We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

Before laser rangefinders and FFP MRAD-turreted riflescopes maximum-point-blank-range, or MPBR, was the best way that you could set up for success while shooting at longer distances. It’s still got a strong following today. Essentially, MPBR is a calculation of the maximum distance at which you can hold dead center and still hit a target of a given size. It takes into account your rifle’s velocity, trajectory, and both distances at which your bullet will impact exactly where you aim during its parabolic flight. Within this MPBR distance, it gives the hunter a simple point-and-shoot solution and is the darling of flat-shooting aficionados. There’s just one problem. The dispersion of your rifle radically degrades the benefit to using MBPR for distances beyond 300 yards.

Max-Point-Blank-Range In Theory

Leveraging MBPR, in its time, was a best practice. Working with the tools available, it did allow hunters to more effectively place shots at longer distances than they otherwise may have. However, hunters were likely subjected to even more sabotage of their max-point-blank dreams by their equipment and shooting styles, and lots of animals were missed and wounded in those days. Still, it was a good idea.

A bullet’s path is parabolic. Knowing the muzzle velocity, sight height, and drag coefficient of the bullet, one can calculate the trajectory. Hunters figured out that if they chose an appropriately-sized target to mimic the vital zone — an 8-inch circle for instance, for a deer — they could also calculate the maximum distance at which they could hit the target without changing their aiming point or favoring high. MPBR gives a distance which brackets this flight path. The bullet will arch from low to high, then back below line of sight. This is appealing to anyone who isn’t using a scope with holdover subtensions or adjustable turrets — especially at unknown distances.

Take for example the new, flat-shooting 25 Weatherby RPM with its ultra-slippery 133-grain Berger factory load leaving the muzzle at 3,000 fps. If you sight in at 3.2 inches high at 100 yards, your bullet will strike 4 inches high at about 160 yards, your zero will be at 287 yards, and the bullet will strike the bottom edge of the target at 339 yards — the system’s max-point-blank range. You can figure this out using a simple MPBR calculator. Armed with this information, you can hold dead on your target to that distance and still score a lethal impact.

Dispersion: The Missing Factor

In theory, MPBR can allow for some shockingly effective distances with flat-shooting cartridges using high-B.C. bullets, but if you use it enough, you’ll find yourself making marginal hits or missing an unsettling number of shots. One reason is dispersion — the random distribution of shots within your rifle system’s capability. Most of us think of this in terms of group size, but a cone of fire is another helpful way to consider it. No rifle puts every shot through the same hole, and that dispersion pattern, which may measure one inch across at 100 yards, grows at longer distances. A calculation of MPBR does not take this into account.

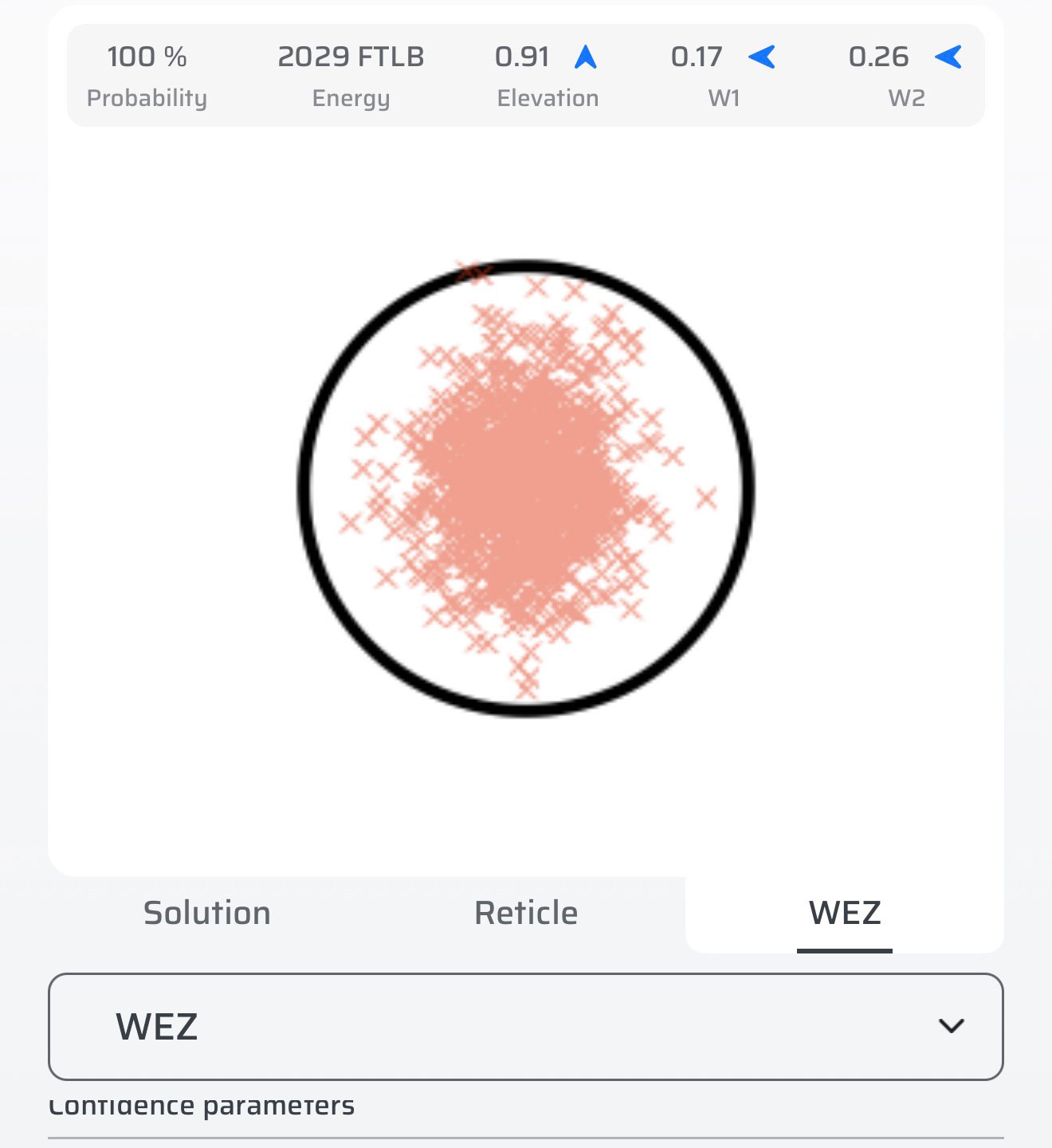

What does our previously-mentioned new 25 WBY RPM cartridge look like when we have a rifle with a true cone of dispersion of 1.25 MOA? When using sample sizes of 20 shots, this is pretty representative of the upper portion of factory hunting rifles we have tested. Using a valid sample size of 20, or even 30 shots will give you a much more accurate representation of your rifle’s level of precision.

With a dispersion pattern of 1.25 MOA, we can expect any shot we take from the rifle to land within a 4.4-inch circle at the MPBR of 339 yards. The top half of your dispersion pattern will hit in the bottom 2.2 inches of the target, and half your shots will miss low. Taking dispersion into consideration, the longest shot where your cone of fire will reliably land on target is about 312 yards. Beyond that, you’re testing lady luck.

The Human Factor

The dispersion of 1.25-MOA listed above considers an ideal shooting scenario, including a prone or bench rest with rear support under good conditions. Any reasonable hunter would admit that there’s a difference between test precision and field precision. Most hunters would do well to achieve 2-MOA precision with their rifle system on game — and that’s generous. So, what does our MBPR scenario look like if we consider a 2-MOA shooter and rifle and want to reasonably expect all our shots to hit the 8-inch vital target?

At our calculated max-point-blank-range of 339 yards, our dispersion will be approximately 7.1 inches — nearly the size of the target. At that distance, with a perfectly-centered zero, half the shots will impact the lower half of the target, and the other half will miss low. The farthest distance you would reliably hit the target using MPBR would be around 300 yards. Beyond that, you’ll start to shoot low.

This is also assuming we have a nearly perfectly-adjusted zero on our rifle. Any error here will compound and frustrate you with head-scratching misses as well.

Do Flat-Shooting Cartridges Actually Matter?

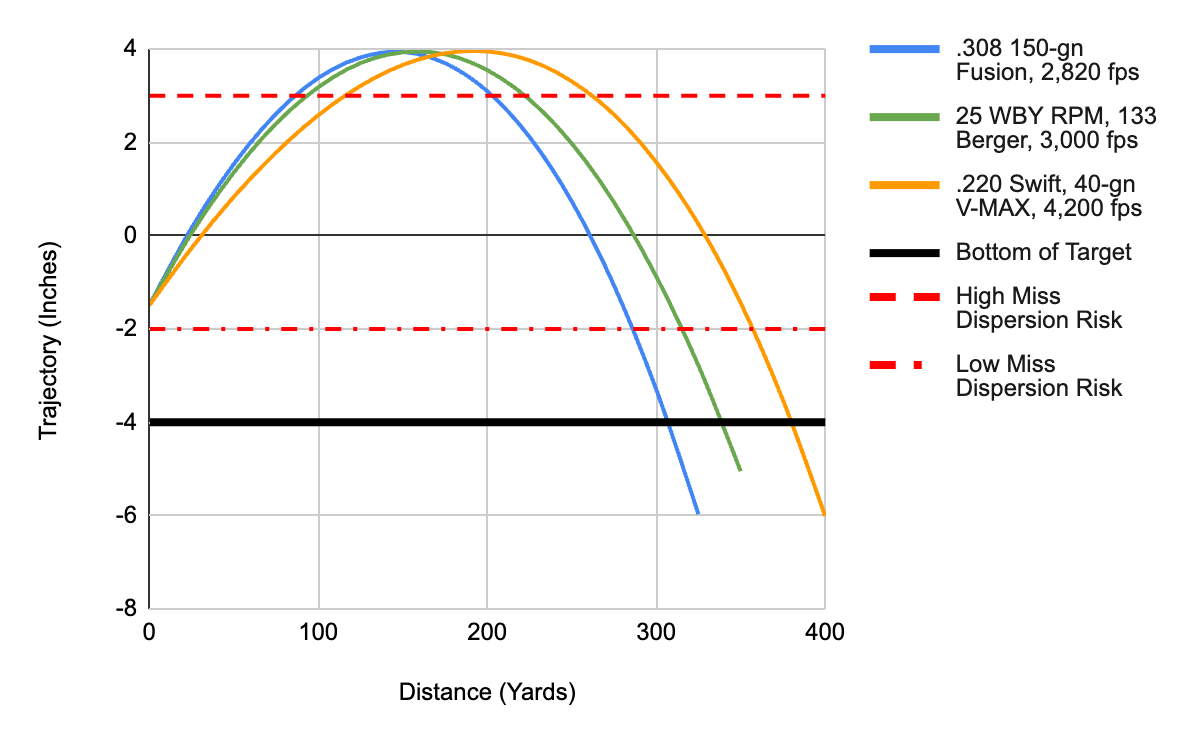

Seeing the gut-checking reduction in effective max-point-blank-range due to the unpleasant realities of dispersion, it begs the question: do flat-shooting cartridges even matter at these distances? Let’s take a look. We’ll consider the following loads simply on the merits of target impacts:

.220 Swift, 40-grain V-Max, 4,200 fps

- MPBR: 380 yards

- 1.25-MOA Precision Effective MPBR: about 355 yards

- 2-MOA Precision Effective MPBR: about 335 yards

- Between about 120 and 250 yards, upper trajectory will cause some high misses

25 WBY RPM, 133 Berger, 3,000 fps

- MPBR: 339

- 1.25-MOA Precision Effective MPBR: about 315 yards

- 2-MOA Precision Effective MPBR: about 300 yards

- Between about 130 and 240 yards, upper trajectory will cause some high misses

.308 Winchester, 150-grain Fusion, 2,820 fps

- MPBR: 307 yards

- 1.25-MOA Precision Effective MPBR: about 287 yards

- 2-MOA Precision Effective MPBR: about 275 yards

- Between about 90 and 200 yards, upper trajectory will cause some high misses

If we only calculate MPBR, there is a big difference between what we consider flat-shooting cartridges and ones we don’t. However, when taking into account the limitations of our rifle system and hunter precision, the difference isn’t nearly as decisive. In fact, cartridges with flatter trajectories can literally outrun their cone of fire. That means that because the trajectory is flatter, a larger portion of that is spent in space where a certain percentage of shots will miss the target. Notice the difference between theoretical MPBR and 2-MOA precision MPBR numbers:

- 220 Swift: 45 yards

- 25 WBY RPM: 39 yards

- 308 Win.: 32 yards

The flatter-shooting cartridges show a greater difference between calculated max-point-blank range and the effective MPBR considering 2-MOA of dispersion. Flatter cartridges do extend your effective MPBR, but not by as much as you may think. Another substantial miss factor occurs when we look at the peak of the trajectories.

The Upper End of the Curve

One phenomenon that is fascinating to look at is that dispersion affects our MPBR-based shot at shorter distances too, where our rifle system’s pattern of error overlaps the peak of the trajectory. In this zone, we will have a certain percentage of shots (up to 50 percent) miss high. As with the bottom end of the trajectory, flatter-shooter cartridges will actually spend more of their flight path in this zone than slower cartridges like the .308 load listed. This means that not only is our reliable MBPR reduced, but our high misses are increased for a greater range of distances. The lowly .308 load only will register high misses for around 100 yards of its flight path compared to 110 to 130 yards with the flatter-shooting options shown.

The Takeaway

Max-point-blank-range can still be used, and it’s a very valuable tool inside 300 yards. Shooters have certainly used it to score hits at longer MPBR distances, but the degree of certainty for a clean shot decreases dramatically, and inevitable misses increase, as the distance approaches your MPBR. Add in wind uncertainty, range uncertainty, and shooter error, and it becomes a poor choice.

Aim Small Miss Small

If MPBR-style of aiming were totally worthless, shooters would have scrapped it years ago. While a dial-up or hold-over method is significantly more precise at distances beyond 300 yards or so, you can still take advantage of the MPBR principle, but you need to make some adjustments. One simple practice is to aim precisely but favor low on closer shots that fall within the bullet’s peak trajectory. This will help you avoid missing high. At distances close to your MBPR, favor high, bringing your pattern of dispersion fully up onto target. This is a bit counterintuitive to the reason you might want to use MPBR, but it allows you to still hold on the animal to that distance.

Another option is to simply reduce your MPBR target size so that it’s smaller than the vital area of your quarry. This allows some forgiveness on those high or low misses and still provides you a solid MBPR to operate within. Using a 4- or 6-inch target for a deer would allow some of those inevitable misses to still strike the vitals.