STEPPING INTO THE BUS for the first time is a powerful experience. That’s not because I’m on a spiritual journey, or feeling the aura left by a man who slowly starved to death inside it. Yes, I’d read about Chris McCandless’s unfortunate demise and watched the movie. But I’ve heard more stories about this place from my dad and his brother. Watching them set foot inside their old hunting camp for the first time in 50 years is like seeing a piece of their history for myself. Although they last visited the bus when it was 40 miles in the bush outside Fairbanks, its new location at the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ engineering building doesn’t stop their memories from flooding back.

“Remember when Dad blew up the stove?” my dad asks my uncle. “That sure got everyone up!”

My dad is looking at the old woodstove, still in its place. It’s made from a 55-gallon drum — something that was common in camps and cabins at the time — with a simple stand, a door installed in one end, and a 6-inch stack jammed into a hole in the side. It made a fine stove, and my grandpa would get up in the mornings to get the fire going. According to my dad and uncle Jerry, Grandpa was a fan of petroleum products. Rather than carefully building a nest of tinder and kindling to send a stream of smoke slowly wafting through the sheet-metal chimney, he sloshed a bit of gasoline into the stove. I’m not sure if he lit it or if it was ignited by a half-dormant coal in the bottom of the stove, but I am sure the gasoline was a mistake. With a loud bang, the stove door blew open and the stack lifted away from its hole in the stove. It woke everyone sleeping in their cots and filled the bus with smoke.

I’ve heard the story many times, but opening the stove door for myself makes it real.

Where Did the Bus Come From?

In 2020, a helicopter lifted Fairbanks City Transit Bus No. 142 out of the bush and it was brought about 100 miles back here to Fairbanks. For nearly 30 years, the now-infamous bus had been a magnet for tourists and soul-seekers, many of whom were unprepared to deal with the hazards at the edge of Alaska’s wilderness. People had to be rescued each year, and some even died trying to reach (or return from) the bus.

The attention that the bus received was almost entirely due to the tragedy of Chris McCandless, whose story was publicized in the 1997 nonfiction book, “Into the Wild,” which was also made into a film in 2007. Fairbanks, Alaska, is an “end-of-the-road” sort of town, and like many others, McCandless ended up here in early 1992. He wanted to live off the land but sadly was grossly unprepared and breathed his last inside Bus 142.

One of the most common mysteries around the bus is how the hell it got out there in the first place. Even most Alaskans just know that it was there — but not how it got there or who brought it all those miles into the bush. The answer is one of many things we’re learning about the bus in the wake of its removal.

Angela Linn, the senior collections manager for ethnology and history at the University of Alaska’s Museum of the North in Fairbanks, knows exactly how it got there. She’s been doing research on the bus, which includes setting up interviews with folks who used the bus long before McCandless found it in 1992.

“Bus 142 was part of a group of four buses that were used to house members of the Yutan Construction Company crew who were working on improving the Stampede Trail in 1961,” Linn told me. “The state had funding to allow the road commission to make improvements in areas that contributed to the economic infrastructure. Jess Mariner was a heavy equipment mechanic for the YCC and he personally bought two buses to house his family during the project. Bus 142 was where they slept, and the second bus was their living space. The construction company also bought two buses for the rest of the crew to sleep in.”

The driver-side front wheel of Bus 142 became damaged during the project, says Linn. Knowing folks would use it for shelter along the Stampede Trail, Mariner pulled the bus to the side of the trail and left it.

People often play up the fragility of the North’s ground and climate, but the wilderness also has a way of swallowing up the evidence of our presence. In much of Alaska, where there were once networks of trails and cabins, the land looks untouched. I’ve been hiking up spruce and alder-choked creeks and come across dump trucks from the early 1900s, parked more than 50 miles from the nearest road. Even entire towns, like the 1,500-resident town of Richardson, have been wiped from Alaska’s landscape, with little sign that they were ever there. And before those, there were untold Native villages, camps, and travelways that have been swallowed by the wilderness.

The Freel Hunting Camp

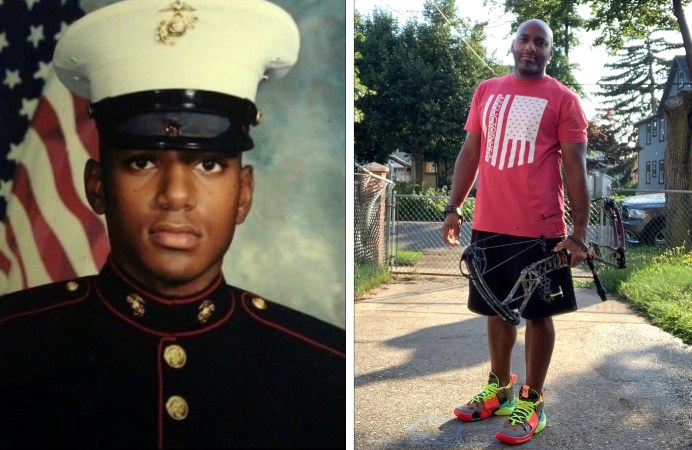

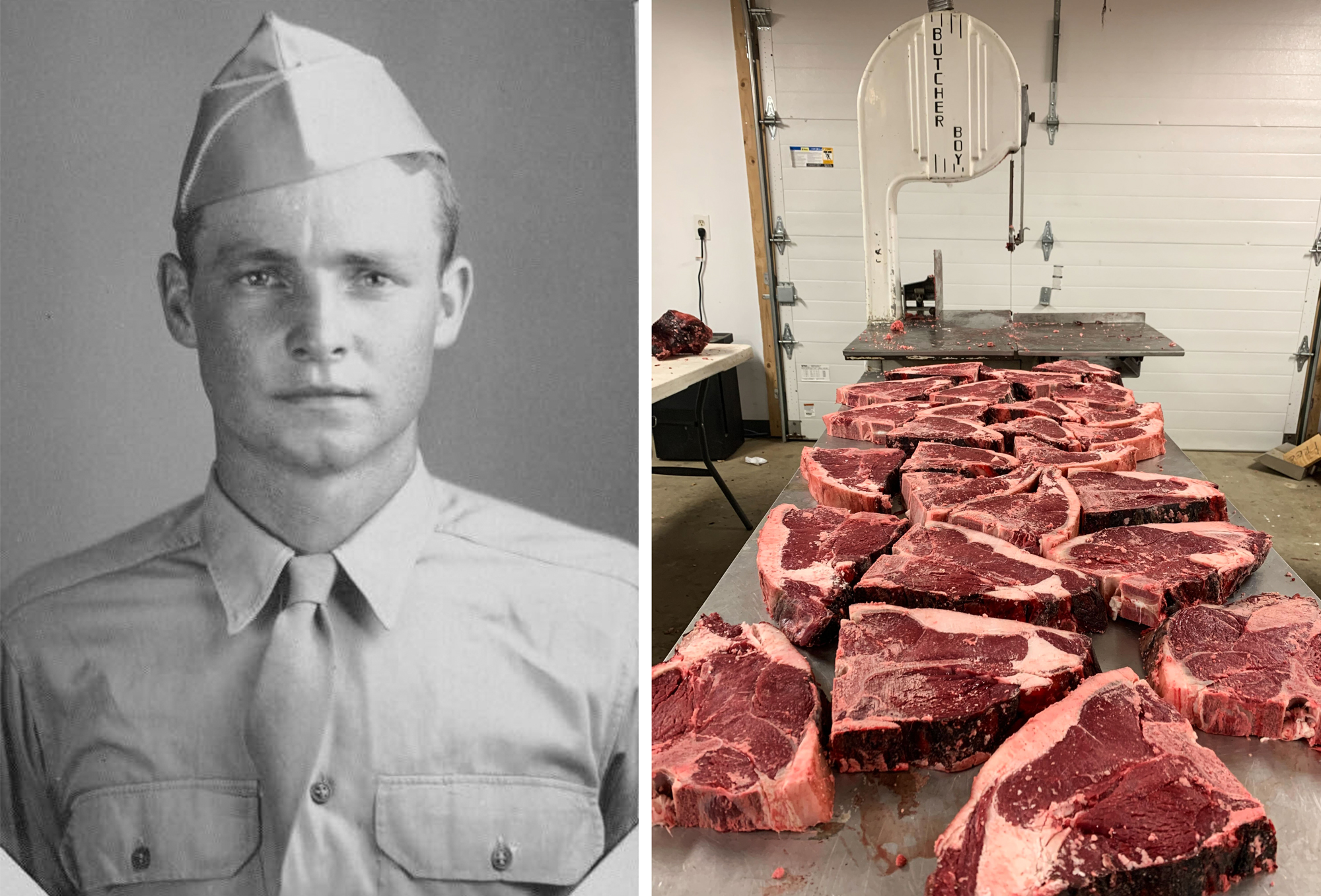

For my family, the story of the bus really begins with the story of my grandpa, Jearold “Jed” Freel. He was a paratrooper in the 82nd Airborne division in World War II who hit a stroke of luck shortly after the war officially ended. The soldiers had received their back-pay while still in Germany, and Grandpa Jed got into a big poker game — and started cleaning up. Fearing the guys were going to kill him to get their money back, he casually filled his pockets and helmet with cash, left a pile on the table (to distract them for a bit), went to the bathroom, and climbed out the window. The cash he could carry totaled roughly $10,000. That’s what he used to move to Alaska, where he became a mechanical insulator.

My grandpa was a meat hunter’s meat hunter. If he got one moose, that was good. But if he got three or four, that was even better. Times were a bit different then, and hunting moose and caribou was a family and neighborhood affair. His family had a big meat shed and the equipment to deal with piles and piles of moose meat. Family friend Duane Spellecacy (the kid with glasses in the home videos), who came along on many hunting trips, told me that his dad had the big meat grinder, and my grandpa had the steak cuber and bandsaw. I still use that bandsaw to cut my own moose and caribou.

After hunting in the 40-mile and Steese country (the rolling hill country between Fairbanks and the Canadian border to the northeast) for several years, things were getting too crowded for Grandpa. Around 1965, he heard about a bus with bunks and a woodstove that had been hauled out on the Stampede Trail. This was before the Parks Highway was punched through to Anchorage, so there weren’t too many other hunters in that area in those days.

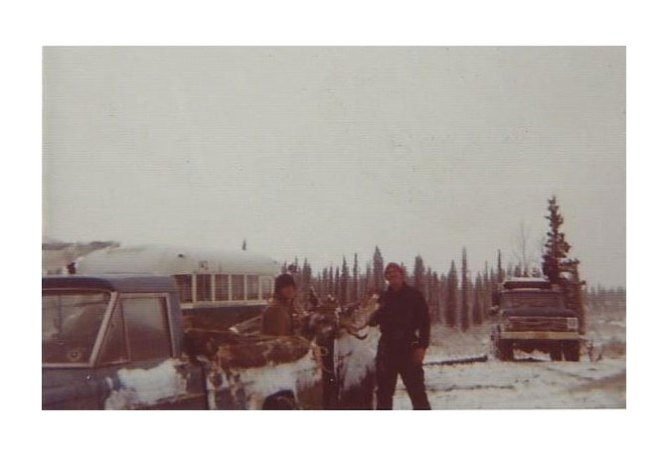

Like they hunted everywhere else, the Freel family and their friends loaded their pickups with gear, food, handyman jacks and planks, and drove out to the bus. Some of the places they took pickup trucks in the 1950s and 60s would blow the minds of even today’s UTV drivers and cast shame upon all those lifted Toyota Tacomas with traction boards and gear racks that will never be taken off the blacktop.

My dad, Britt Freel, was young when they made those trips out to Bus 142, and he tells me that he mainly remembers flashes. (He’s the little blonde kid in the home videos.) He remembers killing his first moose out of that camp in 1969, when he was 10 years old. My dad, his dad, and a few other hunters were sitting up on a hill watching a bull moose work through a flat. Grandpa Jed told him to go kill that moose, so my dad and a couple other kids worked their way down the hill to set up for a shot.

“I remember shooting that bull, sitting there resting the rifle on my knee,” my dad tells me. “It was a Remington semi-auto .30/06. Then Dad came down and we all cut it up and hauled it back to camp.”

“There was one time I remember in 1969 that the water level in this creek down below the bus was dropping and it created a drying, landlocked pool that had a bunch of grayling in it. We didn’t have a fishing pole, so one of the guys shot into it with his .300 H&H, shocking the fish so they were easy to grab. That was dinner for the night.”

My uncle Jerry has told me a story several times over the years — about a cow moose he shot on a hunting trip to the bus that ran, then swam, right into the middle of a small lake and died. (I’m pretty sure this is the moose head he picks up around the 2-minute mark in the video.) He was excited about killing the moose until his buddy said, “Oh no, what the hell is your dad gonna say?” My grandpa would never shoot a moose he couldn’t back the truck up to, and my uncle Jerry started worrying himself sick. Luckily, one of the vehicles had a winch, and someone pulled the rope out and hooked it to the moose.

When I shot my first bull (accompanied by both my dad and uncle Jerry), the moose fell into hip-deep water. I remember this part very distinctly: As he was kicking his last, splashing water into the air, my uncle looked at my dad and said, “You know what our dad would say to us right about now?”

The Legacy — and Future — of Bus 142

“Remember, Britt, there used to be bunks along this side and back here?” my uncle Jerry asks my dad as we look around the bus now. “And we used to hang our wet clothes from these handrails to dry out.”

Even though the bus is back inside city limits, standing inside it brought plenty of memories back to my dad and uncle. More flashes of memory came back to them as they walked around it. Listening to my dad and uncle recall them gave me a glimpse into some of their last good times with their dad in the late 1960s, before he suddenly passed away in 1971. By the time I was born, in 1985, my family had abandoned the camp. My grandma moved my dad and most of his siblings back to Colorado where she was born, and after my uncle Jerry returned to hunt there once in 1972, they never used it again.

Read Next: The Top Moose Cartridges

At one point in the visit, my dad mentioned that he thought someone had recorded home videos at the bus on some of their trips. That thought spurred a search that turned up a box of my grandma’s 8mm films. When I digitized the films this month, I discovered footage from two of their trips to the bus, in 1966 and 1968. No one had watched those old films in years.

Since its removal from its long-resting location in the foothills of the Alaska Range, Bus 142 has been awaiting repair, preservation, and hopefully, one day, exhibition at the university’s Museum of the North. To airlift the bus, holes had been cut in its roof and floor to secure cables to the frame, and they need fixing. The number 142 has been shot out and pocked with bullet holes, many of the glass panes are gone, and the rotten floor is temporarily covered with plywood so we can safely walk inside.

Fortunately, the Museum received a $500,000 grant for the conservation work on the bus and historians and curators like Linn are busy cataloging everything that is inside, or written on, the bus. Funding for the actual exhibit is still in progress, and Linn says museum staff still needs to raise $77,000. (The team is applying for grants, but donations can be made here.)

The bus was made famous because of Chris McCandless, but this project and its eventual exhibition will acknowledge much more than his chapter in the bus’ long history. The full scope of the project includes an acknowledgement of the area’s rich indigenous past, the settling of interior Alaska, knowledge of Alaska’s wilderness and the pop-culture mythology around it, and rites of passage and the spiritual journeys that some pursue into Alaska. And finally, it will create a place where visitors like my family can come relive, and share, some of their own stories.

The museum is seeking input, stories, photos, and film from those who have experiences with the bus before 1992 or in the area before the Stampede Trail. They have documented my dad and uncle’s stories, and they’ve gathered other film footage from the bus too. They also want to hear from people who may have strong feelings one way or another about removal of the bus. If you have something to share, you can contact them here.

I’ve written before that I think removing the bus was a good thing, and I still do. After McCandless’ death, it became a literal tourist trap, vandalized with graffiti and bullet holes. By the time the bus was removed, it had changed into something that no longer resembled a hunting camp. Those moments are preserved on a few feet of 8mm film, and in my dad and uncle’s memories. And someday, when I bring my kids over to the museum to look at Bus 142, it won’t be to tell them the story that ultimately resulted in Bus 142’s removal. It will be my grandpa’s hunting stories, and their grandpa’s hunting stories, and all the happy times they had there.

This story first ran on Nov. 23, 2022.