My son John Hunter Bannon Snow is known to one and all as Jack. I’ve written about Jack before. And his love of fishing, shooting, and hunting brings joy to this gun writer’s heart.

Though Hunter is a popular name these days—where I live in Montana you can’t swing a prairie dog without smacking a “Hunter,” “Bridger,” “Kody,” or “Maverick” in the chops—bestowing that name upon Jack had nothing to do with chasing deer, Western living, or the outdoors.

Hunter is a family name that dates from 1944. My father is John Hunter Fox. His father, my grandfather Philip Fox, named him in honor of his best friend, John Charles Hunter. (How I became a Snow, rather than Fox, is a tale for another day.)

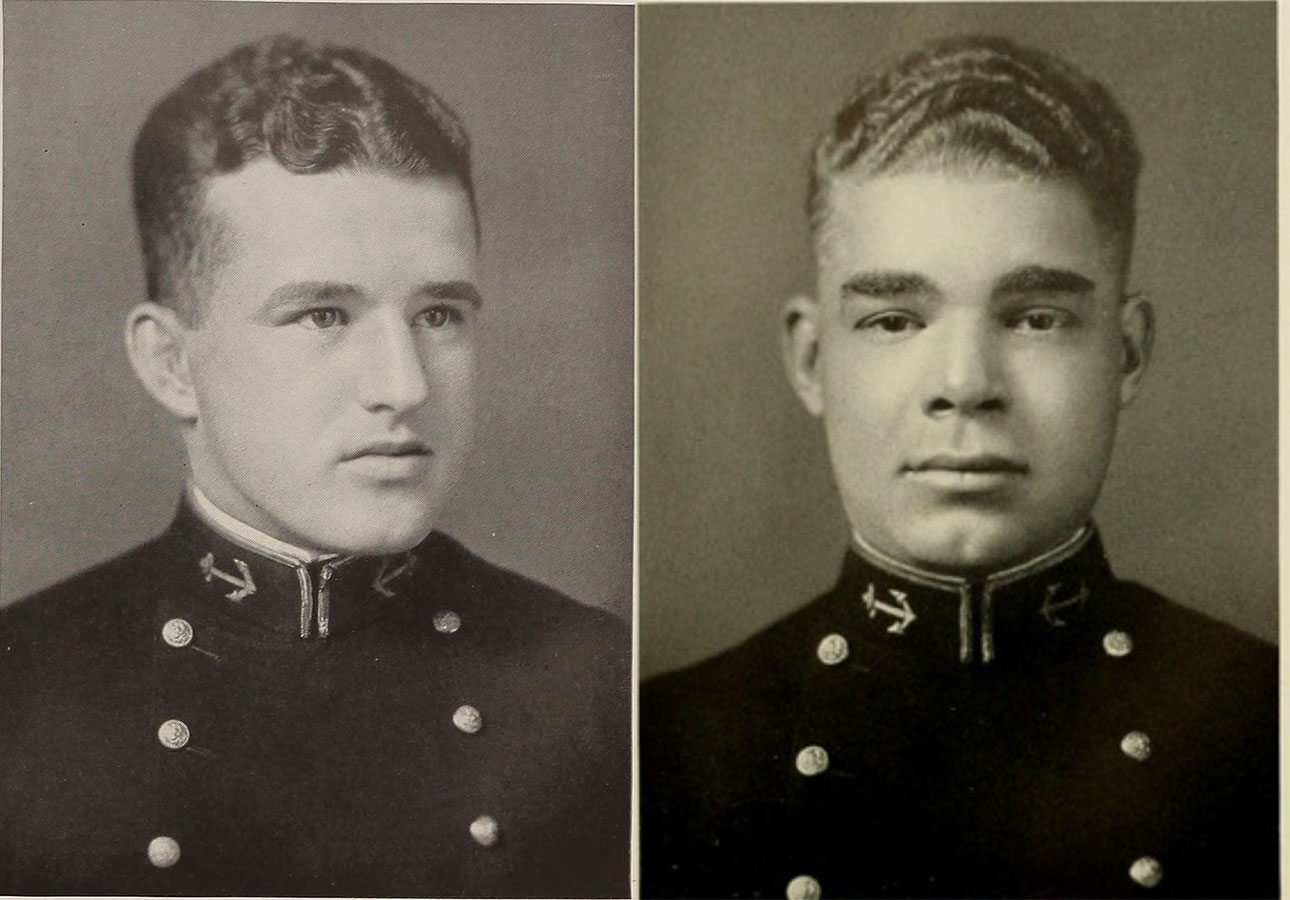

My grandfather met John Hunter, who was also known as Jack, at Annapolis where they were midshipmen together at the United States Naval Academy. They were both from Philadelphia and that shared background is part of what brought them together. They played sports together—Jack Hunter was a stand-out wrestler for the Blue and Gold—and became close during their years at the academy.

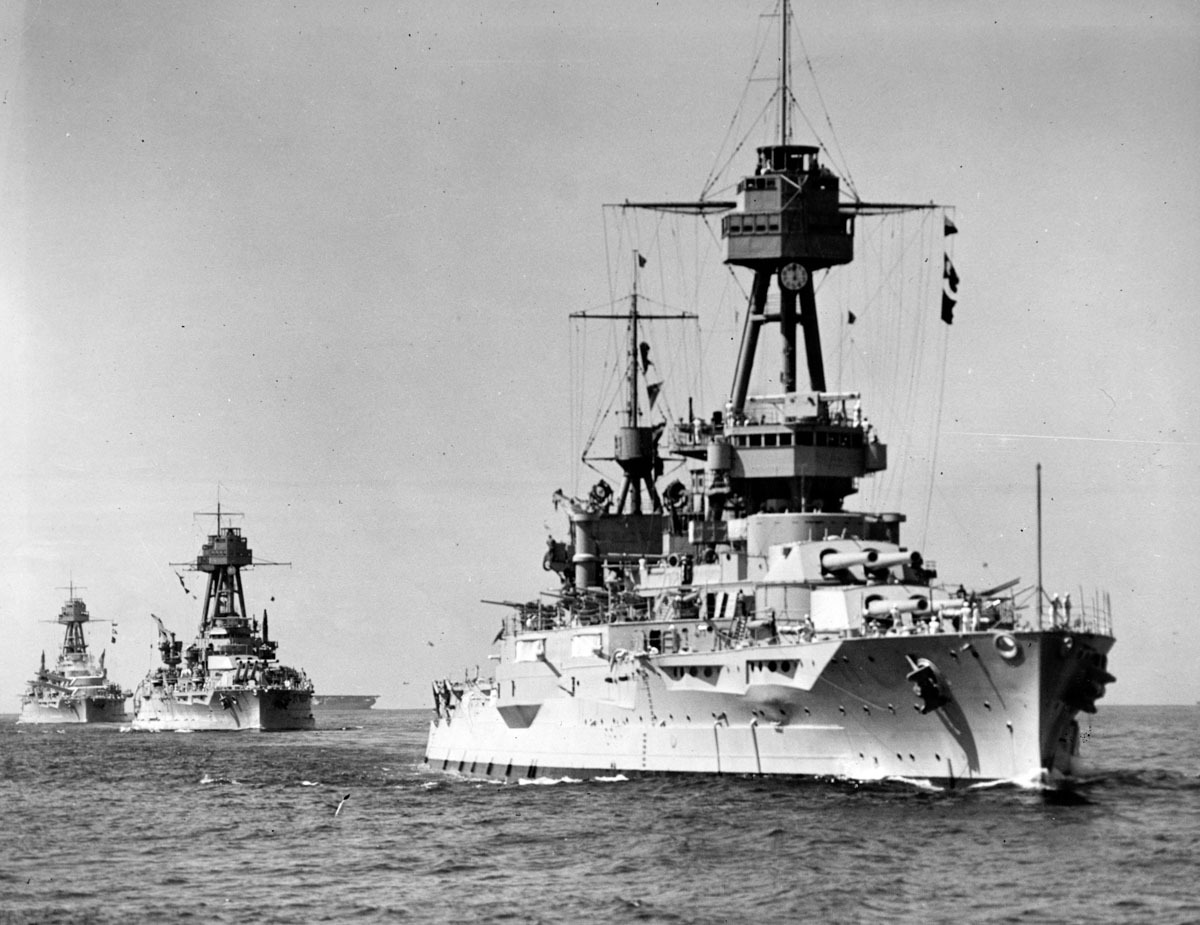

Upon graduation in 1936, they went their separate ways. My grandfather’s first assignment was aboard the USS Pennsylvania, while “Pappy” Jack Hunter went to the USS New York. Both those venerable battleships carried 14-inch guns and were commissioned just prior to the First World War.

The Naval Academy class of 1936 entered service at about the worst time imaginable. The careers of those young Ensigns intersected with World War Two with devasting results. Few graduating classes in the Naval Academy’s history suffered a higher casualty rate.

Jack Hunter was one of them.

Following his stint on the New York, Hunter served on the USS Louisville and then in October 1939, he was promoted to Lieutenant JG and went to Naval Air Station Pensacola in Florida to learn to fly. In June the following year he reported aboard the USS Lexington (CV-2).

He flew in the Lexington’s Scouting Squadron, piloting a Dauntless SBD-3 dive bomber. Like Hunter, the Dauntless was new to Naval aviation. Its first official flights occured in May of 1940, just a few weeks before Hunter got behind the yoke of his own SBD.

The Dauntless was the Navy’s main carrier-based Scout/Dive Bomber during World War Two. While SBD stood for “scout bomber Douglass” it also earned the plane it’s nickname: slow but deadly. During the war the Dauntless sent more enemy ships to the bottom of the Pacific than any other allied aircraft.

On December 5, 1941, two days prior to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Lexington was in route to Midway to deliver Vindicator dive bombers to Marine Scouting Squadron 231. In the immediate aftermath of December 7, 1941, the “Day of Infamy,” the Lexington was ordered to turn around for Pearl Harbor as fast as possible. Her mission was to find and destroy the Japanese fleet that had attacked Hawaii.

The next morning, Wednesday, December 8, Hunter went on patrol in search of the enemy as the carrier steamed south-southeast toward Pearl. His airplane developed engine trouble about 175 miles from the Lexington and 125 miles from the nearest ship, and he and his radioman made a forced landing in the rough seas a little after 8 a.m. Another Dauntless pilot on the patrol saw Hunter and the radioman, Earl W. Lang, exit the aircraft uninjured and climb into their small rubber life raft.

Fuel running low, that pilot eventually returned to the ship. Because of the extraordinary circumstances of being thrust into war, the Lexington couldn’t divert its path and an immediate rescue attempt was impossible. Around 3 o’clock in the afternoon the USS Drayton, a destroyer assigned to the Lexington’s task force, and several airplanes arrived in the area where Hunter and Lang splashed down. They searched for the rest of the day, and through the night. At noon on the following day, the rescue attempt was called off.

Per naval custom, they were declared dead a year to the day following the unsuccessful search, December 9, 1942, having been listed as “missing” for the 12 months prior. When my father was born June 28, 1944, at the Charlestown Navy Shipyard outside Boston, Lieutenant Fox named him for his best friend.

I think about Pappy Jack Hunter every Memorial Day, and at other times too. I try to imagine myself in that young man’s position, in a raft in the vast empty expanse of the Pacific. How long were he and Lang able to endure that pitiless sea? Did they ever catch a glimpse of a distant ship or hear the drone of the engine from the plane of one of their fellow naval aviators? Or was their isolation complete after their wingman was forced to fly away?

I like to think they took some comfort in each other’s company, but there’s no way their end came without being awash in horror.

In the tally of the U.S. Navy’s dead, Hunter is listed as an “operational loss,” an antiseptic term used for accidents and other deaths not directly related to combat. That’s how most aviation casualties in World War Two occurred. Dogfights and anti-aircraft batteries are the dangers we imagine pilots confronting, but the mundane reality is that engine failures, equipment malfunctions and training accidents are what claimed most aviators. Among Hunter’s and Fox’s class of ’36 shipmates, ten other men were aviators whose deaths were “operational losses.” Four others were pilots killed in action.

My son is now the age that Jack Hunter was when he entered the Naval Academy. I can’t look at my Jack—full of the hopes, dreams and fears that every young person has, bursting with ideals and ambitions, a naturally curious and gentle soul—without imagining his namesake as well. How much they would have had in common, I can’t say. But like my Jack, Jack Hunter was affable, widely liked by his classmates, and had a love of wrestling and football. Were they to meet, I like to think they’d have been friends.

In the late 1930s the winds of war were stirring, but I doubt that any member of the U.S. Naval Academy class of 1936 could have foreseen the scope and nature of the conflagration that engulfed the globe. Nonetheless, those young men rose to the challenge and helped rescue the world from tyranny and oppression, many of them paying for that triumph with their lives.

Over the years, countless men and women have done the same, raising their hands and swearing an oath to protect us, come what may. For them, and for all their sacrifices I am grateful.

We can never repay the debt we owe them. Even our ability to honor them has its limits. But we can remember them. And as long as they are remembered, whether in old photos, shared stories, or even in a family name, a part of them, and knowledge of the deeds they accomplished, lives on forever.