Photo by Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody Wyoming, U.S.A./ Jack Richard Collection

American hunters are proud of saying that we brought back the nation’s wildlife species from the brink of extinction. Most of the animals we love to hunt—whitetails, wild turkeys, elk—were recovered because our hunting licenses funded professional management and we agreed to restrain ourselves through bag limits and season structures.

But one species—America’s bison—took a different path to recovery, and the current struggle over where to continue the restoration goes back to decisions made at the dawn of the nation’s wildlife conservation movement.

Bison was the species that jump-started that movement. Back in the 1880s, just two decades after visitors to the West described limitless herds of the animals, it appeared that bison would be exterminated from the planet. Hide hunters slaughtered them, railroads and homesteads fragmented their range, and soldiers killed them to deprive warring Indian tribes of their main food source.

By some estimates, the number of bison plummeted from a population of between 30 and 60 million in 1800 to fewer than 1,100 in 1890.

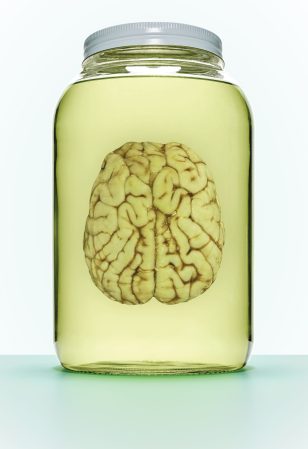

Leaders of the nascent conservation movement—Theodore Roosevelt, William Hornaday, and J.A. McGuire (founder of Outdoor Life) among them—concluded that the way to save America’s buffalo was to round them up and protect them in zoos. Only by creating a captive population of breeding bison would the species be saved, these early conservationists determined.

The few remnant wild bison outside of Yellowstone National Park were corralled at the Bronx Zoo in New York City—the model for the U.S. Mint’s iconic buffalo nickel, “Black Diamond,” was one of these captives—and the offspring of these survivors were sent to other zoos around the country. Over generations, these bison lost their wildness, and their genes became diluted as they were interbred with cattle, first at zoos and later on the private livestock ranches where surplus bison were shipped.

Conservationists—including members of the American Bison Society, founded in 1905 by Theodore Roosevelt—call bison the “left-behind” species because of that decision to institutionalize them rather than work to return them to functional landscapes.

With a few exceptions, the source of many of the nation’s private bison herds is the offspring of these captive animals, which became more domesticated with each generation. That helps explain why, in many states, bison are considered livestock. And it helps explain why the pure bloodline and the relatively wild nature of Yellowstone Park’s bison are so valuable to those who would repopulate the plains with this icon of the American West.