Back in 1982, then-Secretary of the Interior James G. Watt caused a teapot tempest when he unveiled a new design for the seal of the Department of the Interior.

The DOI’s signature bison, intended to represent the rugged landscape and wild species that fall under management of the department, was flipped from facing left, as it had for the previous 133 years, to facing right, in keeping with Watt’s conservative politics.

Symbols being what they are, Watt’s move was widely perceived as a statement that he intended to move the department away from the pro-environment policies that had defined it in the post-ecology movement of the 1960s and ‘70s, and toward development and extractive uses of public lands.

A native of rural Wyoming and outspoken champion of industry and deregulation, as Interior secretary Watt was reluctant to protect imperiled plants and animals under the federal Endangered Species Act, eager to open wilderness areas to energy leasing, and vocal in his disdain for the Land and Water Conservation Fund.

The head of the bureaucracy that manages most of America’s federal lands and so many other programs that it’s been called “The Department of Everything Else,” the Secretary of the Interior has wide latitude to move the nation’s natural-resource policy one way or the other. To the left, or to the right, as it were. Watt’s successors, including Bruce Babbitt, President Clinton’s choice to lead the department, and Sally Jewell, who served under Barack Obama, undid many of his Reagan-era policies and instituted more preservationist, protectionist policies.

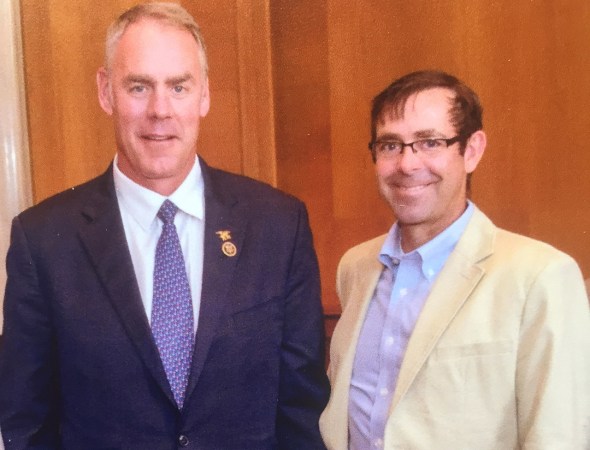

That sort of wide-swing tremolo has been hard on America’s wild critters and public lands, which may help explain why Ryan Zinke was a welcome surprise as President Trump’s pick to lead Interior. Zinke, the son of a plumber in Whitefish, Mont., had risen to prominence in Montana politics as a moderate Republican. He won the state’s lone congressional seat by running as a pragmatic centrist. As Interior secretary, his champions thought, Zinke might be a counterbalance to Trump’s impulsive brand of pay-back politics.

Western conservationists hailed Zinke as a confirmed hunter and angler who recognized both the economic and ecological benefits of healthy, accessible public lands. Industry insiders welcomed him as a secretary who might restore consistency and predictability to land-management policy. And Washington taste-makers saw Zinke, a former war hero and collegiate football star, as a rising Republican who might ascend within this administration or the next.

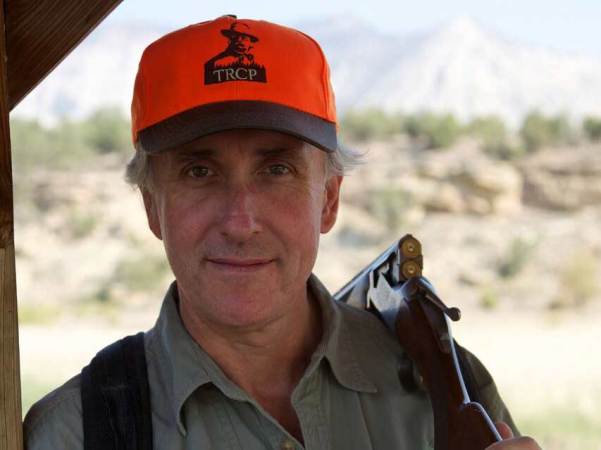

Zinke liked to compare himself to Teddy Roosevelt, and his acolytes were all too eager to amplify parallels to TR as a fellow conservative, soldier, conservationist, and rawboned advocate for the “strenuous life.”

Zinke, 57, announced over the weekend that he would step down as Secretary of the Interior on Dec. 31, less than two years into a tenure that was defined by policies that benefitted hunters as well as energy extractors, the removal of protections from large expanses of public land, big ideas that fizzled, and chronic accusations of ethical lapses.

Some of the arrows that took down Zinke are pretty flimsy, and his tenure as Secretary of the Interior shouldn’t be defined by the ethics investigations that may be his undoing in politics. Instead, his failure to leave a Rooseveltian legacy stems from underdeveloped understanding of the department, lack of a coherent political philosophy, a vacuous image-first personality, and an unhealthy thirst to join the ranks of the wealthy industrialists who sought to influence him and his policies.

All Hat, No Teddy

Much has been made of Zinke’s first day on the job, during which he rode a horse to work following the inauguration. It was showy, brash, and entirely without substance. Like Watt’s view-switching bison, it was a gesture that was supposed to tell the world that a real cowboy was in charge at Interior.

The next day, hunters and anglers got a gift with Zinke’s secretarial order that ensured recreational access to millions of acres of federal lands and waters. Later that day, Zinke overturned a ban on lead ammunition and fishing tackle on Interior-managed land (the ban, a gift to radical environmentalists, had been imposed on the very last day of the Obama administration). He also instructed federal land managers to identify areas where outdoor recreation could be expanded. A quarter million acres of national wildlife refuges opened to hunting and fishing by that single action.

So far, so good. Those secretarial orders suggested that sportsmen might get preference in multiple-use management of public lands.

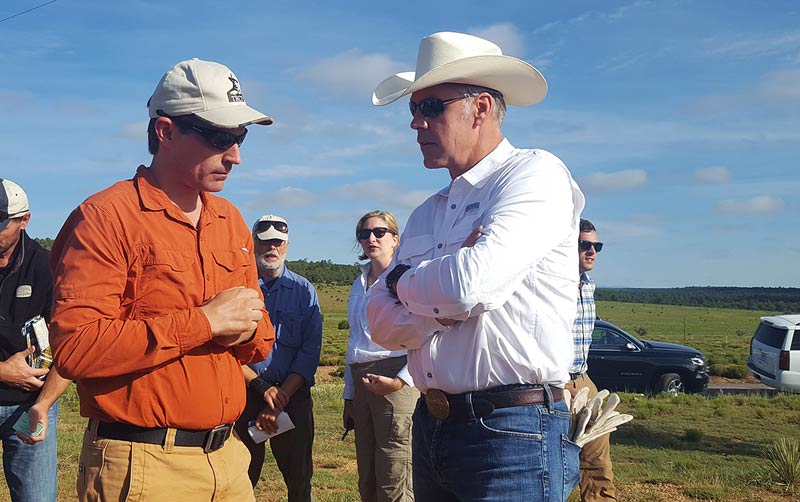

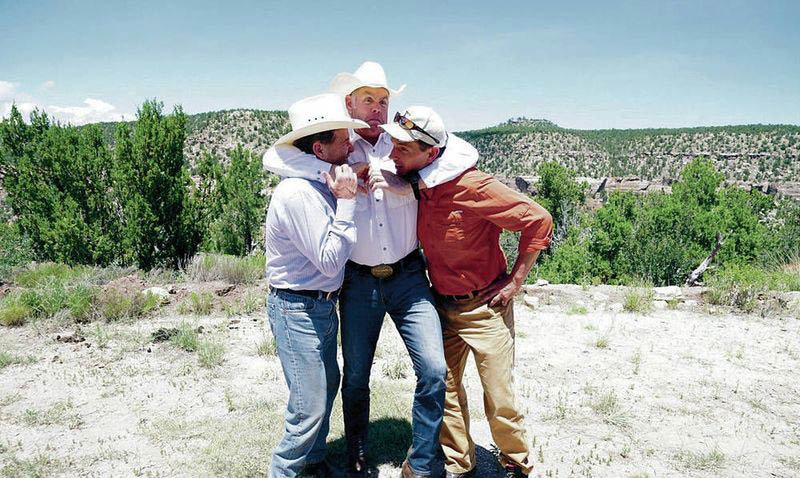

If there was an early indication of Zinke’s narcissism, it was during his first few months on the job, when he rode horseback through New Mexico’s Sabinoso Wilderness, along with New Mexico’s two Democratic Senators, Martin Heinrich and Tom Udall. Zinke had originally questioned the purpose of adding more land to the public domain, but then toured the wilderness, which was made publicly accessible with a key land trade that he first opposed, then supported.

Zinke wasn’t able to walk from the parking area down to the staging area for the horses, someone on hand for the event told me, because the tread on his cowboy boots was too slick for the steep slope. Using borrowed boots, he navigated the incline, then switched back into his cowboy boots for the tour and staged photos that appeared later on Instagram.

Two months later, Zinke shocked the conservation community when he released results of a Trump-ordered review of America’s national monuments. The Secretary of the Interior recommended huge cuts in two Obama-era monuments in Utah: Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears. Suddenly, any comparison to Teddy Roosevelt seemed strained.

Zinke’s legacy is likely to be forever tied to the reduction in monuments. The cuts were considered unforgivable by backcountry and preservationist groups, even though some of his other public-land priorities, including elevating the management status of wildlands surrounding national parks and prioritizing the protection of critical winter range and big-game migration corridors, have plenty of appeal for wilderness advocates.

Policy Vacillation

Over the last half-century, Interior secretaries have tended to fall into two types: administrators and activists. Watt, whose conservative politics defined his actions, is an example of the latter. The tenure of Ken Salazar, Obama’s first Interior secretary, could be characterized as improving processes and administrative performance of 70,000 employees of the department.

But Zinke defied definition, largely because of his lack of a righteous rudder, or any coherent political philosophy. When he tried to be a far-sighted administrator, proposing to decentralize the department and reconfigure regions based on watershed boundaries instead of state lines, even conservative Western governors balked because it might diminish their authority. At the same time, a sizeable bloc of career Interior employees started an insurrection and a well-organized whisper campaign to impugn their boss. One 30-year Interior employee told me that morale in the department was as low under Zinke as at any time in her career.

When employees went public with their discontent, they were often met with a Trumpian response: either quit or be reassigned to areas well out of their experience or expertise.

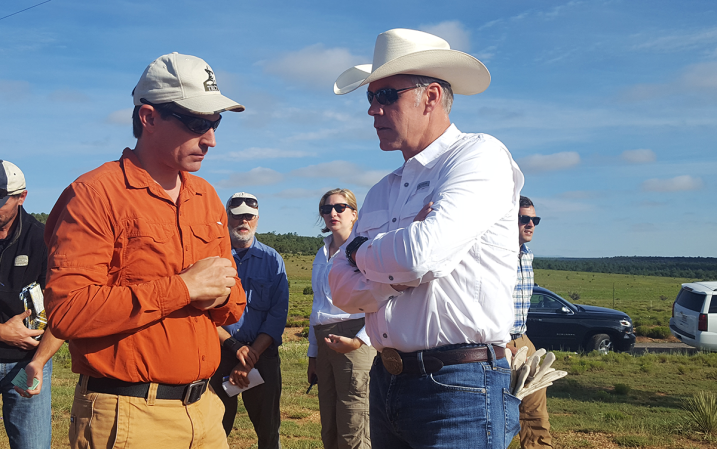

Was Zinke a sportsman-friendly advocate, who expanded access, or an agent of the oil and gas lobby, aggressively pushing for industrialization of our public lands in pursuit of a policy of “energy independence” despite the fact that an oil surplus was suppressing prices? Was he a conservationist, elevating the priority of critical wildlife habitat? Or was he an industry toad, proposing to erode protections of sage grouse, a perennial candidate for Endangered Species listing?

You could make a case for either side, which is part of Zinke’s problem. He might be anything to anyone, depending on the day and the issue.

Yearning for Wealth

Zinke’s hometown, Whitefish, Mont., started life as a big clearing in the Western woods. Originally called “Stumptown” for all the felled trees, Whitefish was a rough-and-tumble logging and railroad town. But over the last two decades, as vacation homes have gone up and boutique gift stores have replaced more earthy establishments in its business district, ski-weekend glitterati are defining its economy and culture.

The Zinkes, Ryan and Lola, have a modest house not far from downtown. They’ve turned it into a bed-and-breakfast, Zinke told me on a tour of his home, because they’re away so frequently. The home has a big yard. One of the ethics investigations that reportedly undid Zinke was an agreement with the developer of a hotel complex in downtown Whitefish that needed additional off-site parking in order to win approval from the local development council. The Zinkes reportedly allowed their yard to be considered for parking. The developer is the chairman of Halliburton, the multi-national energy company that stands to gain handsomely from Zinke’s relaxation of rules governing energy development on Interior Department lands.

That’s an oversimplification of the ethics complaints, but it hardly seems like it qualifies as a conspiracy to trade influence for income. Still, Zinke’s failure to see that the arrangement might raise eyebrows shows his lack of political sophistication. That same clumsiness defines his other ethical lapses: straining the rules on travel, his eagerness to meet with oil and gas lobbyists but not conservation groups.

Zinke is proud of his working-man roots and his route to success: high-school and then college football star, a Navy career that culminated in SEAL Team command. But it also seems that he longs to be admitted to the penthouse and seated with power brokers who serve on corporate boards and fly in private jets. His willingness to hobnob with influencers rather than commoners defined much of his daily schedule, and is a theme that threads through the 17 ethics complaints under investigation.

Read Next: Zinke’s World View

Interior and Beyond

National media outlets have reported that congressional ethics investigators intend to continue their scrutiny of Zinke, even after he leaves the administration. Where he’ll go is anyone’s guess, but a number of Montanans have suggested that if he skates through his legal trouble, he may come home to prepare a run for the governor’s office in 2020 or beyond.

A more immediate question is who will take Zinke’s office in Interior. The name that’s most frequently discussed is the current deputy secretary, David Bernhardt, a Colorado native and former energy industry lobbyist who served as Interior Department solicitor in the George W. Bush administration. His critics are quick to point out that one of Bernhardt’s clients in the private sector was Halliburton. Another, Samson Resources, is the largest privately held natural gas company in the U.S.

Politically, Bernhardt appears to be following the footsteps of James Watt, he of the right-facing bison. Watt, it should be noted, was convicted 10 years after leaving Interior on felony perjury and obstruction of justice charges based on an investigation into influence peddling.