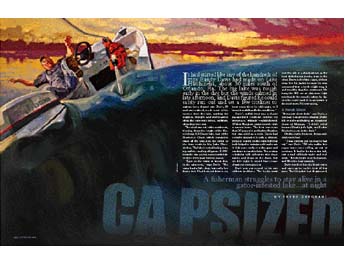

It had started like any of the hundreds of trips Randy Davis had made on Lake Hatchineha, about 30 miles south of Orlando, Fla. The big lake was rough early in the day, but the winds calmed in late afternoon, and Davis figured he could safely run out and set a few trotlines to capture some channel cats. Davis, 58 and semi-retired, made most of his income from the lake, guiding for crappies, bluegills and shellcrackers when the runs were prime, catfishing when they were not.

The wind was out of the northwest, blowing down the length of the five-mile-long, 6,500-acre lake, part of the Kissimmee Chain, which transports water all the way from the center of the state south to big Lake Okeechobee. The lake is noted for big bass, big catfish…and big alligators. A 600-pounder was among many giants taken there in the past hunting season.

“I got on the water at about four in the afternoon,” says Davis. “The water had a little chop, but really less than a foot. I had been out there in my boat many times in whitecaps, so I knew it could handle the conditions.”

Davis’s catfish boat was a classic garage-built Southern trotline rig known as a “skipjack”-a high-bowed, 17-foot fiberglass center-console with a narrow beam. The boat was more than 20 years old and had no flotation but was solid as a rock. Davis had recently upgraded it with a slippery polymer coating on the outer hull that both helped to waterproof it and made it slide more easily over the grass and sandbars around the lake. The coating is popular with airboaters who chase gators and frogs on the chain, but on this night it would have near- disastrous consequences.

Davis put out several of his sets without problems. The hooks went over the side in a steady stream as the boat drifted along slowly, stern to the wind. Davis, to his later regret, did not wear his life jacket because he was concerned that a hook might snag it and possibly drag him overboard. He hung the PFD on an aluminum light pole beside the console, where he figured he could reach it in an instant if the need arose. He was wrong.

A Freak Wave

“It was just about dark,” says Davis, a compact man given to wearing Dickie bib overalls and taking an occasional chaw of Morgan. “I didn’t mind because I had a pole light, and I often finished my sets in the dark.”

On this night, however, things suddenly went bad.

“I was running out my next to last set,” says Davis. “All of a sudden this rogue wave came rolling up out of nowhere. It had to be three feet tall, just a wall of black water and real steep.” It rolled right over the transom and filled the boat instantly.

Davis tumbled into the black water and came up to see his boat all but gone. The life jacket had disappeared, and the dark shore was at least a quarter mile away. He knew immediately that he was in big trouble.

The boat had sunk straight down at the stern, but fortunately the bow compartment had trapped a bubble of air. About 3 feet of the bow remained just above water.

Luckily for Davis, the water was relatively warm, probably in the high 60s. This factor would become critical as the night wore on. Hypothermia can set in quickly at low water temperatures, but survival time increases dramatically in higher temperatures-and Davis was going to be in the water a long time.

[pagebreak] He was wearing his favorite overalls, a T-shirt and a quilted jacket, plus tennis shoes. He decided to keep his clothing on and to stick with the boat, remembering tips he had picked up as he’d trained for his captain’s license, a requirement for running guide trips.

“The shore was far enough away that I wasn’t confident I could swim to it without a life jacket,” he says. Now the coating Davis had put on his boat’s bottom became a problem.

“I tried to climb up on the bow to get out of the water, but e coating was so slick I just kept slipping back off,” says Davis. “I tried for maybe two hours and it was just exhausting me. I noticed then that my bow line was trailing loose, so I gave up on getting out of the water and rigged a sort of harness that I could halfway sit in.”

In the meantime, Davis’s wife, Debbie, had left their home to go to church. Davis had expected to finish his set shortly after dark, return home and then join his wife at the church.

The Search Begins

By 9:30, Debbie, still at the church, was becoming concerned that Randy had not arrived. She called the house and there was no answer. When she got home and found that he hadn’t returned, she felt sure something had gone wrong. She called some of Randy’s friends, who quickly decided to call Florida Fish and Wildlife officers and the Sheriff’s departments in Polk and Osceola counties. Around 11 p.m., two helicopters were in the air over the lake. Davis watched them working back and forth, sometimes coming painfully close, but neither of them spotted him.

“One came close enough that I could have hit it with a stone, but it went right on by,” Davis says. Soon, Davis’s legs were numb from the rope saddle, so he began to alternate positions, sliding down into the water and putting it around his arms until that began to hurt too much, then going back to sitting. “I could see airliners going out of Orlando airport. I could see the light in the sky from Disney World. Life was going on and I was out there alone in the dark,” says Davis. “It wasn’t a good feeling. Then I got to thinking about my grandson, who is just eighteen months old, and how I wanted to teach him to fish, and I just refused to give up.”

[pagebreak] Davis also knew there were still plenty of big gators cruising the lake because of the warm fall. He kept telling himself that gators leave people alone if people leave them alone, and he tried not to think about them.

Toward morning, he was starting to get cold and weak, and it was getting harder and harder to raise himself back into the rope saddle.

“The helicopters stayed out there going back and forth all night, and then a while before daylight they disappeared. I don’t know if maybe they went back to get fuel at the same time or what, but my heart sank when they went away,” says Davis.

Davis hung on, so tired now he could barely keep his head above water. To make matters worse, the wind started to pick up. Waves slopped into his face, making it tougher to breathe and causing him to choke occasionally.

Overhead, officers from the Polk County Sheriff’s Department were taking advantage of the growing daylight. Pilot and deputy sheriff Craig Hardcastle, a retired Marine with experience flying military rescue missions, flew his Kiowa surplus chopper around the perimeter of the lake, checking to see if perhaps Davis had found his way to shore. When that produced no result, he began flying a grid back and forth across the lake. It was then that he spotted the capsized boat.

“He was so tired that he didn’t even wave when he saw me,” says Hardcastle. “He just looked up and then dropped his face back into the water.”

The pilot quickly called in boats from nearby Camp Mack. An airboat arrived first, but the design of the boat made pulling Davis out of the water tough. Minutes later, a larger boat with a swim platform on the stern arrived and eased in close.

“They told me to get out of the saddle and swim to them, but I was so weak from the cold I couldn’t have swum a stroke,” Davis says. The rescuers quickly backed down and two of them grabbed Davis by his jacket and snatched him out of the water. He bounced across the gunwales and cracked a rib, but he was very, very happy to be alive. He had been in the water more than 12 hours.

When emergency medical technicians took his temperature, it hovered at 95.3 degrees.

“They told me another degree or so and I would have been unconscious and that would have been it,” he says.

Davis’s tough old boat was towed in, turned over and pumped out. Davis is getting a new motor for it-along with several large blocks of foam flotation that will fit under the seats. He also vows never to leave the docks again without wearing a life preserver.

“The lake taught me a lesson that night,” he says. “And it gave me a second chance. I intend never to put myself in that position again.”red at 95.3 degrees.

“They told me another degree or so and I would have been unconscious and that would have been it,” he says.

Davis’s tough old boat was towed in, turned over and pumped out. Davis is getting a new motor for it-along with several large blocks of foam flotation that will fit under the seats. He also vows never to leave the docks again without wearing a life preserver.

“The lake taught me a lesson that night,” he says. “And it gave me a second chance. I intend never to put myself in that position again.”