Wherever I go, someone always asks me to name my favorite type of hunting. It’s a fair question, and it deserves an honest answer. But usually I’m forthcoming with only a politely noncommittal “Whatever I happen to be hunting at the time” and let it go at that. The reason I’m evasive is because even a hint of my true hunting passion invariably provokes shocked outrage or a cascade of questions. You see, my true hunting love is elephants. African elephants.

People who don’t know anything about elephants can’t understand why I’d want to hunt them. The only elephants they’ve ever seen are the cuddly pachyderms that munch peanuts and trot around circus rings with pretty girls astride their necks. Those are Asian, or Indian, elephants. They can be recognized by their small size, stubby ivory and stunted ears dangling from their heads like limp rags. African elephants are another beast entirely. Half again or even twice as big as the Indian variety, they weigh up to five tons or more, and may stand over 10 feet at the shoulder. They have giant ears that extend like barn doors when they want to exhibit a temper or merely announce their magnificent presence. No wild creature on earth is as fascinating or as intelligent–or as dangerous.

For many, elephant hunting becomes a consuming passion. Legendary ivory hunters such as Selous and Bell lived that passion. Like a compulsive gambler who is good-or lucky-enough to make a living in the casino, these hunters didn’t care about winning; their passion was doing it. If this were the age when herds of elephants freely roamed the African continent, I would chuck it all and go there forever. Hunting elephants is in my blood and they are in my dreams.

Hell Hath No Fury

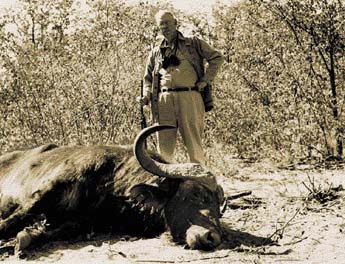

Unlike the ivory hunters of legend, I cannot count my elephants by the hundreds or weigh my ivory by the hundredweight, but for adventure I’ll match anyone’s encounters-beginning with the cow that tried to grind my bones into the red dust of Africa on my very first safari. We’d picked up the tracks of a good-sized herd that appeared to be meandering through the broken forest bordering the vast Okavango Swamp. My guide, the late Pat Hepburn, a pair of his trackers and I had made our way close enough to hear the elephants ripping the branches off trees when suddenly all hell broke loose. There was a great thundering of earth, a crashing of brush and the shrill trumpeting of an elephant stampede, but we knew we weren’t close enough to have spooked them. Running hard to keep up, we heard more trumpeting and back-and-forth crashing as if the herd was stampeding in circles; then it was suddenly quiet and we slowed our pace, trying to sneak in close enough for a look.

I scrambled up a towering termite mound hoping to see over the brush. Just as I got on top, a smallish elephant broke through the trees and came charging directly at us! My first reaction was that it was only a young bull like those I’d seen on previous days, showing off with adolescent threats before turning and scurrying away. If I’d had more experience then, I would have known that this beast meant deadly business, because instead of flaring its ears-in the typical threatening pose-this one’s ears were laid back flat. Any lingering misconceptions I may have held vanished when the onrushing animal crashed through a rotted tree trunk exploding it into flying fragments. The damn thing meant to destroy us just as it had the tree!

Though I had a better view of the charging elephant than Hepburn did, he was quicker to figure out what was happening. When I jumped from the termite mound he was yelling and waving his arms at the animal, trying to make it understand what we were. In a final desperate attempt he fired a shot over its head, but to no use. The second bullet from Pat’s rifle hit high on the elephant’s forehead, smacking a puff of dust and rocking its head back like a batterinram.

It hesitated, and for an instant I thought it would turn, but then it regained momentum and there was no doubt it would kill us or die. The world switched to slow motion then, and when I raised my rifle the crosshairs seemed to casually wander across the elephant’s wide forehead, probing for a route to its brain. It seems so uncomplicated, I later remembered thinking, the power of a trigger finger challenging the might of an elephant, as if I were only a bystander watching the duel from a safe sideline. Then the vast form became motionless, and then it was very silent. I heard no bird sounds or whispers in the trees, as if all of nature was made breathless at what it had witnessed. Neither Pat nor I spoke for a long while. What does one say an arm’s length from crushing death?

But why did it happen?

That was answered minutes later when our trackers discovered the stillborn calf the cow had been guarding. The crashing stampede we’d heard earlier was the cow chasing other elephants away from the dead calf she’d been guarding. We’d come between her and the calf and her rage was the most powerful protective instinct in all of nature.

That episode was a turning point in my hunting career, or perhaps it was the real beginning. Like hundreds of African hunters before me, I became entranced by elephants and wanted to learn everything about them, including their 20th-century hunters, such as the legendary John Hunter; Bror Blixen, the husband of Out of Africa author Karen Blixen (also known as Isak Dineson); and Denys Fitch-Hatton, Karen’s doomed lover.

I even found an elephant’s skull and sawed it in half, so I’d know for sure the brain’s location, and, later, would follow herds of elephants using the crosshairs of my riflescope like a surveyor’s transit to determine the straightest route to their brain from any position. I read books and found diagrams about where to hit an elephant, but most were not very helpful because they showed only a frontal shot. The fact of the matter is that relatively few latter-day elephants are killed by frontal shots. Aside from my first experience, the others I’ve taken were with side shots to the brain, aiming at a crease just below the ear opening. Despite romantic lore, frontal shots usually aren’t a practical proposition in normal hunting circumstances because the last place you want to be is in front of a wild elephant. Except when they shade up during the day, elephants are usually moving. The trick is to sneak up behind them and find a shootable position from the side. Every elephant I’ve taken with a shot to the side of the brain fell toward the bullet. Other hunters tell me they’ve had the same experience.

Truth be known, most elephants bagged by sport hunters are killed by heart/lung shots. Professional hunters (PHs) often prefer that their clients use the heart shot for a number of reasons, beginning with the obvious fact that the heart is a much bigger target than the brain. Also, in situations where the herd is milling around, a heart shot may be the wise choice because the stricken elephant almost invariably takes off at a dead run, followed by its companions. When a brain-shot elephant thunders to the ground, its buddies sometimes run in screaming, panicky circles, and you’re just as dead when trampled by accident as when it is done on purpose. (More about this later.)

[pagebreak] Elephant Guns

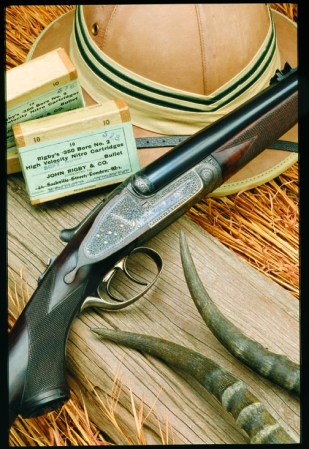

Elephant rifles and cartridges are the stuff of large books and lush legend. In few endeavors have gunmakers labored more magnificently than in the building of huge-bore double rifles for the elephant trade. Heft one to your shoulder and your imagination takes the fast lane. You see yourself firing a right and then a left, levering open the barrels, hearing the pinging ejection of jigger-sized brass cases and inhaling the exotic incense of cordite corkscrewing up from the twin chambers.

Back in the 1950s a Holland & Holland “Modele DeLuxe,” then the company’s best-grade double rifle, sold for about $1,350. A best-quality Rigby went for a bit less. That was pretty pricey in those days, but still a sound investment for someone wanting to get in the elephant-hunting business. Today, though, a best British double will set you back upward of $75,000, which means they’ve become the playthings of tycoons and nabobs, and explains why many of the old African professional hunters have long since cashed in their doubles and opted for relatively inexpensive bolt rifles. Four out of every five PHs I’ve hunted with carry only bolt rifles, and the few I’ve hunted with who own doubles uncase them just for special occasions.

The only time I’ve hunted with a double rifle was with a Grant & Lang that belonged to my PH. I accidentally lost one of the hard-to-find .500/465 Nitro Express cartridges and we spent half a day backtracking. After that I decided it wasn’t worth the bother and went back to using my bolt rifle.

The magical term “Nitro Express” applies to cartridges developed for smokeless or “nitro” powder. (Cordite is cotton treated with nitroglycerin.) Earlier cartridges made for the elephant trade were loaded with blackpowder; many of them are now known as BP Express calibers. Since blackpowder produced only moderate velocities (usually in the 1,500 to 1,800 fps range), energy was developed by using heavy, large-diameter bullets-a practice that continued after the advent of nitro powders that generated velocities over 2,000 fps and striking energies measured in the tons.

Until recently the most powerful cartridge for double-barreled elephant rifles was the fabled .600 Nitro Express, which delivered a thumb-sized, 900-grain slug at nearly four tons of muzzle energy. Then Holland & Holland brought forth a .700 Nitro of even greater power. I fired one of these at H&H’s London test site, and the best way I can explain the experience is that one shot definitely gets you out of the mood for a fast follow-up shot-especially at over $100 per pop. Yet I’m told that several rifles in this caliber have been ordered and there’s even rumor of an .800 Nitro. I’ll give that one a pass.

Before the invention of breech-loading rifles, the elephant gun was a massive muzzleloading affair, hurling hunks of lead nearly the size of golf balls. Back in the 1970s, I went on an all-blackpowder safari with Turner Kirkland, founder of Dixie Gun Works, which then, as now, was the world’s center for blackpowder firearms and accessories. Turner had a huge-gauge, double-barreled muzzleloader that had been made in Capetown, South Africa, for an early 19th-century elephant hunter. The round, cast-lead balls weighed upward of a quarter-pound apiece. When Kirkland test-fired it at our safari camp, the bullet felled a good-sized tree-a sight that caused Back in the 1950s a Holland & Holland “Modele DeLuxe,” then the company’s best-grade double rifle, sold for about $1,350. A best-quality Rigby went for a bit less. That was pretty pricey in those days, but still a sound investment for someone wanting to get in the elephant-hunting business. Today, though, a best British double will set you back upward of $75,000, which means they’ve become the playthings of tycoons and nabobs, and explains why many of the old African professional hunters have long since cashed in their doubles and opted for relatively inexpensive bolt rifles. Four out of every five PHs I’ve hunted with carry only bolt rifles, and the few I’ve hunted with who own doubles uncase them just for special occasions.

The only time I’ve hunted with a double rifle was with a Grant & Lang that belonged to my PH. I accidentally lost one of the hard-to-find .500/465 Nitro Express cartridges and we spent half a day backtracking. After that I decided it wasn’t worth the bother and went back to using my bolt rifle.

The magical term “Nitro Express” applies to cartridges developed for smokeless or “nitro” powder. (Cordite is cotton treated with nitroglycerin.) Earlier cartridges made for the elephant trade were loaded with blackpowder; many of them are now known as BP Express calibers. Since blackpowder produced only moderate velocities (usually in the 1,500 to 1,800 fps range), energy was developed by using heavy, large-diameter bullets-a practice that continued after the advent of nitro powders that generated velocities over 2,000 fps and striking energies measured in the tons.

Until recently the most powerful cartridge for double-barreled elephant rifles was the fabled .600 Nitro Express, which delivered a thumb-sized, 900-grain slug at nearly four tons of muzzle energy. Then Holland & Holland brought forth a .700 Nitro of even greater power. I fired one of these at H&H’s London test site, and the best way I can explain the experience is that one shot definitely gets you out of the mood for a fast follow-up shot-especially at over $100 per pop. Yet I’m told that several rifles in this caliber have been ordered and there’s even rumor of an .800 Nitro. I’ll give that one a pass.

Before the invention of breech-loading rifles, the elephant gun was a massive muzzleloading affair, hurling hunks of lead nearly the size of golf balls. Back in the 1970s, I went on an all-blackpowder safari with Turner Kirkland, founder of Dixie Gun Works, which then, as now, was the world’s center for blackpowder firearms and accessories. Turner had a huge-gauge, double-barreled muzzleloader that had been made in Capetown, South Africa, for an early 19th-century elephant hunter. The round, cast-lead balls weighed upward of a quarter-pound apiece. When Kirkland test-fired it at our safari camp, the bullet felled a good-sized tree-a sight that caused