THE WHOLE THING got started when Bob Jenkins’ second oldest daughter was accused of shoplifting a brassiere at Modene and Mabel’s Discount Variety Store.

Bob (whose full name is Robert E. Lee Jenkins), like most folks who live on the lower end of Washington County, took his daughter’s troubles to Fry (for Friedman L.) Bacon, a lawyer of some local repute. Fry Bacon is one of the last of that dwindling species of attorneys once admitted to the bar after a period of having “read law,” but with no other formal training. This shortcoming has been of no noticeable difficulty to Fry Bacon, who describes himself as a champion of poor people’s causes, and in return for legal services, has been known to take chickens, coon hounds and enough odd parcels of land to make him the county’s biggest property owner.

Not one to let textbook law interfere with a good courtroom battle, Fry Bacon’s favorite tactic is to open his Bible to some random page, wave it in the faces of judge and jury, shout that there is no higher law than the law of God, then have the jury get down on its collective knees while he leads the jurors in prayer for his dear misguided client, who has just recently been washed in the blood of the lamb and aims to spend the rest of his life doing kind deeds and “helping out widder women.”

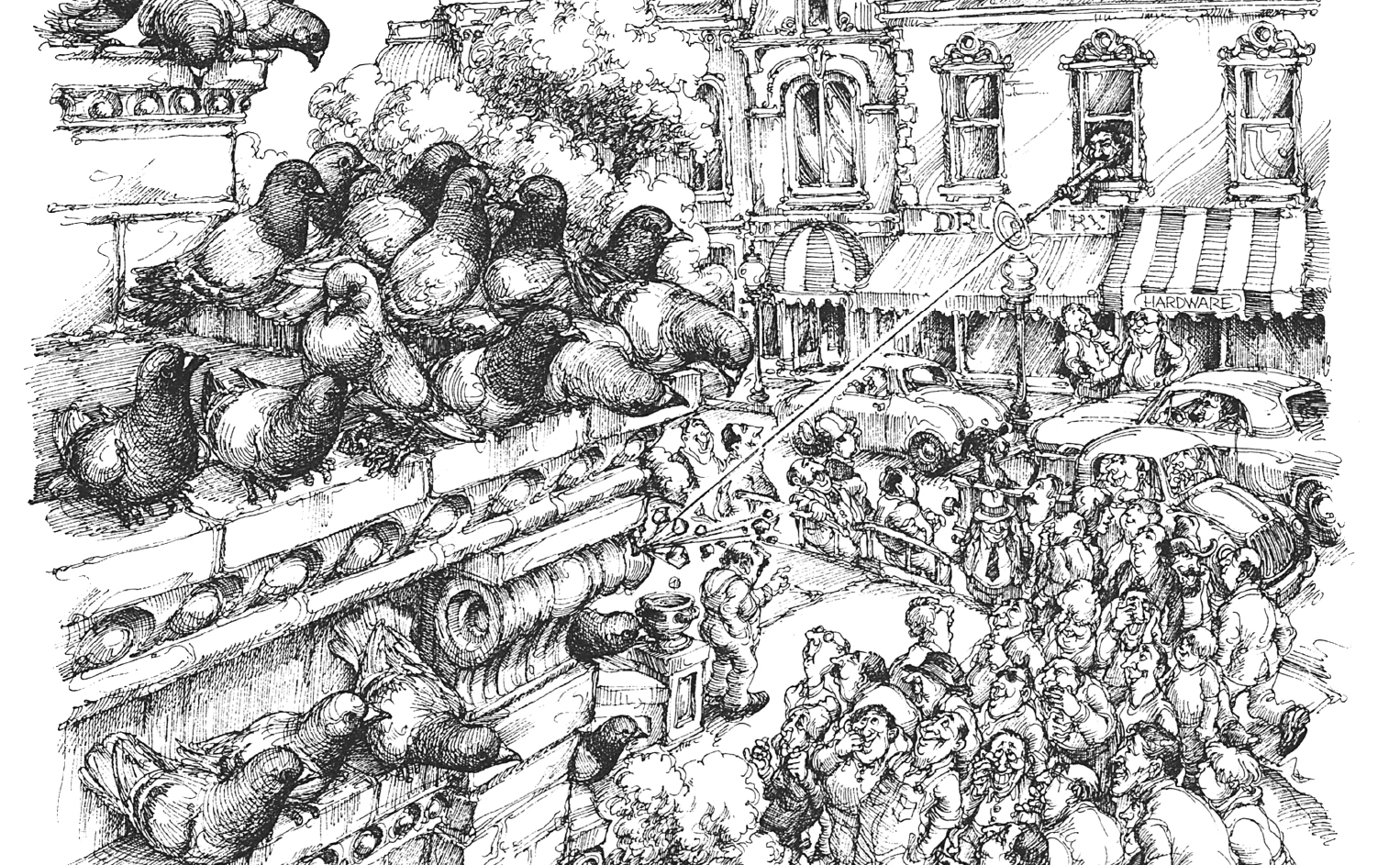

No one could dispute that the courthouse needed to be rid of the pigeons, and it was equally clear that the only way to do it was to shoot them.

Fry Bacon was just the man to represent Robert E. Lee Jenkins’ daughter. In Fry Bacon’s opinion the theft of a brassiere was a rather delicate subject and hardly one to be discussed before a courtroom audience. The word, brassiere, was abhorrent to him under such circumstances, as was the diminutive form “bra,” so he substituted “set of briars,” thumping his fists to his chest to indicate their approximate purpose and his own apparent meaning.

The case did not go well for Fry Bacon. His assertion that the poor girl was feeble-minded did not produce the desired effect, nor did his pleas that the lass was “with child” by a stranger last seen two years before. Seeing no hope in this line of defense, he turned to attack the two eyewitnesses as “godless sinners” and “short-skirted harlots” and was just warming to this line when it happened.

Six tons of pigeon manure came cascading through the courtroom ceiling. It covered the jury, it covered the godless harlots, it covered Hizzoner the judge and it covered Fry Bacon. It covered them with six tons of dry, dusty, choking pigeon droppings that had been accumulating in the courthouse attic for decades, straining at the ceiling rafters and needing only the shock wave of Fry Bacon’s rhetoric to set them free.

“Ladies and gentlemen of the jury,” Fry Bacon is reputed to have said when the dust cleared, “behold the wrath of the Lord.”

The case was dismissed and the courthouse closed for six weeks because, as one Jonesboro wag put it, “’The wheels of justice can’t turn in that stuff.”

The episode occurred not without some warning. About 15 years earlier, Bill Bowman, a leading Jonesboro humanitarian, had noted that the pigeons had so gummed up the courthouse clockworks that each hour was lasting about 80 minutes. The matter had been brought up at the City Council meeting, where Virgil Meeks suggested that the additional time was probably a good thing and the clock should not be tampered with. The Council agreed and voted 11-1 to leave the clock alone.

But the collapse of the courtroom ceiling meant something had to be done. The first order of business was to clear out the mess, and that in itself brought about a political scandal which almost brought down the county government. The lowest bid to haul away the pigeon manure ran into some thousands of dollars, enough to cause a countywide financial crisis, but at the last minute Mort Screeb, who owned a tomato farm down by the Chucky River, stepped in and said that the stuff was great tomato fertilizer and that he would haul it off for nothing. His one condition, however, was that he be allowed to take it as he needed it, which, questioning disclosed, might cover three or four years. In the end a cleanup crew was hired to cart it off, but the ensuing political fight, with Screeb screaming kickback, produced a shakeup in Washington County politics which continues even to this day.

Despite all the uproar a few cool heads noted that nothing was being done about the pigeons. They were as happy as ever, perching on the belfry railings, roosting in the clockworks, building more nests, hatching chicks and contributing hourly to another avalanche.

The county’s first step was to hire professional exterminators. They rigged a cannonlike affair which made a burping noise guaranteed to frighten pigeons and starlings and other winged creatures. The Jonesboro pigeons loved it. It would burp and they would coo, and in winter they warmed their feet on its outstretched muzzle. Obviously, stronger measures were called for. That’s when I arrived on the scene.

Jonesboro is not quite like anyplace else on earth. It’s a beautiful little town nestled in the wooded valleys of East Tennessee. It was once the capital of the lost state of Franklin, was home to a scrappy young lawyer by the name of Andy Jackson and now, after 200 years, is one of the best preserved towns of its kind anywhere. No power or telephone lines ensnare its streets, no parking meters clutter its curbs and old-fashioned street lamps cast a warm glow on brick-paved sidewalks.

On the town square is the county courthouse, where dwell Jonesboro’s pigeons. Though completed in 1912 it is still called the “new” courthouse by most of Jonesboro’s citizens who well remember the “old” courthouse, and probably the one before that.

The distance to the peak of the clock tower was 41 yards, and the choice of weapons was my old pump-up pellet rifle. I figured this was the only safe equipment for the job even though it might handicap me a bit.

Stray dogs, camels and pack mules eventually find their way home, and it is no different with wandering Jonesboroites. After several years of living in the West and exploring lands far beyond, I returned to Jonesboro to spend my declining years near the poor dirt farm where I grew up.

Citizens of Jonesboro seldom leave town except in a state of acute disgrace, so it was naturally assumed when I left that there must have been substantial reason. This meant I was eyed with some suspicion when I reappeared on the village green. But I opened up a downtown office just as bold as brass, looked up old girlfriends and settled back in place as easily as a pup taking a nap. Whatever crimes or indiscretions that vivid imaginations may have conjured to account for my departure were apparently forgotten.

It was a comfortable reunion but alas, too good to last. When I moved into my second-story office directly across from the courthouse and laid eyes on all those grinning pigeons lined up on the balcony I knew fate had caught up with me.

No one could dispute that the courthouse needed to be rid of the pigeons, and it was equally clear that the only way to do it was to shoot them. Their clocktower fortress was apparently impregnable to all other forms of attack. But until my arrival no one had possessed both the will and the means of dealing with them. My office window provided the perfect sniper’s roost. Destiny surely planned the whole thing.

As discreetly as enthusiasm permitted, I passed the word that I wouldn’t mind taking a few potshots at the pests “just to keep my eye in practice.” And just as discreetly the word came back that it was my “bound civic duty to rid the town of the damnable beasts.” Even the sheriff, H.H. Hackmore, who is in charge of courthouse maintenance, stopped by to bestow his blessing.

Second only to the speed of light is the blazing speed of Jonesboro gossip. In no time at all everyone knew that a big game hunter had come to do in the courthouse pigeons.

The distance to the peak of the clock tower was 41 yards, and the choice of weapons was my old pump-up pellet rifle. I figured this was the only safe equipment for the job even though it might handicap me a bit. I didn’t know just how much of a handicap this rifle would be until I tried adjusting the aperture sight for a 41-yard dead-on point of impact. The pellets hit everywhere except dead-on, with the group sizes ranging upwards of 12 inches.

I’d made the mistake of announcing that I would begin knocking off the pigeons on the following Monday morning. I say mistake because when I arrived at my office opposite the courthouse, pellet rifle in hand, a crowd of onlookers had already gathered in the street. It was going to be a memorable day in Jonesboro, they reckoned, and they wanted to see it happen. There was a smattering of applause as I entered the ancient building, and I heard Harry Weems, who runs Harry’s Men’s Shop downstairs, offering to cover all bets. I wish I could forget the whole thing.

Read Next: The Best Pellet Rifles, Tested and Reviewed

Filling the rifle’s air reservoir with 10 full strokes of the pump handle, I fed a pellet into the chamber, and taking a rest on the window sill, leveled the sights on a particularly plump pigeon. The crowd below held its breath. Plufft went the air rifle, splat went the wayward pellet on an ornate piece of concrete scroll work, coo went the pigeon. I’d missed clean. A chuckle rippled through the throng.

Feverishly I pumped the rifle and fed another pellet. Plufft, splat, coo. The chuckle became a collective guffaw. Plufft, splat, coo; again and again I tried. No results.

“Hey Carmichel,” someone shouted from below, “if them was lions they’d be pickin’ their teeth about now.’”

Plufft, splat, coo. Even the pigeons joined in the fun, waddling over to the roof’s edge for a better view of the whole sorry spectacle.

By then my audience was drifting off by twos and threes, telling each other it was the biggest disappointment since Jack Hicks’ hanging was called off in the spring of 1904. Harry Weems paid off his losses and my disgrace was thus complete.

That day I called Robert Beeman, the country’s leading dealer and importer of quality air rifles and accessories, and ordered a German-made Feinwerkbau Model 124 air rifle and a supply of special pointed pellets. The FWB-124 is the hottest thing going in hunting-type air rifles. It gives a muzzle velocity of better than 800 feet per second (close on to a .22 Rimfire Short) and is accurate enough to hit a dime-or a pigeon’s head-at 41 yards. “Send it airmail,” I told him. “I’ve got to salvage my reputation.”

Revenge would be mine, I told everyone, describing the fancy new air rifle I’d ordered. But sometimes the airmails fly slowly, and it was weeks before the FWB-124 arrived. By then the whole town was laughing about the “wonderful pigeon gun” that existed only in my imagination.

But it did arrive, and my first few test shots showed it was more accurate than I had dared hope. Topped off with a 10X scope and zeroed dead-on at 41 yards, it cut a neat little group about the size of a shirt button.

The next morning a small crowd of onlookers gathered to watch the next chapter in Carrnichel’s disgrace. Even the pigeons seemed interested, and about 20 lined up on the balcony railing to see what was happening. I started on the right end of the row and worked my way to the left.

The first bird toppled off with scarcely a flutter. Its neighbor noted its demise with idle curiosity but no particular concern. When the next two or three went over the edge the others began to get somewhat curious about what was happening and cooed at the stricken forms with some amazement. In fact, as more pigeons fell, the remainder reacted with increasing amazement, those on the left end having to lean far out from their perches, wings aflutter, in order to watch the peculiar behavior of their brethren.

The first run was 14 straight kills with Harry collecting bets like mad. The pigeons still hadn’t figured out what was going on, but apparently they thought it best to go somewhere else and give it some thought. That day’s tally was 27 pigeons and a few stray starlings. Next day would be even better. But next day disaster arrived in a totally unexpected form. I was brewing a pot of tea and had just killed the first pigeon of the day when “Shorty” Howze, Jonesboro’ s 7-foot policeman, charged into my office and presented me with an official complaint lodged by one of the townspeople. According to the unnamed plaintiff, I was “molesting Jonesboro’s beloved pigeons.”

“C’mon, Shorty,” I protested, “you’ve got to be kidding. Everybody wants rid of those pigeons. You told me so yourself. And besides, I have the sheriff’s OK.”

“I know,” Shorty replied. “The courthouse is county property and you can shoot over there all you want to. But the chief says when you shoot across the street you’ re violating Jonesboro air space. So the complaint stands.”

“Who complained?” I asked.

“I’m not allowed to say.”

“I know, but tell me anyway.”

“That crazy-acting woman that just moved into the old Crookshanks place.”

“The one that has all the cats and makes her husband walk the dog at two in the morning?”

“That’s the one.”

“Thanks for telling me.”

“By the way,” he said, stopping at the door and glancing at the air rifle by the window, “that’s one hell of a pigeon gun.”

Except for an occasional guarded shot, the rifle stood unused. The pigeons flourished and grew fatter, and life in Jonesboro trudged through an uneventful winter. By spring I’d all but forgotten the ill-fated affair when a really splashing event brought the pigeon problem back into brilliant focus. The leading character was none other than one Judge Hiram Walpole Justice. It seemed that Judge Justice, all decked out in his new tailor-made blue suit, had just handed down an important decision and was on the courthouse lawn discussing it with some reporters when a pigeon swooped down and scored a bull’s-eye on his jacket. Thousands saw it live on TV.

The judge turned on his heel and stalked back into the courthouse, muttering something about the futility of “holding court in a chicken house.” That afternoon Judge Justice was in my office learning the finer points of shooting courthouse pigeons with a FWB-124.

Every morning thereafter, the Judge would declare a recess at about 10 o’clock and rush over to my office to blast a few pigeons, giggling fiendishly every time one plopped on the pavement. Hizzoner became a very fine marksman.

This had been going on for about two weeks when one morning Shorty, backed up by the mayor and two constables, crashed into my office and waved a warrant at the backside of the judge. “Aha,” yelled the mayor. “We know what you’ve been up to, Carmichel. This time we’ve got you dead to rights.”

With his judicially robed backside to the door, the judge was kneeling on the floor and taking a careful aim with the rifle resting on the windowsill. So intent was he that he didn’t even look up.

Every morning thereafter, the Judge would declare a recess at about 10 o’clock and rush over to my office to blast a few pigeons, giggling fiendishly every time one plopped on the pavement.

“That ain’t me,” I said, stepping out of the washroom. “That’s Judge Justice. And if I was you I wouldn’t bother him right now.”

All worthy projects must end, and by late summer the Judge and I had pretty well wiped out the pigeon population, firing something near 1,500 pellets in the process. In all probability the whole thing would have reached a happy conclusion had it not been for one of those freak, clod-dissolving August cloudbursts. The creek overflowed its banks, poured into the streets of Jonesboro, and for the first time in history, flooded the courthouse basement where two hundred years of moldy Jonesboro records are kept. The devastation to the voting records in particular was total. Wiped out.

Read Next: The Best Shotguns for Bird Hunting, Tested and Reviewed

An official inquiry was launched in order to discover the cause of the unprecedented flooding, and the final ruling was:

“One Jim Carmichel, a citizen of Jonesboro, is known to have shot pigeons on the courthouse roof and thereby stopped up the gutters and drainpipes, thus contributing to the flooding.’”

There’s a new crop of pigeons living in the clock tower now. I can see them looking this way….

(All statements of fact in the story you have just read have been checked and found accurate. Certain names and dates have, however, been altered to protect wrongdoers. —Ed.)

This story first ran in the March 1980 issue of Outdoor Life, and included the editor’s note above.