SMOKE JUMPER A guy gets a queasy feeling in the pit of his stomach when he jumps out of an airplane and suddenly finds himself above the plane. But that happened once to Wayne E. Williams, 52, a U.S. Forest Service smoke jumper for the last 31 years. It was 1989, and Williams and a smoke-jumper crew were dispatched to a fire in the Gila National Forest in New Mexico. Once Williams and another jumper were out of the plane, a thermal grabbed them and lofted them above the aircraft. "We realized that, until this thermal let us go, we really wouldn't have much control over our parachutes," says Williams. "Then our greatest fear happened: The thermal carried us past our jump spot, and it let go of us when we were close to the fire itself." The men hit the ground a mere 10 feet from the fire and scrambled to a nearby rocky outcropping. They made it to safety just as the roaring flames rolled over the rocks, which shielded them from the blaze. Outdoor Life Online Editor

RESCUE SWIMMER Three young people had decided to go swimming at a spot where Lake Ontario meets high rock cliffs. But a big blow came off the lake, knocking them around. One struggled ashore and called the police to help the young man and woman still trapped in the water. Petty Officer Steven Ruh, 22, of North Boston, N.Y., and the crew of his 47-foot U.S. Coast Guard rescue boat, based at Coast Guard Station Oswego, N.Y., responded. When Ruh and his mates got there, the local fire department was rappelling down the cliff wall, trying to rescue the young woman. "But the waves were breaking into the wall," Ruh remembers. "Seven-, eight-foot waves at that point. So they couldn't get to the woman, because the waves were kicking the fire department guys up against the wall. She was just swinging back and forth, crashing into this jagged rock wall." Ruh quickly donned his surface-swimmer harness, fins and diving mask, and leapt into the water-the waves now 8 to 10 feet and rising-and swam more than 100 yards to the woman. "I had to time the waves properly, because they would have plunged me into the wall," Ruh says. "That was my biggest concern." He managed to get a life jacket around the woman, and his crew hauled them back to the boat. Her leg was punctured and broken, and she was fading in and out. But she survived and made a full recovery. Ruh was awarded the Coast Guard Medal, given to those who display extreme heroic actions at the risk of their own lives. Yet he doesn't consider the mission to be a complete success. The other person, the injured girl's boyfriend, drowned. Outdoor Life Online Editor

SEARCH-AND-RESCUE PILOT Lt. J.G. John Kirk, 30, from Lawrenceville, Ill., flies search-and-rescue missions as a U.S. Coast Guard helicopter pilot, patrolling the Great Lakes from his Traverse City, Mich., base. In December 2006, Kirk was flying a medevac mission when a blizzard slammed into Lake Michigan, forcing him to put down at Muskegon. Around midnight, though, a mayday was received, and he and his crew had to check it out. Visibility was a quarter-mile and fading. Terrain was a problem, too. "There's a little ridgeline right before you go out to the lake," says Kirk. "We had to cross it, which was pretty jerky because we had to pick our way out using ground references-like telephone poles-to avoid the towers. "When we got out there, the winds were just howling," Kirk remembers. "We were getting buffeted all over the place. Visibility at times would go down to absolutely nothing. You're just on the instruments on the aircraft, keeping her level while trying to search the water [using night-vision equipment]." Kirk and his crew searched for more than two hours, saw nothing and headed back. "We got back to that ridgeline, and we actually had to drive up and down, north and south along the shoreline, looking for a spot where we could get over the ridge," he says. Ice was building on the rotors, and they were seriously considering beaching the copter when they finally saw a low spot in the terrain where they could cross. Kirk never heard anything about the mayday caller, but for his crew it was just another day on the job. Outdoor Life Online Editor

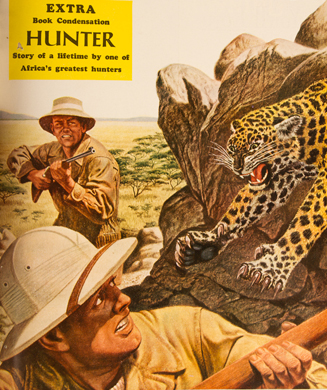

PROFESSIONAL HUNTER Professional African Hunter (PH) Jeff Rann (left in photo) was on the track of a leopard that had been wounded by a client. The leopard had been shot in the shoulder. "That should have been a killing shot," Rann, 52, says. Rann and the hunter followed the blood trail, eventually bumping into and scaring off several lions. At Rann's feet lay a pool of dark leopard blood. Rann assumed the lions had killed the leopard and was angry he'd lost a trophy animal. He admits he was distracted. And it was then that the very alive leopard pounced. Rann fired, but missed. Outdoor Life Online Editor

COMMERCIAL FISHERMAN You want high-paying danger? Work a Bering Sea crab boat. "There's like a ninety-nine percent injury rate," says Captain Johnathan Hillstrand, 45. "We've got a guy onboard who already broke an ankle. I hurt my arm really bad. There's so many ways to get hurt out here. A lot of ways to die, too." Based out of Dutch Harbor, Alaska, on the Aleutian Islands, Hillstrand captains the Time Bandit, a 115-foot crab boat that has a crew of six and was featured on the TV show Deadliest Catch. They work in any condition-roaring seas, wicked winds, snow squalls-to haul up and empty crab pots, steel cages about the size of a collapsible camper that, when full of squirming king crabs, can top 1,000 pounds. It's treacherous work. But on a good boat, a crew member can make $20,000-a month. Broken bones? Real common. "We've lost fingers, too," Hillstrand says. "But nothing big. No broken backs, anything like that." Outdoor Life Online Editor

CONSERVATION OFFICER In the early-morning gloom, the three game wardens and three deputy sheriffs crept up the steep, brushy slopes near Los Gatos, Calif., searching for a suspected marijuana field. They found it-more than 20,000 plants, valued at several million dollars-and they were about to seize it. But two men guarding the pot field had other ideas. "One had a sawed-off shotgun, the other an AK-47," says California Department of Fish and Game Officer Kyle Kroll, 27. "I actually faced the guy holding the shotgun, had my rifle pointed at him. That's when the other guy started shooting," he says. A bullet took Kroll high in his left leg and came out near his hamstring. It then pierced his right leg and exploded, exiting from a couple of different places in the back of the leg. During the brief firefight, the man with the shotgun was killed. Kroll's shooter got away. Meanwhile, the officer applied direct pressure to stop the bleeding. As he waited three hours for a helicopter to airlift him to a hospital, it took all Kroll had to fight off shock. That occurred in August 2005. By early 2006, Kroll was back on the job, albeit with lingering pain. His legs are also weaker now, given the muscle mass he lost when his legs were repaired. Drugs have hit rural California with a vengeance, and Kroll, a lifelong hunter and angler, feels that drug eradication is a good thing for conservation. Pot growers douse their illegal plots with fertilizer and pesticides, toss around trash and frequently poach fish and game. Fewer druggies, he says, means more wildlife. But between the all-too-prevalent pot growers and meth-lab operators, the job's getting more and more dangerous. And as the line between poacher and druggie continues to blur, those people who used to accept an arrest now try to run over officers with their quads, or, as in the case of Kroll, start shooting. And it's not a situation that is likely to change anytime soon. Outdoor Life Online Editor

BUSH PILOT Joe Darminio's voice goes up an octave when he describes the crash that probably used up whatever extra lives this bush pilot had to his credit. "The one I shouldn't even be sitting here on, that happened on my birthday, August 21, 2001," says Darminio, 41, of Anchorage, Alaska. "I knew I was going to die." Darminio had accepted a last-minute trip from another air service, flying four anglers to the Newhalen River, southwest of Anchorage. But the plane had a defective control cable, which snapped at 200 feet above the Newhalen, as the plane was flying at 110 miles per hour. "We basically became a big lawn dart," says Darminio. "The airplane flipped upside down and went out of control, landing face-first in the river. Outdoor Life Online Editor

The most dangerous jobs in the outdoors.