A female woolly mammoth tusk unearthed in an area known to host ancient hunting camps has given scientists insight into how the biggest of all big game animals interacted with the humans subsisting off them, according to a new study published Wednesday in Science Advances. Many of the study’s conclusions are based on DNA from the tusk of one mammoth in particular.

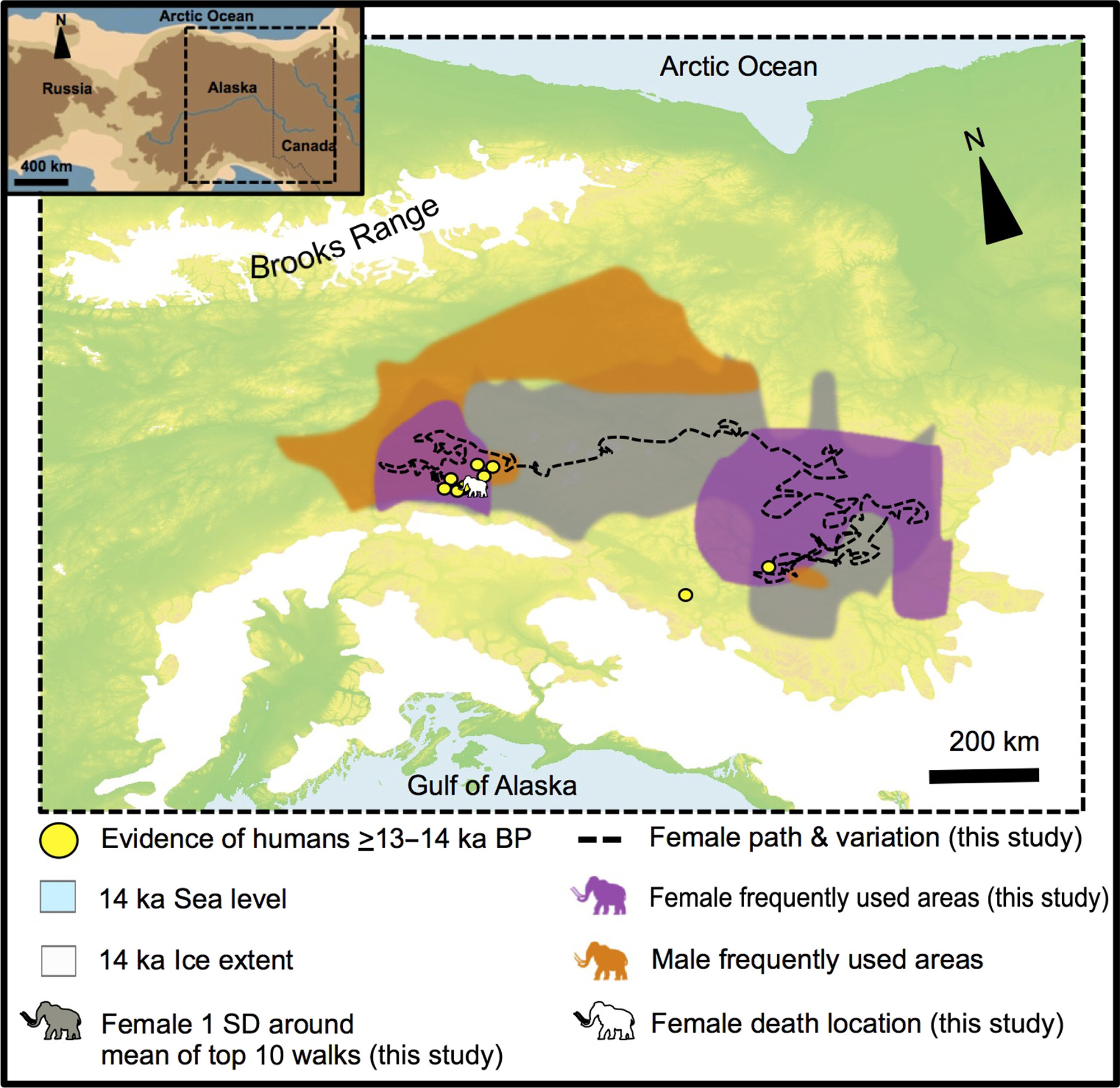

Humans and woolly mammoths interacted in modern mainland Alaska some 14,000 years ago, according to the study’s authors. Hunters and mammoths overlapped by about 1,000 years at the end of the last Ice Age, after which point mammoths went extinct. Humans had likely started moving east to cross the Bering Land Bridge even as the enormous mammals moved west into Alaska from northwestern Canada. Remnants from subsistence use of woolly mammoth carcasses have been discovered around the Swan Point Archaeological Site along the Tanana River, southeast of Fairbanks. The Swan Point site is also where researchers discovered the tusk that helped them retrace mammoth migratory routes.

The female whose tusk was discovered was related to a herd of other woolly mammoths who died in the same area, proving that the Swan Point site was high-density woolly mammoth habitat. Two distinct herds populated the region, a conclusion scientists made based on past research of hundreds of other mammoth carcass fragments. Isotope analysis of the tusk revealed that the female likely underwent a large relocation in the middle of her 20-year lifespan, at which point she moved from modern-day Canada into modern-day Alaska. Researchers were able to estimate the route she took based on the isotopes, or chemical makeup, of the tusk, which grew every day she was alive.

Illustration via University of Alaska Fairbanks

“She wandered around the densest region of archaeological sites in Alaska,” lead author and University of Alaska Fairbanks Ph.D. student Audrey Rowe told Phys.org. “It looks like these early people were establishing hunting camps in areas that were frequented by mammoths.”

She reached the end of her life after spending three years in interior Alaska. Another author on the study, Matthew Wooller, points out that the mammoth likely died at the hands of hunters.

“She was a young adult in the prime of life. Her isotopes showed she was not malnourished and that she died in the same season as the seasonal hunting camp at Swan Point where her tusk was found,” he told the outlet.

The people living in the area were likely ancestors to the Tanana Athabascan people, a semi-nomadic hunting, trapping, and fishing tribe of inland Alaska Natives.