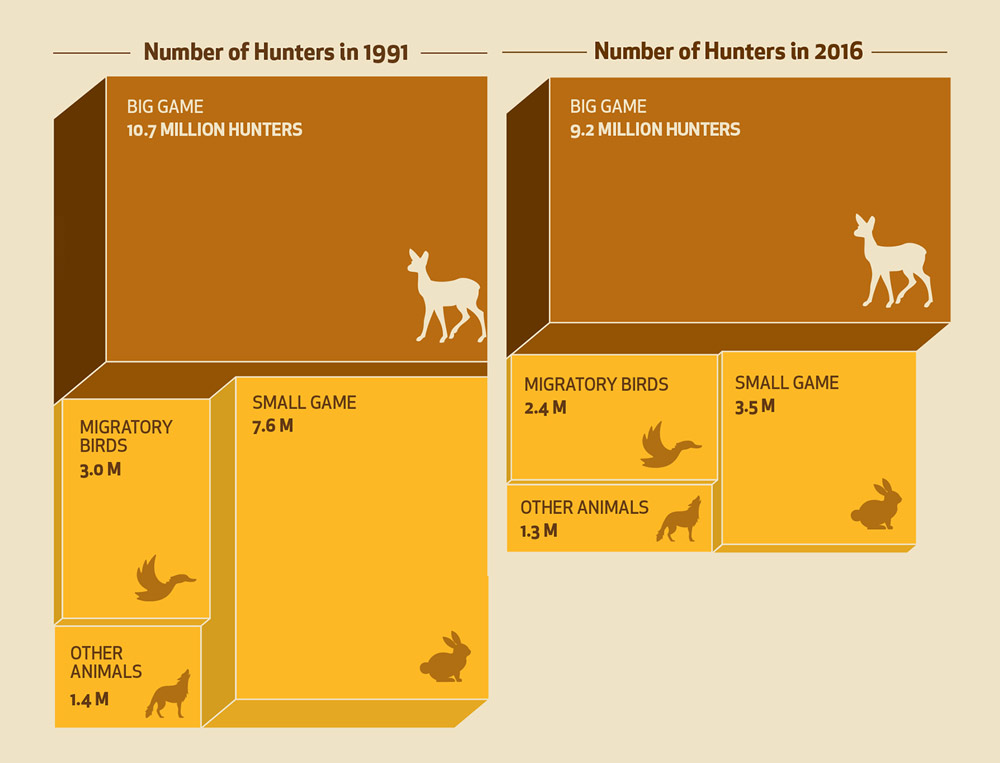

Hunting participation peaked in 1982, when nearly 17 million hunters purchased 28.3 million licenses. Hunter numbers have steadily declined since. We lost 2.2 million hunters between 2011 and 2016 alone, according to the National Survey of Hunting, Fishing, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation, a report issued by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. In 2016, just 11.5 million people hunted. That’s less than 4 percent of the national population.

Baby boomers (anyone born between 1946 and 1964) make up roughly a third of all hunters nationally. They currently range from 54 to 72 years old, which means the oldest have already crossed the threshold for aging out.

“If you watch the demographic shift of license purchases by age, what you find is that when people hit their late 60s and early 70s, regardless of how much you incentivize them, they stop hunting and fishing,” says Matt Dunfee, director of special programs at the Wildlife Management Institute (WMI). He’s been studying hunter recruitment and retention for the last decade. “There’s nothing we can do. They just get too old.”

Fishing participation is also in danger of imploding, but that collapse won’t occur for about 20 years. If we can defuse the more pressing hunting license problem first, we can apply those solutions to fishing.

Participation Plummets

The baby boomer bubble is going to burst, but boomers aren’t entirely to blame for this mess. Hunters should have been recruiting enough new license buyers to, if not increase ranks, keep them stable. So what gives?

Shifting demographics play a big part. Hunters have historically been white men; today, more than 90 percent of hunters are Caucasian, and more than 70 percent are male. But soon—by 2044, according to U.S. Census projections—Caucasians will make up less than half the U.S. population. Plus, the rural population is staying relatively stable, while urban populations are increasing.

“If we think about the future of hunting like a portfolio, right now we have everything invested in one stock—in one demographic: middle-aged white guys. How representative is that of the American culture right now? More importantly, how representative will it be in 50 years?” Dunfee says. “And the crazy thing is, we know this stock is going to go down. Let’s diversify the portfolio so hunting becomes something Americans do, not just something middle Americans do.”

Band-Aid Programs, Big Problems

This might be news to you, but wildlife agencies and non-governmental agencies (NGOs) have been aware of the issue for years. States initially reacted by offering new-hunter events that recruitment, retention, and reactivation (R3) experts call “feel-good programs.”

In 2009, researchers at the WMI found that nearly 500 of these programs were in place nationwide: Multiple programs for attracting new hunters existed in the same states, most of them duplicating efforts and few gathering data. Only a quarter kept track of who attended, and just 10 percent administered exit surveys to determine whether their program was effective. But the continued decline of license sales demonstrates this glut of good intentions didn’t stop the countdown clock.

“Most often, we are preaching to the choir. We’re giving the kids of folks who already hunt [about 80 percent of attendees] this opportunity, rather than reaching new audiences,” says Chris Willard, R3 coordinator at the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Meanwhile, these programs aren’t that strong at attracting a diverse crowd, according to the Council for Advancing Hunting and the Shooting Sports (CAHSS). Many events are designed for kids, which often deters adults from enrolling. And, contrary to popular belief, kids aren’t the best audience to recruit as lifetime hunters. In fact, they’re actually the hardest to retain. This may surprise hunters from hunting families, but think about R3 in the context of non-hunting families: Kids don’t have disposable income, parents direct their time, and competing interests like athletics only intensify with age.

“If you spend $500 on a kid, the probability you get a return on that investment is really low,” Dunfee explains. “But a young adult population from college students on up has time, has money, has solidified socially, has motivation. We’ve seen with pilot efforts that this audience can be motivated at a much higher rate. Your return on investment is much higher, because they’ll buy a license next year, and they’ll take their friends.”

R3 stakeholders (who usually belong to the outdoor industry, state wildlife agencies, or conservation NGOs) also realized too late that recruitment takes time.

“It’s not enough to just host these events and have a good time—you have to be really strategic about who you bring into those events,” Willard says. “And more importantly, once they’re at those events, how do you connect them to that next step?”

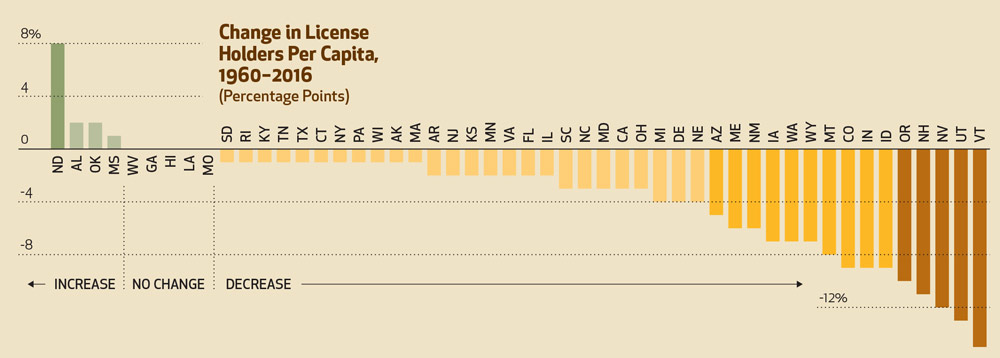

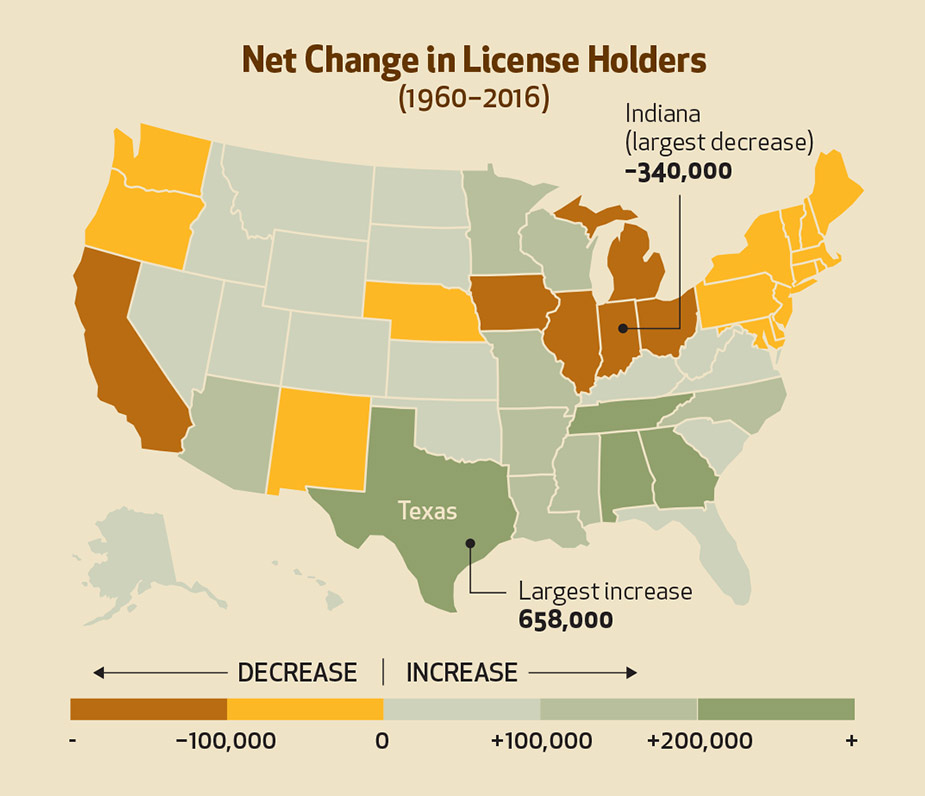

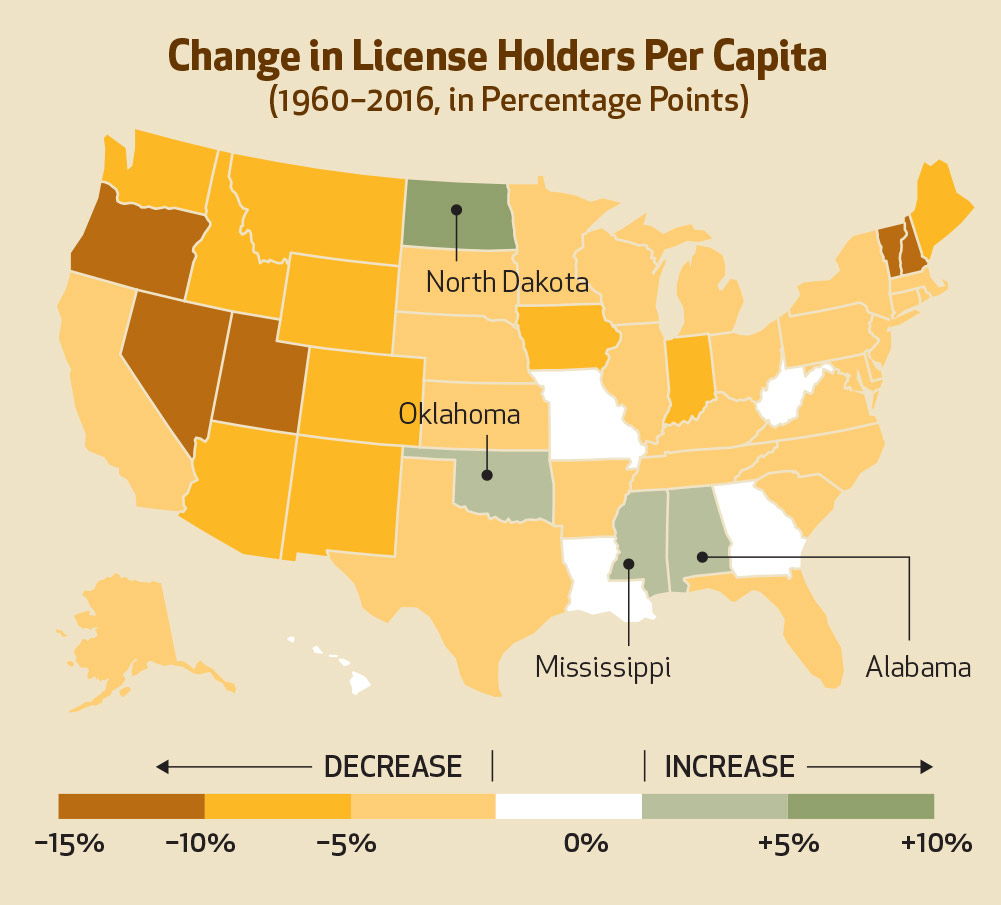

Hunting License Holders, by State

We broke down historical hunting license data by state and found the net change in hunting license sales has decreased in 21 states and increased in 29 states since 1960 (“Net Change,” below). But that analysis is deceiving until you track it against population changes (“Per Capita,” below). Only four states have seen a per capita increase in hunting license holders (ND, AL, OK, MS). The remaining states have seen no change or a decrease in holders.

Rethinking Recruitment

So what is effective? Workshops, like those offered by the Becoming an Outdoors Woman programs, get more of the folks who enroll to buy hunting licenses.

“We know that model works,” Willard says. “The challenge has been, most agencies do a handful of those programs in their state every year. And that’s not enough to really move the needle. It’s not scalable. So what we’re working on is to take that model that works, and scale it.”

Other agencies are testing programs designed to target the locavore movement that has captivated urbanites.

“Hipsters want to hunt. But they don’t want to hunt the way a rural farm boy from Illinois wants to hunt,” Dunfee says. “They don’t want to dress the same way, they don’t like focusing on antlers, they don’t like taking pictures of their animals. But they want local, sustainable, ecologically conscious meat. And within our efforts, there are few places to realize those values.”

Charles Evans, an R3 coordinator in Athens, Ga., piloted the Field to Fork program in 2016 with groups like the Quality Deer Management Association. Evans recruits at farmers markets by offering samples of venison.

“We recruit people, including vegetarians, vegans, organic farmers, nutritionists—we’ve had all sorts of different people come through our course, and they’re all there because they want to learn to hunt,” says Evans, who is working to expand the program statewide. “They likely already have an interest in nature. They see hunting as viable, especially when you give them the facts about how hunting supports conservation. And their willingness to learn how to do it is astounding. We were met with more demand than we could handle.”

Meanwhile, Mountain Song Expeditions in Vermont offers weekend intensives for novice deer hunters, and eight-month apprenticeships. Course activities include traditional shooting practice and blood-trailing exercises, but also mock hunts, meditation, and a sacred goat slaughter so students can practice butchering.

“Most people who learn to hunt are woven into communities who give them that momentum. The type of people I teach don’t know anyone else who hunts,” says owner Murphy Robinson, a 35-year-old former vegetarian. “They aren’t friends with people that hunt who are going to reinforce that. So we’re creating that group within this program.”

Robinson is also a hunter-safety instructor. Hunter-ed courses are limited in their R3 role since they’re designed to address safety and game laws, not mentorship. Research shows hunter ed isn’t a barrier to R3, but state agencies are making courses more convenient by addressing issues like seasonal bottlenecks.

“Our common refrain was, ‘You should’ve planned better, it’s not our fault,’” Willard says. “But if we know people are clamoring for hunter-education classes in September, they’re clamoring because they really want to hunt. And if we don’t accommodate that, we’re not going to be able to sell them a license.”

Another R3 champion is Dr. Loren Chase of the Oregon DFW. One of his reports shows small-game camps recruit hunters just as effectively as big-game camps. Chase argues that small-game hunting is cheaper and easier. It can be done more frequently, offers more trigger pulls, and takes less biomass out of the ecosystem.

An Easy Cure

Right now, organizations are in the trenches. Even the job of R3 coordinator is relatively new—26 states have R3 coordinators, compared to just seven states two years ago, reports CAHSS. The other party responsible for our situation is the orange army. Agencies aren’t charged with recruiting hunters, but they’re stepping up because they must. Hunters need to step up, too. There are piles of research to wade through, but the takeaway is stupidly simple: If just 30 percent of the 11.5 million individuals who hunted in 2016 create one new hunter, we could solve the looming license problem in one year.

There’s a catch, of course—two, actually. The first is that recruiting a hunter takes time. Veterans should budget two to four years for mentoring a newbie. Hunters must commit to ensuring rookies get the skills and support they need to become an annual license buyer.

The second, Dunfee says, is to recruit someone who doesn’t look or live like you. If you’re a man, maybe it means recruiting a woman. If you’re white, maybe it means mentoring a person of color. If you’re a farmer, maybe it means teaching a townie. Choose your own apprentice—after all, it should be someone you like to spend time with—but remember to be on the lookout for aspiring hunters in all sorts of unexpected places.

“We could shift the paradigm. Hunters were given a gift of the resources of North America and the opportunity to hunt,” Dunfee says. “And implicit in that gift is that it must be passed on to somebody else.”

3 Recruitment Programs That Are Worth Trying

There’s no shortage of hunter recruitment programs out there. The problem is, many of them don’t actually create new hunters. These feel-good programs often consist of single-day or weekend events that attract interested newbies (or children of existing hunters who are going to learn to hunt anyway) without providing the long-term mentoring they need to feel confident in the field. The organizers of such events might feel like they’ve accomplished something, but if the participants don’t purchase hunting licenses, these recruitment events are falling well short of their intended goals.

Fortunately, researchers and recruiters have learned what actually works when it comes to attracting—and retaining—new hunters. More and more programs that prioritize long-term mentoring are gaining momentum. Here’s a look at a few organizations that are following the recommendations for successful recruitment, and that are worth recommending to anyone looking to start hunting.

1. QDMA Field to Fork

Originally founded in 2016 at the organization’s headquarters in Athens, Georgia, he Field-to-Fork harnessed the enthusiasm of the locavore movement.

Originally founded in 2016 in Georgia, the Field-to-Fork program harnessed the enthusiasm of the locavore movement. The pilot program attracted curious farmer-market attendees with venison, then introduced them to the next logical step in that food chain: hunting. The season-long program—which includes classroom sessions, field days, hunts, and meat care lessons—is proving so successful that QDMA has expanded it to 13 total states. Those currently include Alaska, Florida, Georgia, Iowa, Michigan, Missouri, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, Vermont, and Wisconsin. The program has a strong track record of retaining folks after the first season: Of the 22 adult participants in the pilot class, 80 percent continued to hunt on their own within the first year. You can learn more about the Field-to-Fork program here.

2. Minnesota’s Adult Learn-to-Hunt Whitetail Deer Program

Much like the Field-to-Fork program, this offering from the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources pairs hunter hopefuls with prospective mentors. Instead of following them for one, season, however, the mentor-mentee relationship is designed to expand over three seasons (as experts recommend). The first year consists of an introduction to the sport and one-on-one hunting, the second incorporates more off-season involvement through scouting and shooting, and the third allows hunters to test their skills by hunting solo, but still within the supportive environment of a collective deer camp.

If you’re interested in what one hunter and mentor’s experience was like in this program, click here and scroll to the second essay, “Initiation: The Making of a Deer Hunter.”

3. Indiana’s Learn to Hunt, Shoot, and Trap Program

Like many other state game agencies that have caught up with the times, Indiana’s DNR offers multiple workshops and mentoring options. The available sessions vary depending on what would-be hunters need out of them. Some sessions are short and very specific. These are 1- to 3-hour long seminars on topics like calling turkeys, selecting firearms, or cooking wild game. The next tier of involvement involves multi-day workshops that span the classroom, range, and field, and culminate in hunts. Small-group mentored hunts are also available.

Looking for a program in your own state? Some nationwide organizations like Backcountry Hunters and Anglers offer mentoring programs on a state-by-state basis (like their Idaho chapter). You can also find contact info for your state’s R3 representative here, as well as NGO contacts for organizations like Ducks Unlimited, Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, and more.